Thematic Dissonance: No Wrong Notes!

by Antonio J. García

|

Antonio García teaching and performing at the Conn Selmer Institute (Indiana). |

Hear a 12-minute audio recording where I teach this concept to music educators using several of the notated examples below!

Young improvisers fear mistakes, the accidental dissonances as they solo. This is not surprising, as American musical education generally teaches consonance first and thoroughly so, leaving dissonance more a mystery. And yet a soloist’s identity or “sound” might well be determined more by how he or she treats dissonance in a solo: who wants to hear an entirely consonant composition, written or improvised?

I propose that before we clutter the minds of students with “left-brain” theory, chord/scale relationships, and patterns (all of which tend to encourage a frustrating, “cut-and-paste” sound in a soloist), we instead introduce them to the “right-brain” creative stimuli of tension and release, theme and variation, melodic contour, pace, lyricism, and yes, dissonance. By proving at the outset the strength of improvising thematically, we can greatly reduce students’ fear of soloing and provide for them the proper internal creative framework on which to apply the external theory that will follow in later study. After all, aren’t we teaching spontaneous composition?

Making “Wrong” Notes “Right”

First, let’s PROVE that there are no “wrong” notes. (What could lower a player’s fears more than that?) In the first class or clinic session, I demonstrate this using four sequential exercises, three of which everyone does simultaneously to save time and lower inhibitions. Each exercise limits the parameters of an individual’s choices such that dissonance is guaranteed to result. Have the players stagger-breathe, if necessary.

For Exercise I, the instructions are as follows:

-

I will assign a unison/octave starting pitch to the class and begin to play a medium-tempo, basic blues progression (no chord extensions) on a play-along CD or comping instrument.

-

On my cue, the students play the pitch and raise the note by half-step on each of my successive cues, which will all be dictating long, sustained note-values.

-

Once upper range is reached, I will cue descending half-steps in the same manner.

-

And the most critical rule is this: “Whenever you hear a dissonance, crescendo—lean into it!” (And when you hear consonance, decrescendo.)

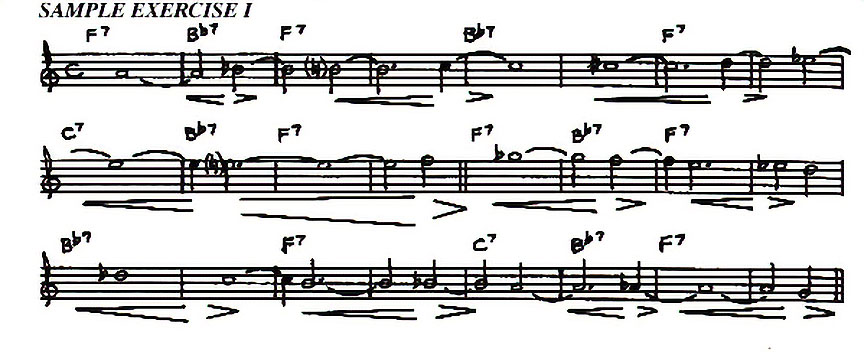

In this exercise I go out of my way to cue dissonant occasions. For instance, given F Blues and a starting pitch of A concert, the following music (yes, music) may result:

If you use a different blues progression, the dissonances and crescendos will vary accordingly. Individual students should try this exercise in and out of class, but remind them to play long note-values and crescendo the dissonances. Eventually the students will be able to recognize and exploit briefer dissonances as well. Note that no chord/scales (other than chromatic) have been discussed; and the accompanying instrument or CD need not alter the dominant-seventh chords to accommodate the dissonance: that’s one of the lessons of the exercise.

Following the exercise I ask if anyone heard any “wrong” notes: virtually no one has answered affirmatively yet! So the point is quickly made that dissonance played convincingly sounds intentional—even if it was accidentally introduced into the solo. There are no wrong notes: “mistakes” can be emphasized and/or repeated, then resolved (often by half-step) to create tension and release. And all a soloist need use is his or her ears—no chord/scales or patterns. (If you wish to demonstrate this further, have a student comp or walk any chords in any harmonic rhythm while you improvise long-value chromatic notes, even shorter chromatics. If you phrase convincingly, you cannot sound wrong despite ignorance of the progression to come.)

The Importance of Themes

For Exercise II, I use a slower blues and the following instructions:

-

Given a unison/octave starting pitch, the class may move only in one given rhythmic and melodic pattern, which uses half-steps above and below the given pitch.

-

Play smooth, legato swing-eighth lines: no rushing, no “Mickey Mouse” phrasing.1

-

I will also cue the pattern’s descent.

-

This exercise once again guarantees dissonance; so again, “when you hear dissonance, crescendo!”

