|

Dale Clevenger.

photo credit:

courtesy

The Instrumentalist |

Revelation I

When I was in college Dale Clevenger, then

principal French Hornist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, came to my school,

Loyola University of the South in New Orleans, as a guest artist/clinician. At

one point he, my classical trombone teacher Richard Erb, and my Concert Band

director Joseph Hebert lined up a half-dozen student brass-players, including

me, to breathe in and out of plastic bread-bags in a closed system. Everyone

else’s bag cycled in size—big/small, big/small—while mine got bigger/bigger/bigger,

until full. Clevenger looked at me and exclaimed in his deep Southern drawl, “Sunnnnnn:

wha-yat the HECKKKKK are yooouuuuuu DOOOinnnn’?”

He had me do the exercise again; and he confirmed: “Clearly

you’re not breathing in a closed system.” In my invented word, I was “snore-breathing”

when playing the tenor trombone. I was taking in air the way I did nearly a

third of every day while sleeping, plus a good deal of the daytime, all while

regularly partially congested: I was breathing in through my mouth and my nose at the same time—which can only be accomplished if you raise the back

of your tongue up a bit or tense your soft palette to engage airflow to your

nose.

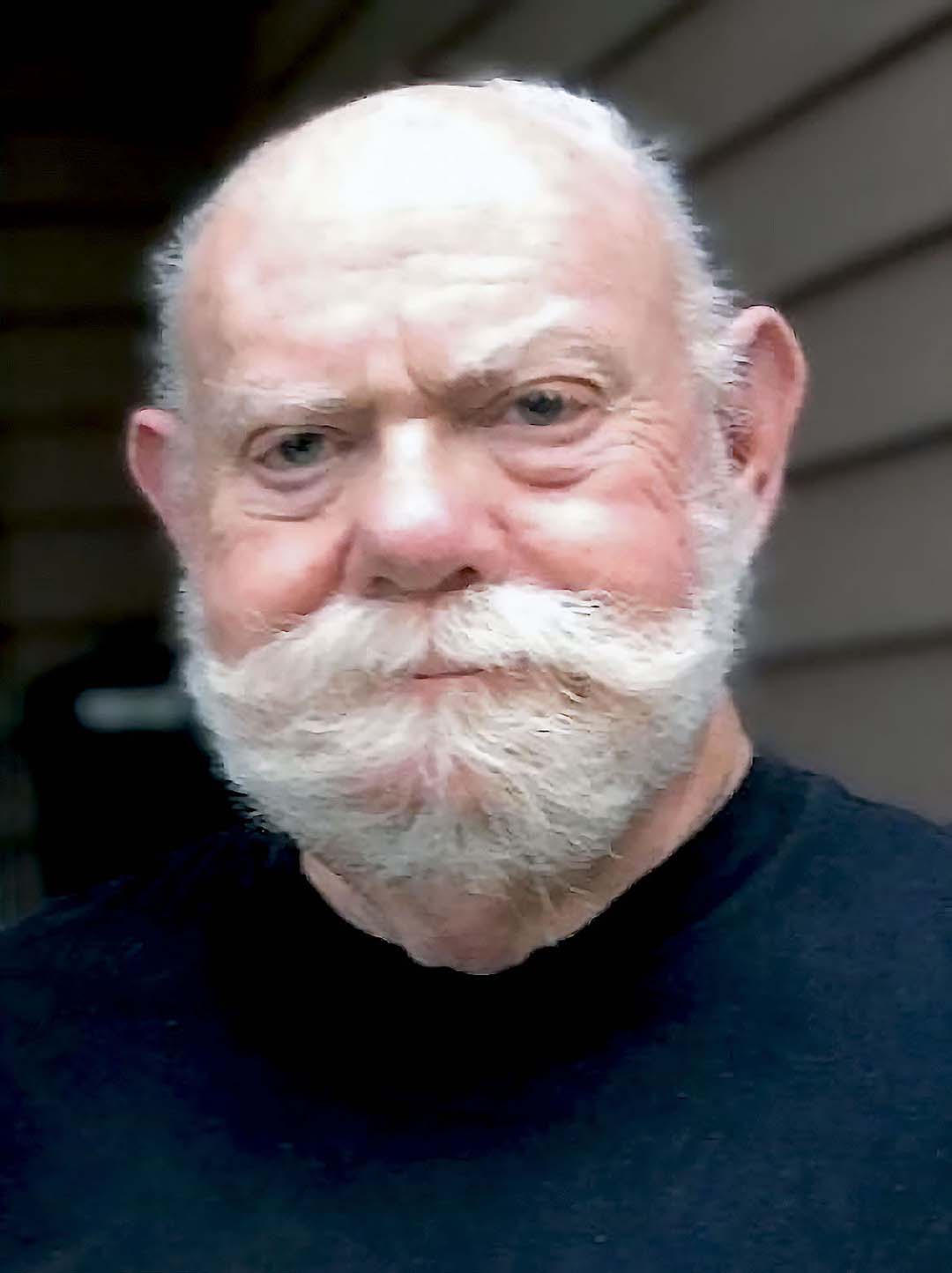

Richard Erb.

photo credit: Michael Grose, courtesy Peter Erb

|

|

That day it took me more than a few minutes of

conscious focus to place my tongue completely down so that I could make the bag

rise and fall like everyone else’s did. It was not easy at first, nor could I

consistently accomplish it. I was shocked, being an almost-20-year-old who

obviously had no idea how to breathe in and out; but that was consistent with

my lifelong history of allergies and asthma: there was no way I would know how others breathe. I was breathing the only “natural” way I knew—which

was unnatural to people who could breathe well.

Clevenger and Erb had both been students of the

legendary CSO tubaist and breathing-guru Arnold Jacobs. Later, in 1980, I went

and took lessons with Jacobs myself, which certainly transformed my musical

life in ways for which Erb had already paved the way.

Erb had told me in one fateful lesson that

year that he didn’t want me to jump out of a window but that I was returning to

each weekly lesson with the same sound-production problems. He felt my studying

even briefly with Jacobs would jumpstart a positive change, and I agreed to

seek lessons with him that Summer. Erb also recommended that prior to my

arrival I mail Jacobs a letter describing my applicable medical history, recent

medical treatment, and possible medically related problems affecting my

music-making. Given Jacobs’ years of formal and informal medical study, he

would immediately understand the context—not that he needed it in order to

improve my playing. The following facts are drawn from that letter.

