|

This article is copyright 1989 by Antonio J. García and originally was published in the Music Educators National Conference MENC Journal, Vol. 77, No. 1, September 1990. It is used by permission of the author and, as needed, the publication. Some text variations may occur between the print version and that below. All international rights remain reserved; it is not for further reproduction without written consent. |

Pedagogical Scat

by Antonio J. García

Students in swing bands and choirs sometimes have difficulty producing the most fundamental and appealing stylistic elements of jazz—those of rhythm and phrasing. Antonio García shows how directors can use listening and scat-singing to help their ensembles and soloists really swing.

“I’ve got a fine group of young students in my jazz band, but they still seem a bit stiff. Could you help them to swing better?” “My chorus can’t seem to loosen up its phrasing enough to sound natural on a swing tune. What should I do?” “My ensemble’s together but my soloists need assistance. How should I introduce them to improvisation?”

As I visit school jazz band and chorus rehearsals, these are the questions most frequently raised by the groups’ directors. Since most of these directors face the challenge of meeting their goals with what seems like too little rehearsal time, it is not surprising that many are reluctant to spend that time doing anything other than reading and rehearsing arrangements in the expected fashion. However, the key to students’ accelerated learning lies in making use of their ears and voices. Students in orchestra or band can best play what they can hear and sing, and the same is certainly true for young musicians playing instruments in jazz band. By using “pedagogical scat” you can develop more than your students’ vocal and instrumental skills—you can develop their musicianship. In the process, the swing feel of your ensemble and soloists can improve far more quickly.

I use exactly the same techniques for band and for chorus because precisely the same musical principles apply. The students in most instrumental groups have less experience with scatting than do those in vocal ensembles, however; so I will address the illustrations that follow primarily to the jazz band director.

Laying a Foundation

First and foremost, your students must listen to jazz in order to begin to assimilate it or decide if they even like it. It is impossible to paint a picture of a tree without having first sensed one through sight (perhaps even through sound and touch); similarly, it is unlikely that any student will develop a satisfactory jazz style without having heard some quantity of quality jazz. Although this process of assimilation, which has a long tradition in jazz, is often ignored in the time-restrictions of the classroom, students can learn to enjoy jazz outside the classroom (with occasional in-class discussion).

I suggest you attempt to obtain, through your school library or your own resources, at least a dozen jazz albums of large and small ensembles (primarily in the swing and bebop styles). Add a modern “fusion” album to attract contemporary ears, but remember that your goal is to acquaint students with the swing phrasing they rarely hear on “top forty” radio stations. Few ensembles face insurmountable rhythmic troubles on rock, bossa, or Latin charts due to the “straight eighths” common with classical music.

Then, through band or music appreciation class, require students to listen to an album from their collections or yours and write a one-page report on what they do and don’t like about it, preferably describing the means by which the artists seem to accomplish the sounds the students like. Spread additional reports on other albums across the school calendar. By encouraging your students to become aggressive listeners, they will improve their ensemble- and solo-performance styles.

Every student wants to hear recordings by the major performers on his or her instrument, but make sure that students listen to albums of instruments other than their own as well. Any listening list would be too short; but I would start with the Count Basie and Woody Herman Orchestras, followed by Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue album, virtually any Sonny Rollins sax recordings (though the ones from the ’50’s and ’60’s might be most helpful at first), the breathtakingly lyrical pianist Bill Evans, the beautiful sound of trombonist Urbie Green, vocal stylings of the Manhattan Transfer, and the absolutely essential Ella Fitzgerald (who recorded several albums with Basie as well). These artists can provide a good introduction for your students.

From Ears to Voices

Choose for yourself certain ensemble passages and improvised solos on the albums that you judge to be singable and lyrical. Next, require students to listen on their own to a selected passage enough times to be able to sing along with the recording in class later on. This passage may be chosen by the students or by you, but remember that it is extremely helpful if a solo is one to which the students are attracted. Singing these excerpts serves several essential functions: it promotes ear-training (aiding pitch), style-training (helping phrasing), and the lowering of inhibitions (bringing about a blossoming of students’ instrumental dynamics as they sing out).

Students’ choices of scat syllables and voice range do not matter so long as they match the pitch and phrasing as closely as possible. (Listening to Ella will help!) If a student “steps in” a rest, he or she is revealing the need to have listened to the recording more. Do not allow any student to notate the passage: the goal here is internalization of the music.

A perfect example of this approach can be examined utilizing Miles Davis’ trumpet solo on “So What” from the Kind of Blue album. This solo (over Dm and Ebm chords) is so lyrical and technically easy that the members of any junior high ensemble could learn to sing along with it individually or as a group. Encourage your students, particularly soloists, to transfer the solo to their instruments a bit at a time after they can successfully scat the passage. You should do the same, especially if you are also a beginner in jazz performance: the students will respond to your enthusiastic example.