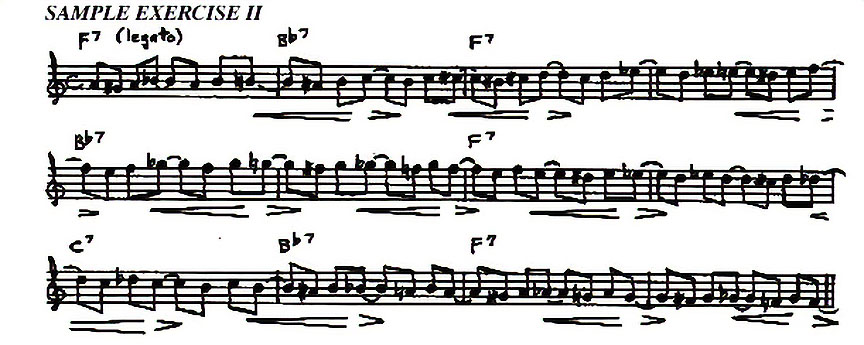

The following music may result over F Blues:

My participants have always agreed that no wrong notes resulted from this exercise. When pressed for a reason, someone will volunteer that the music had a direction, an intent that made it believable. So be sure to point out that this powerful believability stems from the THEME (albeit repetitive): a given rhythm and the chromatic scale. While random dissonance usually sounds mistaken, THEMATIC DISSONANCE IS CONVINCING. It is also interesting, unpredictable, usually enjoyable, and an essential step towards establishing one’s own “sound”—a major goal of aspiring jazz soloists.

Thematic Contour

Many of our most respected improvisers relate their musical lines to contours, shapes that can be repeated, varied, or answered. To demonstrate the power of thematic contour, I link dissonance and disjunct movements in Exercise III:

-

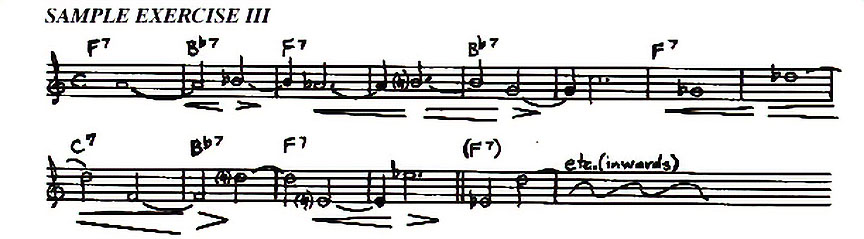

Taking a chromatic line in both directions from a starting pitch, I will slowly cue a double guide-tone line of increasingly extreme proportions over an F Blues.

-

Again, “crescendo when you hear dissonance!”

Because of the recognizably jagged thematic contour, player and listener alike are convinced of the intent of the tension/release (despite ignorance of the chord/scales passing by). If you wish to do so, you can prove that incorporating leaps that are not strictly chromatic would still be convincing because the contour had already been clearly established.

Lyricism and Playing “Outside”

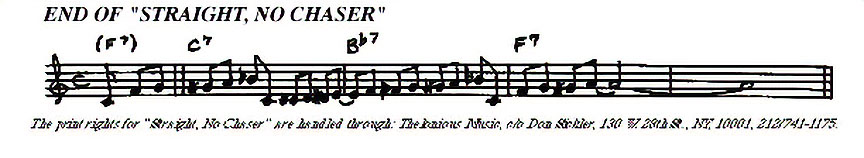

At this point the participants (and you readers) may believe the strength of thematic dissonance but may not be convinced of how directly it can be applied to a creative (i.e., not painfully repetitive) solo. I like to demonstrate its application using one of the best-known blues melodies that highlight chromatics, Thelonious Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser.” Monk’s chord changes were a bit different, but had the tune been written over the basic progression we have been using, the last phrase of it would have been as follows:

As a soloist, why should I be forced to improvise diatonically over such a chromatic foundation? The only element that separates most blues from others is the melody; so I prefer to demonstrate that I (or Monk, or Rollins, or Miles) might well choose to build thematic dissonance over the lyricism of the tune, creating my own lyricism—even if I use only two notes as my building blocks:

Not only does my thematic approach (even with variation or interludes) keep me entirely believable, I am also in the spirit of the tune’s chromaticism rather than just “blowing” over F Blues.

At this point of the presentation most of the participants realize that the “hip” sounds they have been searching for are often simple but thematic dissonances. Playing “outside” seems more accessible to a young player—and it should be! Even the youngest improvisers can learn to handle dissonance thoughtfully, and I use the final exercise to encourage them to do so.

Sequences and Pace

Having proved that a theme is the key that unlocks the door to playing “outside,” one must demonstrate the easiest method to go out and come back: half-step sequences. Why introduce difficult transpositions when a half-step sequence alters a key center by five flats or sharps? (Again, no chord/scales of the blues need yet be introduced, as we are concentrating on thematic development and ears.)