Medical History

In June of 1980, with a long history of

rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps, I once again underwent examinations from both

an Allergist/Immunologist and an Ear, Nose, and Throat specialist. On the

bright side, my lungs were clear. But a sinus infection was noted, along with a

large number of small, ethmoid polyps. The nasal mucous membranes were

extremely pale, boggy, and approximately 80% blocked. The tympanic membranes (ear

drums) were glistening; and the posterior pharynx (aside the tonsils) was edematous

(swollen with fluid) and injected (congested). Blood tests revealed my IgE (immunoglobulin) level to be 150 (on the higher

end) but my Eosinophil (a white blood cell) count to be 528 (normal

range being 30-350). As has been the case throughout my life, the nurses

tending my series of scratch-tests could not conceal their surprise at viewing my

extreme reactions to all my usual allergens—but it has never been a surprise to

me.

At six months of age I’d

had a severe respiratory tract infection and was on respiratory restrictions

during exercise for three years. I was a highly allergic individual, sensitive

to virtually everything that grew or moved (including being allergic to human

mold!). At the age of 8 I began 18 months of immunotherapy (allergy shots),

resulting in moderate improvement; but over the following decade (overlapping

my starting trombone at age 13) allergic reactions grew; and breathing

worsened. I had moderately severe bronchial asthma until about age 19. A bout

with mononucleosis at age 20 seemed to prompt a relapse into a more severely

allergic state. It was no surprise that cigarette smoke—a staple in the

environment of jazz and nightclubs in which I regularly performed—markedly aggravated

my situation. I often played shows backing such artists as Ella Fitzgerald and

Mel Tormé with a pile of Kleenex concealed in my lap for use during measures of

rest.

|

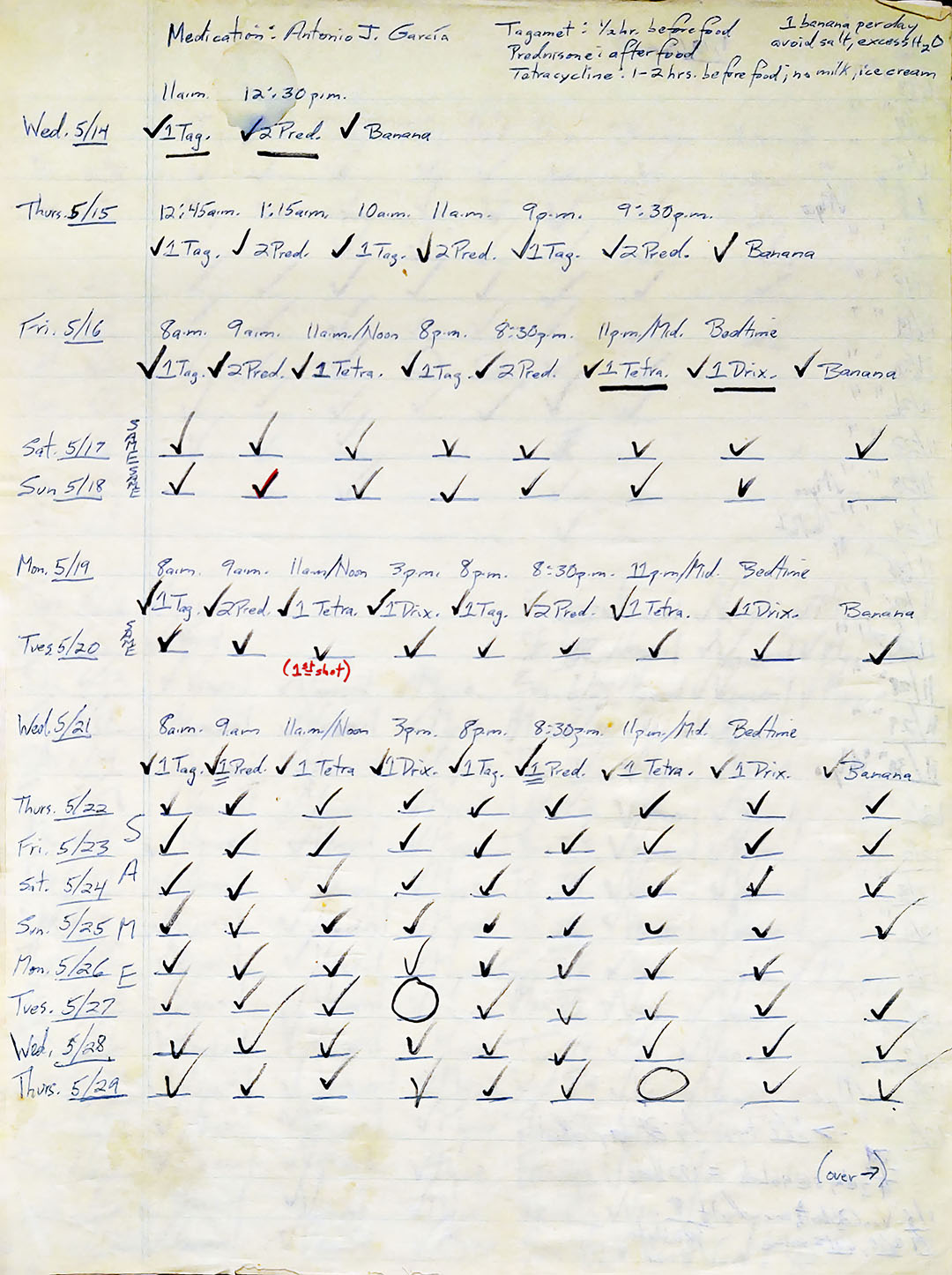

Page 1 of 4 of the author’s May-November 1980 dosage log.

photo credit: courtesy Antonio García |

Medical Interventions

Surrounding the above

examinations I underwent the following treatments to shrink swelling and lower other

allergic reactions:

· Over the span of May

14-June 8, 1980: 60 Prednisone (steroid) tablets, 40 Drixoral (dexbrompheniramine and pseudoephedrine) tablets, 30

Tetracyclin (antibiotic) capsules, and 46 Tagumet tablets (to mitigate the

stomach-issues caused by the other medications).