All of my college students prepare passages by singing along with the recorded solos and then improvising scat-singing over the same chord changes as the recording (replaced by piano or guitar) before being allowed to attempt the same on an instrument. Using the voice, students find no barriers between the brain and the sound, no limitations of instrumental technique. By temporarily laying aside the instrument, the student is forced to concentrate totally on the melodic content of the improvisatory lines rather than facing the distraction of valves, keys, and tired “chops.” Often students will explore melodic terrain vocally that they would never have traveled on their instruments; then they return to their instruments with an initial concept of what it is they are trying to play. Students who are as reluctant to solo as they might be to read their own poetry aloud will become less self-conscious about their creativity.

Finally, remember that jazz is heavily rooted in a vocal tradition. Virtually all vocalists (jazz or classical) strive for the technical accuracy and facility offered by the valves and keys of mechanical instruments; and virtually all instrumentalists crave the lyricism and fluidity of a vocal style.

Ensemble Swing Phrasing

I often ask directors if their group’s problems are rooted primarily in playing correct pitches or in phrasing rhythms correctly. Almost without exception, proper phrasing of swing rhythms is the more troublesome stumbling-block; and the solution is almost exclusively a vocal approach.

Music is perhaps the most abstract of all the arts. Jazz, due to the fact that swing rhythms cannot be accurately notated on paper, is perhaps the most abstract of all notated music. In order to play it (or teach it), the rhythmic feel must be internalized, independently felt without the use of mechanical instruments. The proof of internalization is enthusiastic and accurate scat-singing. Through “pedagogical scat,” students’ “chops” are saved from repeatedly drilling passages that do not need melodic pitch attention. Using it, I can rehearse an all-district band for a long weekend and still have the players fresh for the concert.

Using monotoned scat syllables, concentrate on passages’ rhythmic characteristics and general melodic contours. You must be able to examine a troublesome passage, reduce it to its best rhythmic phrasing, demonstrate it to the students via scatting, and have the students scat it back. With this guidance, your students can learn to examine and reduce passages to proper scat phrasing on their own, providing a major contribution to their musical growth.

Basic Scat Syllables

Scatting is best accomplished “free-style,” using syllables chosen by a moment’s inspiration. However, teachers and students unfamiliar with what syllables might best match an intended “feel” can benefit greatly from using an assigned set of syllables. These syllables are applied in a manner not unlike traditional sight-singing in classical theory—though only in rhythmic terms.

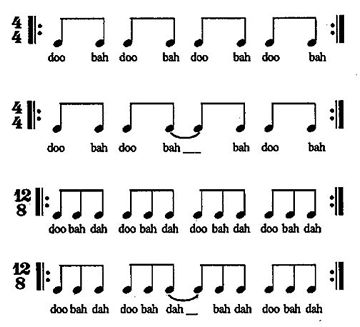

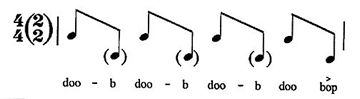

Begin by assigning the syllable “doo” to all full-value downbeats, “bah” to full-value upbeats (in duple divisions of the beat) or middle-eighths (in triplet-beat division), and “dah” to all full-value final eighths in a triple division. Using a sheet of paper to cover up the syllables printed below, slowly work your way through the following examples of swing eighths and evenly divided triplets. Once you can maintain a tempo, be sure to snap your fingers on beats two and four to simulate the drummer’s sock cymbal in a swing feel:

|

Notice how the syllable “doo” encourages full-value downbeats, avoiding the clipped “Mickey Mouse Song” interpretation so common in younger students. Also note how these syllables allow for a relatively easy articulation even at the fastest of tempos. (The appropriateness of the syllables can be proven by attempting to reverse their order.)

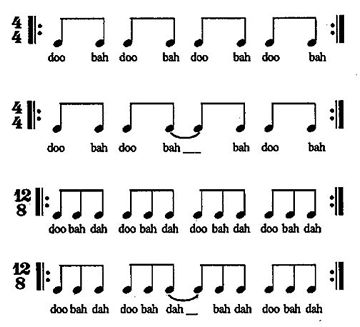

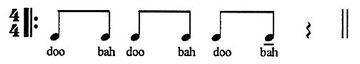

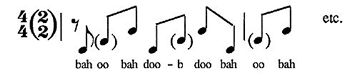

For short-value notes, assign “dit” to downbeats, “bop” to upbeats (duple division) or middle-eighths (triple division), and “dop” to final eighths in a triple division. The three initial consonants correspond to the full-value syllables, as do two of the vowel sounds. Also, these three short-value syllables imply an accentuated attack and well-defined, percussive release; yet the internal vowels encourage enough length for the short notes to “speak” as would a voice. (Rarely are notes in jazz so short as to be “pecky.”) Explore the following examples, eventually snapping your fingers on two and four:

|

Given these six syllables, you can drill yourself and your students by swinging any worksheet of classical rhythms built on eighth notes or longer values. Use a published drill or draw up your own for use by your band, asking the members to scat in unison or pitting one half of the band against the other scatting a different portion of the sheet. Do not allow your students to pencil in the syllables! As problematic as rhythmic reading and swing phrasing are, too few directors encourage their students to work on their rhythmic skills in this concentrated manner. having the students work with the horns in the cases is by far the quickest way to solve these problems. Be sure to involve your rhythm-section members in these scatting exercises as well: proper phrasing of swing lines will aid their accompanying skills as well as their soloing skills. To see and hear sound files of several rhythmic-phrasing examples pertinent to the this article, visit the related page on the VCU Jazz web site and then click on "Required Rhythmic Reading.")

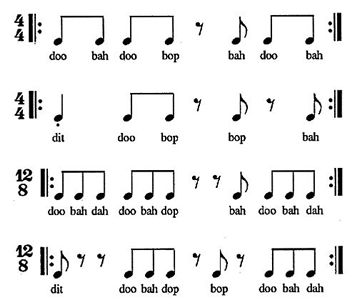

The final group of syllables to be employed involves the concept of “ghosted” notes, notes whose articulations are “swallowed” in order to promote the importance of their neighbors in phrasing a swing line. Ghosted notes are sometimes shown with parentheses or by using x-shaped note-heads. But they are often not clearly marked on a published page of music; they may be notated like any other notes.

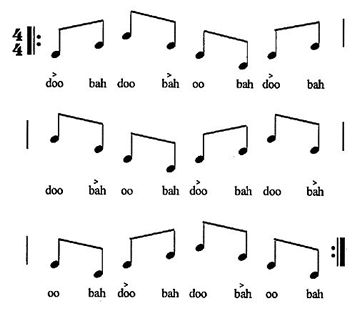

Only full-value notes are truly applicable for ghosting. By removing part of the syllables’ construction, assign “oo” to ghosted downbeats, “b” (not pronounced with a vowel, just closing the previous vowel) to ghosted upbeats (in duple division) or middle-eighths (in triple division), and “ah” to ghosted final eighths in a triple division. Examine the following:

|

You can use pedagogical scat to help students learn about the concepts of ghosted notes and how to identify them, but start with the observation that the final note of any phrase is rarely if every ghosted: all phrase endings should end articulately, regardless of the dynamic level involved.

Application: Kicks

Now that you have learned these nine syllables, you’ll need only three of them to scat successfully Figure 1.1 Don’t look at the printed syllables until you’ve tried working them out yourself, and snap your fingers on two and four once you can maintain a tempo:

|

If you doubt the usefulness of these syllable placements, try scatting Figure 1 using only “doo” (as many novices will)—it won’t swing nearly as well. So if your ensemble is tripping over such phrasing, have your students use this system to scat it!

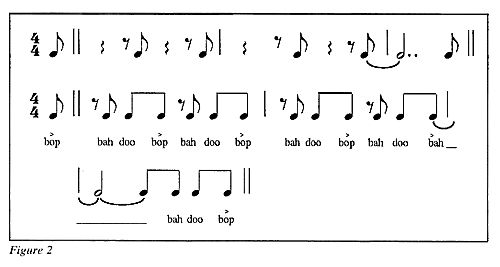

This passage also illustrates one of the most common difficulties in swing: proper timing of off-beat “kicks.” The secret of success is to supply scat-syllables internally for the rests as well as for the kicks, thus simulating drum fills. So, if the horns are to play the upper line in Figure 2, they should scat the lower line as a guide for proper placement:2

|

Notice how the syllable “bop” promotes sufficient length for the kicks to “speak.”

Application: Cross-Rhythm

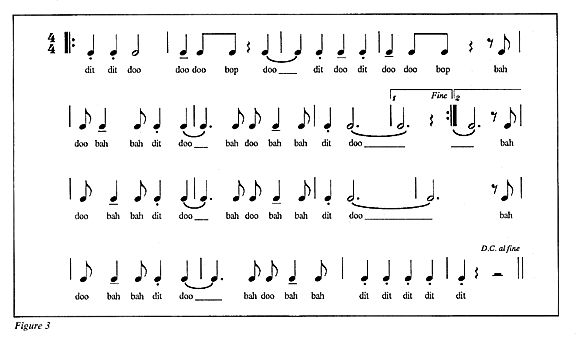

You’ll need only four syllables to complete Figure 3:3

|

Measures 5-7 of this example illustrate another common characteristic (and potential difficulty) of jazz phrasing: the cross-rhythm. Examine this group of six notes over three beats:

|

This passage can be made a cross-rhythm by placing the three active beats repeatedly across a 4/4 bar line, perhaps having the general melodic contour shown in the following example:

The effect of the cross-rhythm is then aided by an important rule: accent changes of direction. This means that the notes on beats 1, 2+, 4, 1+, 3, 4+, 2, and 3+ are accented as in the above example. The corollary of that rule is as follows: if a normally weak beat (such as 2+ in the first measure above) is accented by change of direction, the note immediately following such an accented weak beat is probably ghosted so as to become less accented and (thus less important).