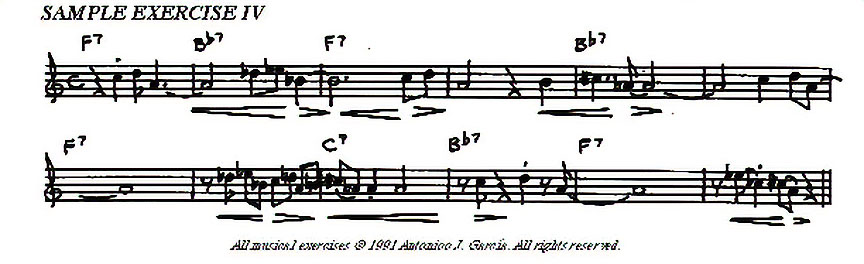

Pick a thematic idea, perhaps of three notes; and play it over the opening of a blues. I suggest drawing its contour on a chalkboard to encourage participants to identify themes visually, in a linear sense. Exercise IV is to be done individually (you first) over the blues as follows:

-

Play the idea.

-

Sequence it a half-step higher.

-

Return it to the original key.

-

Sequence it a half-step lower.

-

Return it to the original key.

-

You must play firmly and slowly, crescendoing dissonances to convince listeners of your intent.

-

You can then repeat any of the three versions of the theme, varying length, articulation, or dynamics; but do not play faster than you can think, as you are only allowed that single theme from which to compose variation. Playing too quickly on “auto-pilot” is the enemy of the improviser!

The following music might result from a thoughtful Exercise IV:

Have individual participants try this, each taking time to develop a sense of pace. (Rests are an essential element of most melodies!) Young improvisers generally play more themes in one chorus than I might in six. By isolating a theme and sticking to it, building variations, players discover a theme goes a long way. Instead of focusing on the typical, fearful question, “what am I going to play?,” players learn to consider instead the much more valuable question, “How am I going to play what I just heard?” Hearing recordings of soloists such as Monk, Rollins, and Miles will prove that theme and pace are not merely tools of the inexperienced: they are the ingredients that shape the music we enjoy.

Often I will have a student improvise some blues choruses without restriction. Then I will isolate one of that player’s themes, play it back, and mandate that he or she use only that theme throughout the next several choruses. (I can also adopt that theme myself, demonstrating a few choruses of variation.) Since the students discover they can improvise creatively—even using two or three-note ideas over chord progressions they might not even know—they are not frustrated as they might be had they resorted to a book of patterns. They are in control: the material in each measure relates to the measures before and after it: no “cut-and-paste” solo patterns, no “auto-pilot”!

It is important to note that as a student’s independent sense of creativity and thematic dissonance takes shape, he or she can discard the “crescendo dissonance” rule at will. By that time, the student’s ears will be well attuned to accepting and handling dissonance.

Alternate Positions

Certain instruments’ construction makes most chromatic sequences incredibly simple. Except for the extreme end of a string or slide, players of stringed instruments and the trombone can use a “fretted” technique to duplicate the hand positions of the original thematic notes, moving the positions to a parallel group either higher or lower. As a trombonist standing with slide parallel to the class, I can clearly demonstrate that an idea played in positions 2-4-3 can easily be sequenced a half-step higher as 1-3-2 or lower as 3-5-4. Players of these instruments are delighted to learn of this advantage, and such sequencing promotes the study of alternate positions/fingerings that are so essential to smooth phrasing.2

The Future

There will be a lifetime to add “left-brain” theoretical elements: chord/scales, “lick” patterns (primarily to promote ear-training and technical facility), and endless analyzation. All will encourage the player to grow beyond the skills presented here—but not to abandon them. By planting the thematic seed first—and by using dissonance to do so—the theoretical elements may be learned in their proper perspective, adding to “right-brain” growth as well. Students will quickly realize that they can improvise creatively now, without fear of “wrong” notes, without much of the frustration experienced by any of their predecessors who might have learned external technical knowledge without stimulating their internal creative drive.

Bassist Dave Holland, whose visit as a guest artist during my graduate studies prompted positive and dramatic changes in my own playing, articulated the following view: “Of course, theoretical understanding is important.... But ear training shouldn’t be left out. Really using your ears, learning the sound of the music first—it’s sometimes the longer route, but is, I think, the more complete route.”3

End Notes

1For further discussion of encouraging smooth swing phrasing, see the author’s article on “Pedagogical Scat,” MENC Music Educators Journal, September 1990, Vol. 77, No. 1.

2For discussion of alternate positions from trombonists, see the author’s article on “Choosing Alternate Positions for Bebop Lines,” ITA Journal, International Trombone Association, Vol. 25, No. 2, Spring 1997.

3Mandel, Howard. “Dave Holland: Creative Collaborator,” Down Beat, October 1989, Vol. 56, No. 10, p. 21.