· Over the course of June

10-July 20, 1980: 2 Afrinol tablets (discontinued because the pseudoephedrine had

aggravated the worsening problem of a racing pulse), 85 blasts of Vanceril (topical

nasal Beclomethasone steroid) in each nostril, and at least 22 oral treatments

with a Mycostatin suspension (to mitigate the potential of fungus stemming from

the antibiotics’ killing of friendly bacteria in my mouth and digestive

system).

· Ongoing use of Vanceril,

Mycostatin, and an outlined program of immunotherapy shots (approximately a

dozen by the Chicago trip).

My doctors reported

that due to the above treatments my nose had improved from 10% efficiency to

70%. However, this increase had not been accompanied by any noticeable

improvement in my trombone-playing. In addition, the pseudoephedrine prompted many occasions when my pulse

was 120 sitting at rest. Initiating trombone-playing would often spike my pulse

into the 160s or higher. If I were home and opted to set the trombone down and

rest for a few minutes, I’d often wake up an hour or more later, exhausted.

These conditions lasted for months past my last consumption of the medicine; so

I learned and employed numerous mindful techniques to regulate my pulse so that

I could not only play trombone but live productively during that time.

Musical Challenges

When playing trombone I’d encountered the

following situations regularly:

· Inconsistency of

sound production (attack and tone).

· Lack of breath

control, air movement (including the Valsalva Maneuver).

· Tendency to contract stomach and raise diaphragm while inhaling.

· Inability to

circular breathe.

· Insensitivity of the

lips, with periodic edema (swelling).

· Lack of flexibility,

inability to trill.

· Inability to

consistently tongue in a marcato style in any range, particularly at louder

volumes.

· Constriction of and

vocalization in the throat, particularly when tonguing.

· Inability to cleanly

attack (even singularly) any note in the range above F1, despite a legato range

often exceeding F2.

· Occasional

uncontrollable “octave-doubling” while playing.

· Preoccupation with

biological feedback (“how it feels”) over musical feedback (“how it sounds”).

· Inability to “teach

myself,” to eliminate problems that recurred after previously having been

solved.

You may have surmised by now that I was

by no means a “natural” player of the instrument. And by the age of 21,

entering my senior year at Loyola University of the South in New Orleans (where

I majored in Jazz Studies), and after eight years of playing trombone, I could

see that any technical improvements had slowed to a stop. The previous year in

particular had seen few advancements in my playing style, those advancements

owed to a gradually better knowledge of general musicianship. I could find

little satisfaction in the classical music medium (in which I wanted to

participate) and encountered continual obstacles to jazz-playing as well. That

said, I was gigging constantly in my native New Orleans, performing 15-30

engagements a month primarily playing written music in jazz, pop, and classical

genres while doing everything I could imagine to circumvent the issues noted

above.

Knowing that Jacobs

expected me to call him once I’d arrived in Chicago to then arrange my

lesson-times with him, I planned a trip there for four nights and three days. I

was eager to get whatever time with him I could. My accommodations at the

Pick-Congress Hotel were just down the block from his studio at the Fine Arts

Building, Room 428, 410 South Michigan. I shipped my tenor trombone from New

Orleans via Federal Express in considerable packing materials rather than leave

it to the airline of the day. I had just turned 21, and this was my first

plane-flight.

I am an aggressive

note-taker and still have my assignments handy from every undergraduate and

graduate trombone lesson I’ve taken. My mindset was no different during my

lessons with Jacobs; and though I did not write constantly during those

lessons, I exited the studio only as far as to sit down on the bench outside

his Room 428, where I wrote for as much as an hour following. While sitting

there I met others of his other occasional students, including a bassoonist

from the Bavarian State Opera (Munich, Germany). It was clear confirmation that

Jacobs’ advice was sought across any instrumental or geographic boundaries.

Visit 1, Lesson 1: Wednesday, August 6, 1980, 2-3p.m.

Jacobs asked me what instruments I played (trombone,

some piano) and what my academic concentration was (jazz). He then invited me

to play anything for him; so I played the melody to “Polka Dots and Moonbeams” (Ex.A) at a suppressed volume, including some notes that wouldn’t speak.

|

Ex. A: Polka Dots and Moonbeams.

© 1939 Bourne Co., My Dad's Songs Inc., Marke Music Publishing Co. Inc., Pocketful of Dreams Music Publisher, and Reaganesque Music Co. |

He then asked

me to perform some classical; so I played Pichareau #1 (Ex.B),

still with some hesitation in the notes.

|

Ex. B: Pichareau 21 Etudes for Trombone, #1.

© 1960 Alphonse Leduc |

He invited me to play some extremely

familiar material; so I delivered Rochut #2 (Ex.C), with much

silence between notes.

|

Ex. C: Rochut Melodious Etudes for Trombone, #2.

©1928 Carl Fischer Inc. |

With my permission, he then

took my trombone and played it with a far better sound than I had. He explained

the conceptual difference between “pressured” air (wind locked inside the body)

and “thick” air (wind moving outside the body), offering that my air was suppressed

inside my body and that the little air that was moving was being interrupted by

the movement of my tongue and by abdominal isometrics.

Jacobs then brought out

a spirometer: an instrument gauge with a tube-attached funnel, measuring not

wind-flow power but wind-flow steadiness. My airstream barely moved the meter;

yet when he blew into it, his air swung the readings fully across the scale. He

said I should visualize the air separating the pages of the music in front of

me, thus thinking of air moving outside the body, not concerning myself

about proper internal (i.e. lung) movement and the like.

The steadiness of my

airstream then immediately improved vastly.

Jacobs offered that I had

a relatively small lung capacity (perhaps approximately 4 liters); so I must

use all my capacity to keep up with players having 6 or more liters. He

said I must try to forget about “feel” (physical feedback). Instead, concentrate

on pre-hearing my desired sound in my head, not worrying about the

actual results as much, and thinking not at all about proper internal function:

function must be a natural act.

To demonstrate, without

warning he threw a pencil at me, which I caught. Jacobs said that proper

breathing would be the result of the same unconscious response to stimuli. So

concentrate on pre-hearing: that artistic input in his estimation was

85% of the requirement. The other 15%, the physical motor movement, requires

only the simplicity of a 5-year-old catching a ball.

My sound was then much

improved.

The author in vocal and instrumental settings.

photo credit: courtesy Antonio García

|

|

Jacobs then brought out

an incentive spirometer: an instrument with two ball-gauges (one for inhaling, one

for exhaling) attached to hoses leading to one mouthpiece. He asked me to buzz

a mid-range note at an intensity necessary to maintain exhalation at a certain

rate. He then removed the mouthpiece and asked me to inhale and exhale (with

steadiness, not power) into the hose so as to move the balls consistently up to

certain level. When I was doing this regularly, he asked me to glance into the

mirror at the result: proper chest-movement created by proper windflow. (Both

Jacobs and Erb encouraged use of the word “wind,” which suggests movement,

rather than “air,” which may suggest a static presence.)

He instructed that I

must visualize the images of the ball-scale and steadiness-meter while playing

so as to improve more quickly. This visualization during performance appeals to

the memory of an additional sense other than hearing: sight, thus

reinforcing my intent to my brain. The brain, subconsciously knowing

much more about my functions (and disabilities) than I do consciously, will direct

my body as it needs to in order to duplicate the sound I’ve pre-heard.

Jacobs invited me to

read Rochut #2 again. He stopped me after a few bars, picked up a book, and

began reading in a monotone, explaining that’s how one reads for information. Then

he began reading as if delivering a speech, explaining that’s how one

communicates to someone else. He said we make the same difference while

performing music: never allowing oneself to read for information, even

during practice. His reason anatomically is that the fifth and seventh

cranial nerves are attached to the embouchure. The fifth receives physical

feedback (i.e., a sensor nerve for “learning”); the seventh is a motor nerve

that, given proper stimuli, operates the lips for “presentation.” We must be

sure that attention is given to presentation at all times.

I must state here that

prior to this lesson I had often wondered as to how it was possible that I

could have occasions when my embouchure had felt terrible while I played

markedly well, as well as occasions when my embouchure had felt great while I

played poorly. Every brass-player I’ve ever discussed this with has experienced

the same. And the reason, simply put, is that the nerve that tells the brain

how our “chops” feel is completely different from the nerve from the brain that

operates those “chops.” So if our mental focus is correctly aimed at

pre-hearing our sound, it is possible to override poor physical

sensations with a directed mental image. And conversely, if our mental focus is

poor, a great embouchure and windflow may not result in a fine performance.

I then played Rochut #2

with improvement.

He suggested that I work

on smaller phrases with proper sound now, saving more lengthy phrases for

later. He emphasized that I must not be subjective while playing: I cannot

analyze and play simultaneously. I must be objective: perform!

He then asked me to play

some jazz, requesting the “When The Saints Go Marching In” melody. My rendition

ignored the word “the” and loudly hit “Saints.” When requested to sing it, I

surprisingly sung it the same way. So he asked me to play the melody again,

emphasizing the note for “the.” I was unsuccessful. But when he then asked me

to pre-hear what that new version should sound like, I delivered the

phrase successfully.

He asked me to play the

Arban scales on (my edition) p.63, #1 (Ex.D).

|

Ex. D: Arban’s Famous Method for Slide and Valve Trombone, p.63, #1.

©1936 Carl Fischer Inc. |

My playing

emphasized some notes over others. But when he then asked me to pre-hear a

smooth version, it worked: I delivered evenly phrased scales.

He then stated

something I’d heard from Richard Erb many times before. When exploring new

phrasing, the physical feedback I received would different than before. But “different”

didn’t mean “wrong” any more than “familiar” meant “right.” (As I have often since

stated to my own students, my two criteria for assessing a new result are: “does

this version suit the genre better?” and “is anyone hurt?” If it sounds better

and there’s no apparent injury to one’s embouchure or nearby musicians’ ears,

you’re probably onto a good thing!)

Jacobs said that I must

expect, though, that some skills would be weaker when playing in this “new” style until I’d worked on them sufficiently. He suggested

that I buzz jazz melodies on the mouthpiece—nothing slow enough to self-analyze,

just performing on the mouthpiece—for at least a half hour per day.

(Doing so on my bass trombone mouthpiece in later years also had a profoundly

positive effect unlocking a melodious style on that instrument.)

He closed the lesson

saying that we must meet again to work on the movement of my breathing (so as to

lose abdominal tenseness) and use of my lung capacity.

Visit 1, Lesson 2: Friday, August 8, 1980, 11a.m.-Noon

|

|

"Four Cannons and a Relic": The Phil Collins Big Band trombone section pre-concert at the Zürich Landesmuseum, 1998. Mark Bettcher, Arturo Velasco, Antonio García (bass trombone), and Scott Bliege.

photo credit:

courtesy Antonio García |

The Phil Collins Big Band trombone section: Scott Bliege, Arturo Velasco,

Mark Bettcher, and Antonio García (bass trombone), 1998.

photo credit:

courtesy Antonio García |

After I briefly warmed up, Jacobs emphasized that

I must give each note equal importance, must picture the sound in my head. He again

brought out the incentive spirometer (with two ball-gauges, one for inhaling,

one for exhaling) and asked me to make the two levels match while breathing. He

stated again that my pulmonary function was fine but that I must use it fully. After

I played some scales, he again emphasized equal importance to all notes.

Jacobs explained that I

should visualize breathing in and out of my mouth, not out of my lungs

or body, because otherwise my muscles would move in a fake manner mimicking air

intake while actually not filling my lungs to capacity. He asked me to move my

stomach to enlarged and shrunken positions without breathing so as to

notice this “black and white movement” of the expanded and emaciated stomach walls.

He then suggested that I think of breathing not

as horizontal expansion and contraction but instead as vertical, like a piston.

About half the air supply involves lowering the diaphragm; if that instead raises

during intake, considerable air is lost. And yet, he said, I could not specifically

order my diaphragm to move, any more than I could order my spleen to do so: my

diaphragm would move when air moved properly in and out of my mouth, thus

expanding and contracting the lungs above the diaphragm.

My decibel level was generally

too quiet; my expectation of what was coming out of the bell didn’t match the

decibel meter’s assessment. He told me that I should practice with a strong,

soloistic forte so that there’s room to crescendo and decrescendo, and with

equal importance to each note.

Jacobs stated that our

lungs have the capacity to hold so many ounces of air, but our abdominal muscles

have capacity to exert 10 or 12 pounds of isometric force when used in

opposition to each other. So we must weaken all our muscles in the abdominal

area when playing so that there’s room to be flexible with our air and sound.

He stated that “strength is your enemy; flabbiness is your friend.”

He suggested I over-breathe

(breathe “too often”). Have air to waste: don’t get caught playing while in the

downward end of the respiratory curve. If need be, shorten phrases in favor of maintaining

a soloistic sound; length will come later.

Jacobs informed me that

the reason why my stomach wall wouldn’t expand during inhalation was because I

had never contracted it during exhalation! So he emphasized that I must, for a

while, give conscious attention to my abdominal movement in order to create new

stimuli. Eventually new, natural stimuli would take over the function without

my conscious attention.

He asked me to play long

tones: Arban p.17, #1 (Ex.E).

|

Ex. E: Arban’s Famous Method for Slide and Valve Trombone, p.17, #1.

©1936 Carl Fischer Inc. |

Practice giving full attention to picturing

the sound and (for a while) to proper abdominal movement. Play jazz ballads at

strong volumes.

His summary to me was

that simplicity, in general, is the key for solving most physical problems.

Given the proper musical picture, the brain will command the proper motor-work

(i.e., catching the pencil). Brass-players, unlike woodwind-players, have “flesh

and blood reeds.” By playing at consistently louder volumes, the lips will

learn to respond; otherwise, they can lock off air just as abdominal tension

and tongue-placement had for me before this day.

Most importantly, give

attention to the “art” over the motor-mechanics.

Interlude

The improvements to my playing were immediate,

profound, and in majority lasting. Also important was the feeling of relief that overcame me after even the first lesson: relief that endless performance-problems

seemingly out of my control were now becoming matters I could control. I

had a future. By no means had I become a virtuoso player, but I had received

stimuli and direction from Jacobs that supercharged the perspectives already

given me by Erb and more. In the months following, I was actually improving in

lessons and on my own and enjoyed a senior year less fraught with negativity

surrounding the trombone. I was focusing on pre-hearing my sound and far less

so on the mechanics of trombone-playing.

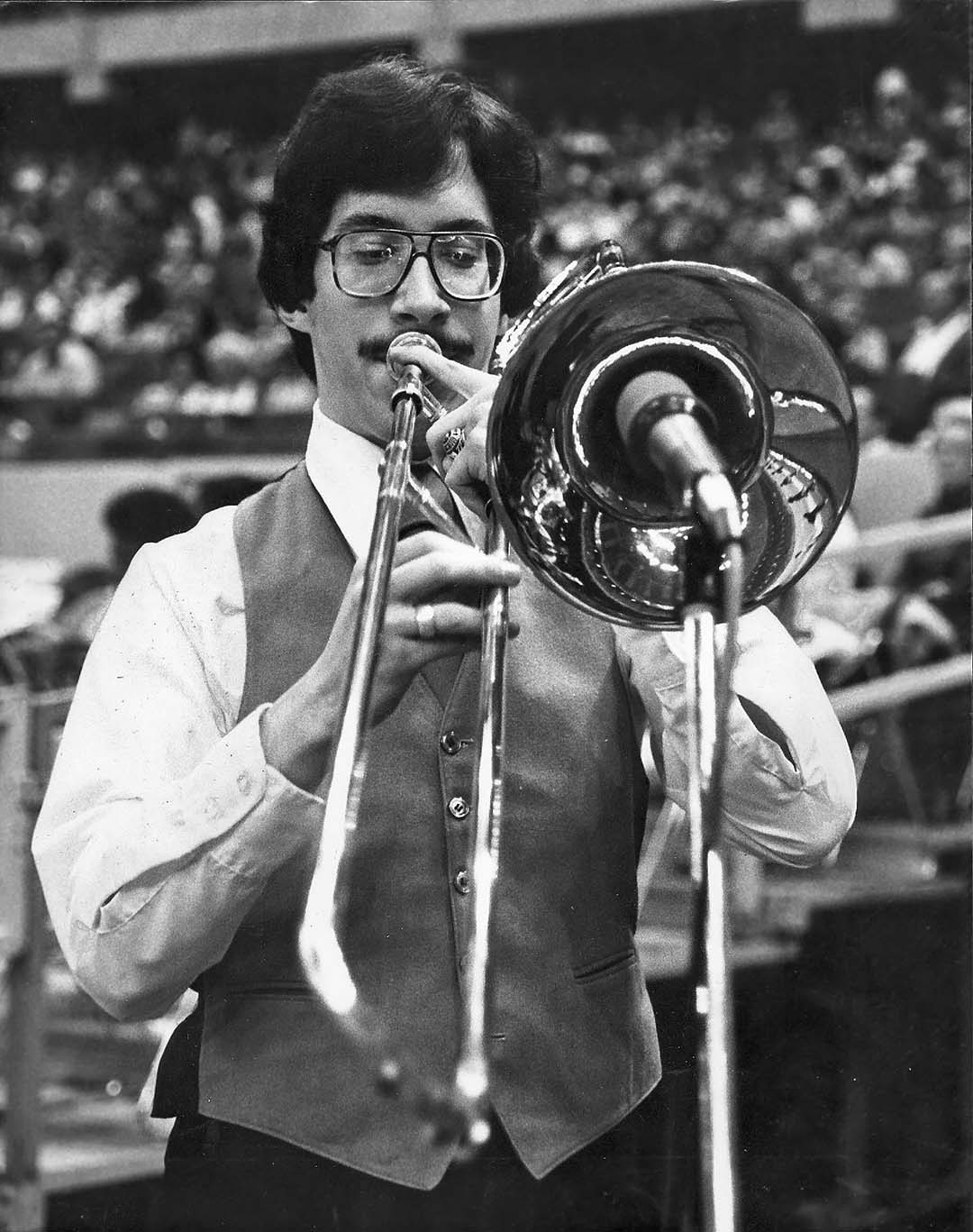

|

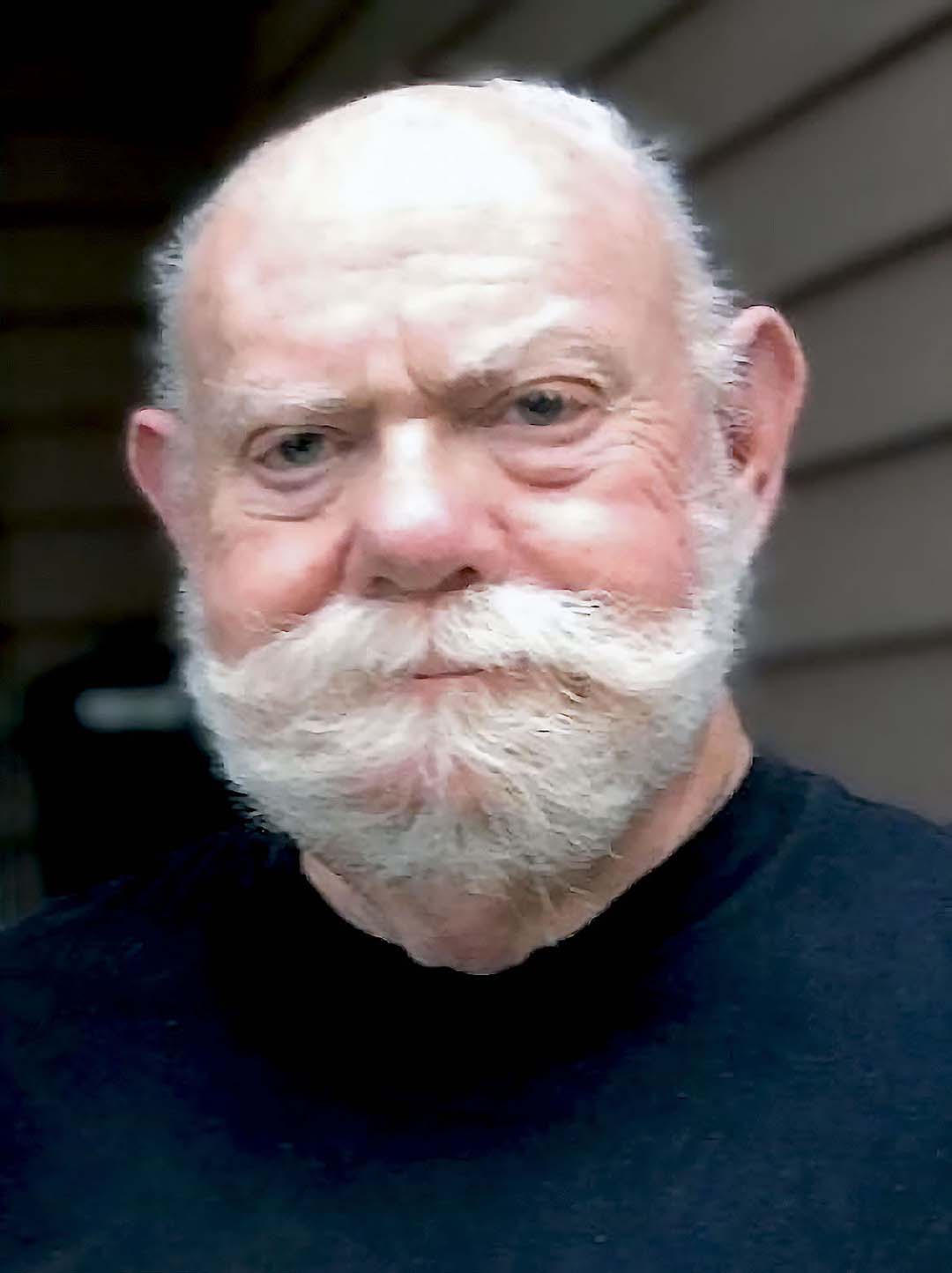

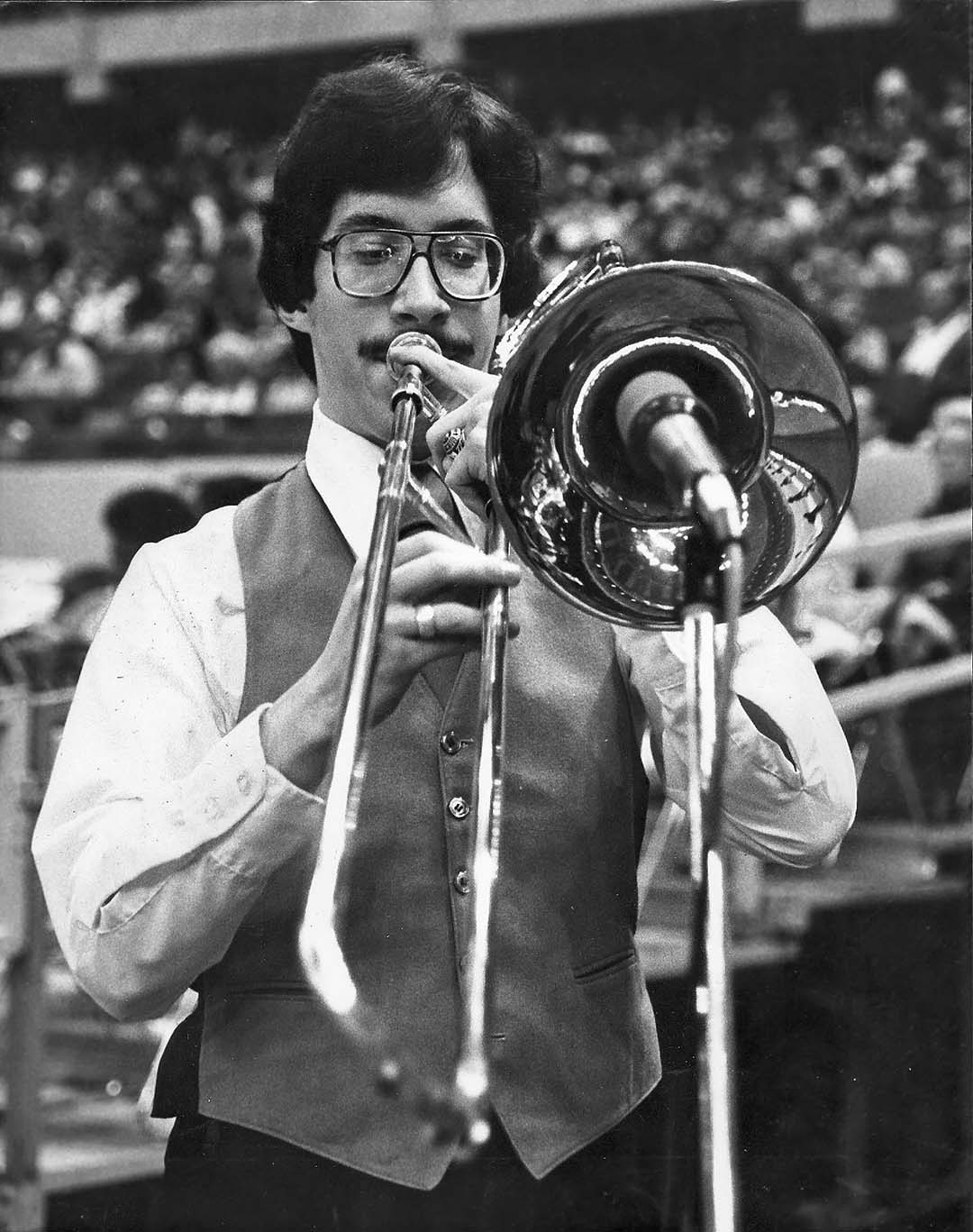

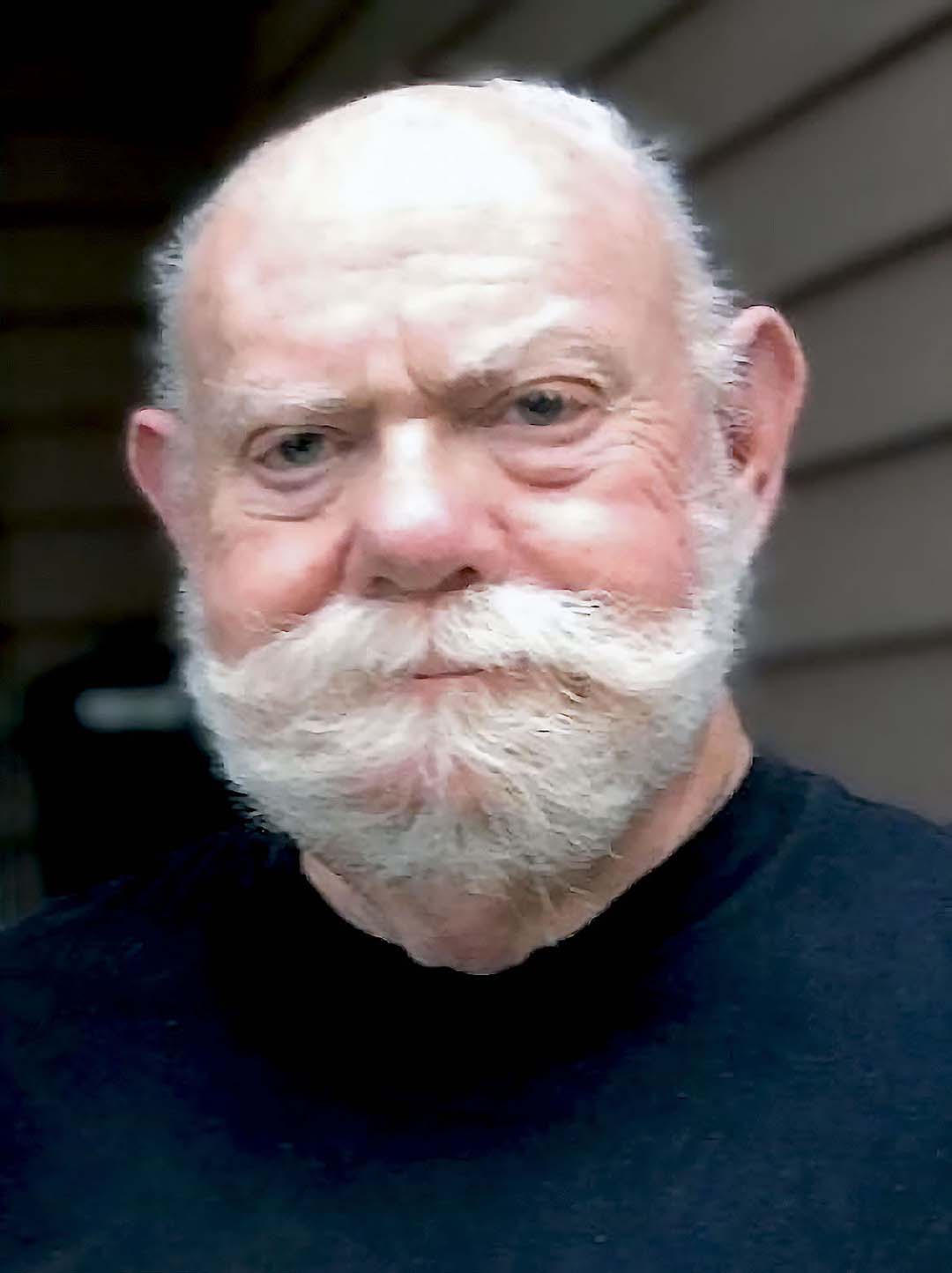

García as tenor trombonist of the New Orleans Saints Combo, circa 1980, a recurring job he received from Dr. Joseph Hebert, providing experience in front of 70,000 attendees each game.

photo credit:

José L. García II |

Prior to my lessons

with Jacobs, I had actually been doing isometric abdominal exercises as a

workout. But given his assessment that I had been exerting those muscles unnecessarily

while playing, to my airstream’s detriment, I gave up those exercises

immediately. Perhaps I could have learned to relax my abdomen during

performance while continuing my workout-regimen, but I decided I needed every

bit of momentum on my airstream’s side while proceeding to learn how to focus

on pre-hearing my best sound of the music before me. I was also aware that

others’ pedagogical approaches actually favored using isometric tension as a

breathing tool, but I was not interested in exploring an aspect of abdominal

tension so closely related to my previous difficulties.

I’d listed the Valsalva

Maneuver as one of my musical challenges. You can find plenty of information

online regarding this tense way of breathing, including statements from Richard

Erb within his article/book-chapter listed below. As a form of bearing down

while breathing, it requires a closed glottis so is utterly contradictory to

good windflow. My first lesson with Jacobs freed me from my subconscious use of

the Valsalva Maneuver, yet he had never mentioned the topic. It was simply

impossible for me to employ that tense tactic while pre-hearing the desired

music and visualizing my airstream moving vertically through my torso and out

my mouth at the pages of music I sought to move. Such a change emphasized to me

the pedagogical concept shown me by both Erb and Jacobs: saying “no” to a bad

habit is rarely effective; but it is often easy to introduce a new, more

desirable habit to overwrite the old one. Erb would at times overwrite my

body’s tension by placing me in his office chair and requesting that I play

Rochut #2 or similar while he gently wheeled me back and forth and around the

space. I had to let go of the rigidity of my body in order not to fall out of

the chair, resulting in better tone and attacks that I could then recapture

while standing.

I should mention that

Jacobs’ pedagogical manner was unimposing. He immediately conveyed a welcoming

attitude, as if I were an invited guest to his home. He offered his

instructions as the suggestions of a mentor I’d requested join me, not

posturing himself as an acclaimed god whose every word should be inscribed on a

granite wall. I thought of him in a grandfatherly way—a grandfather with

tremendous knowledge—and if Richard Erb were a mentoring trombone-father to me,

then that analogy regarding Jacobs was appropriate.

I definitely felt our relationship was

founded on two-way respect: I of course entered the room seeking his pending

perspectives during my lesson; but my feeling was that he also respected that

I’d invited his insights. Not every student senses that coming from a teacher

during lesson one, but I was fortunate to receive that from each of my formal

trombone and jazz mentors.

After graduating with

my B.M. in Jazz Studies in May 1981, I decided in the Fall of that year to

audition for graduate school the following Spring for potential entry Fall

1982. My chosen destination was The Eastman School of Music, whose jazz and

classical recordings I had heard and where many of my professors had attended.

John Mahoney (left) with Garcia at a Ray Wright Tribute concert, Eastman School of Music, October 2012.

photo credit: courtesy Dorien Mahoney

|

|

My jazz trombone and arranging teacher, Prof. John Mahoney

(an Eastman alumnus), advised me that he could not yet recommend me for

graduate jazz performance but suggested I showed promise towards entry into a

graduate jazz writing degree. Towards that end, I began assembling my writing

portfolio and practicing my trombone towards that goal while continuing to gig

heavily in New Orleans. His advice would soon change my life for the better.

Meantime, one airline was

offering an option for multi-city routing at a very low price; so I scheduled

an itinerary for February 1982 that began with in Rochester, NY for my Eastman

audition, then took me to Giardinelli’s in New York (where I purchased my bass

trombone) and Chicago (to study again with Jacobs) before returning to New

Orleans. I was fortunate to receive one more lesson from Arnold Jacobs.

I was not fortunate in that the trunk

in which I’d transported my horn was lost on the shuttle van ride from the

Chicago airport to my hotel. After calling all the preceding hotels on the

shuttle route, I had to file a police report and then contact Jacobs for a referral

to a local music store. It was so kind to rent me a wonderful trombone for a

few days at such a low cost that could only have been due to the value of a

referral from Arnold Jacobs. I also had to venture out in the snowy city to buy

a couple of sets of winter clothes for my stay, as mine were in the trunk!

(Part 2 of this article, to be published July 2025, will explore the author’s third lesson with Jacobs and lessons learned since, plus additional medical interventions, confirmations of Jacobs’ pedagogy, subsequent revelations, and potential exercises, with nine more videos.)

* * *

Richard Erb.

photo credit: Michael Grose, courtesy Peter Erb

|

|

This article is dedicated to Richard Erb,

with whom I studied from September 1977-June 1983. He passed away April 25,

2023, leaving behind a legacy of so many accomplished low-brass musicians whom

he had mentored over his career at Loyola University New Orleans and for the

National Youth Orchestra of Canada, as well as decades of marvelous

performances as bass trombonist of the New Orleans Symphony and Louisiana

Philharmonic Orchestra. Read his article “The Arnold Jacobs Legacy,” published

in The Instrumentalist of April 1987 and republished that same year as a

chapter within the book Arnold Jacobs: Legacy of a Master by The

Instrumentalist Company. Text of that chapter can be found

online. View a lengthy video-interview with Erb

regarding Jacobs’ mentorship on TubaPeopleTV with Michael Grose. And in the December 1983 The

Instrumentalist you can read “The Dynamics of Breathing with Arnold Jacobs

and David Cugell, M.D.” by Kevin Kelly.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of

Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz

Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music

Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for

which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond

High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola

University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic,

chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including

grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk

Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and

has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh,

Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors

include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop

songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor

Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music

Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob

Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for

independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. One of his recent commissions was performed at Carnegie Hall by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra.

A Conn-Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the

jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist,

bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including

Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave

Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North

Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced

recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave

Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is

the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night

in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins:

Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer,

he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated

sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts &

Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local

artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Most of all, Tony is dedicated to assisting musicians towards finding their joy. His 35-year full-time teaching career and countless residencies in schools have touched tens of thousands of students in Canada, Europe, South Africa, Australia, The Middle East, and across the U.S. His collaborations highlighting jazz and social justice have raised hundreds of thousands of dollars, providing education to students and financial support to African American, Latinx, LGBTQ+, and Veterans communities, children’s medical aid, and women in jazz. He serves as a Research Faculty Member at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. His partnerships with South Africa focusing on racism and healing resulted in his performing at the Nelson Mandela National Memorial Service in D.C. in 2013. He also fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program.

Mr. García is the Past Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal.

He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and

Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz

Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His

book Cutting the Changes: Jazz

Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the

opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He

is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching

Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by

Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he

served as Editor of the Jazz Education

Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and

for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997

Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education

coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to

develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular

grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of

IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of

Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is

perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the

multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path

through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson,

“The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s

very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s

wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts

without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to

present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of

trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a

series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that

will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes:

“Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an

oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s

“splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd

arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously

uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing”

and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most

prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and

“first-class writing of special interest.” The

Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely”

composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications

whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he

wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from

Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such

artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John

Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

Tony is the Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute. The partnership he created between

VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of

KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He

has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank

Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the

Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on

Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the

Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly

published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz

Improv; Music, Inc.; The

International Musician; The

Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American

Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois

Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards.

Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at

Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz

Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years

directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at

Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as

the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and

nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of

434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Arts’ 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service, in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame, and is a 2023 recipient of The Midwest Clinic's Medal of Honor. Visit his web site

at <www.garciamusic.com>.