By using this rule and its corollary, you’ll find that three syllables will give you a true feel of six notes (and not merely three beats) against the common time signature. Don’t forget to snap your fingers on beats two and four once you gain tempo:

|

Cross-Rhythm and Ground Beats

If you’ve tried scatting the previous example with proper syllables, accents, and finger-snapping, you probably experienced the “tug-of-war” of the passage against the snapping. Well-chosen scat syllables highlight cross-rhythms in a way that a line of “doo” syllables cannot.

When working with an eighth-note cross-rhythm, do so over the ground beat: the largest common denominator possible. At a moderate tempo, the sock cymbal’s half-note pulse is rooted on beats two and four. As tempos quicken, the pulse moves to half-notes on one and three (as in a brisk cut time), regardless of the sock cymbal. At the fastest tempos, it is helpful to lengthen the ground beat to a whole note rooted on beat one. (This lengthening of the ground beat at a fast tempo is comparable to a jogger pacing breaths more widely as he or she runs faster, allowing the jogger to stay relaxed and not hyperventilate. The faster a musician plays, the more he or she should relax.) Tapping feet on all four beats, perhaps even just on two, might be a laborious distraction as tempos quicken.

Illustrate the sensation of shifting ground beats at increasing tempos using Figure 4.4 If your sense of pulse seems unstable, set a metronome to match the “snapped” rhythmic pulses as you scat the cross-rhythm simultaneously. (Metronomes work just as well on beats two and four as they do on one and three, but you might want to tell your novice students that you are using a “jazz metronome”—see how long it takes for them to catch on!)

I have adjudicated bands that, when faced with a cross-rhythm, unfortunately shift the ground beat to match it or break up the ground beat into small values (eighths or quarters)—rendering the cross-rhythm effect virtually impotent. Do not deprive yourself and your students of the true sensation of playing cross-rhythms—use the longest ground beat your senses will allow.

Complex/Mixed Meters

This cross-rhythm/metronome technique can be applied to mixed meters as well: learn the passages not only in the notated meter but also over a quarter-, half-, and whole-note pulse. This superimposition over simple meters will minimize (if not eliminate) the “rushing” that is so common in mixed-meter performances: now the passage can be practiced with a basic metronome, heightening the sensation of the cross-rhythm (which is exactly how most listeners, not following scores, perceive the music):

|

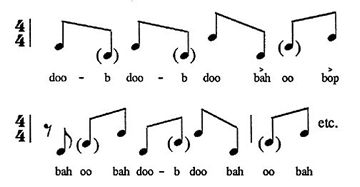

“Downbeat/Upbeat” Passages

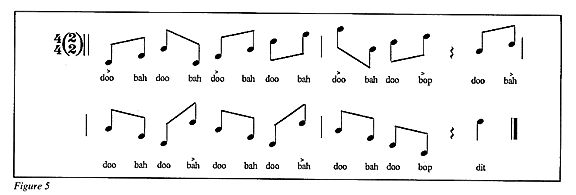

As mentioned earlier, ghosted (de-emphasized) notes are essential to proper jazz phrasing (in which all notes are not created equal.) A director or student who is inexperienced in the jazz tradition will find that recognizing which notes should be ghosted is often a challenge when the score offers no indication. I teach students to identify what I call “downbeat passages” and “upbeat passages” (both types more common at faster tempos).

A series of notes with alternating leaps at a brisk tempo, as in the following example, qualifies as a “downbeat” passage in which the downbeats are emphasized and the lower notes, by virtue of their range, become less important until the close of the phrase:

|

Had the directions of the leaps been reversed, the upbeats would have been more important. “Upbeat” passages often involve cross-rhythms in which the very syncopation of the passage obscures the downbeat pulse:

|

Most swing-style phrases written for fast tempos fall into one of these categories. The most prominent exception to this rule is the “shuffle” style, in which upbeats are heavily accented.

The faster the tempo, the more likely it is that beats one and three of a melodic line will be accented—unless the line includes a prominent change of direction (usually upward). Examine, as an illustration of this effect in both swing and Latin styles, Figure 5:5

|

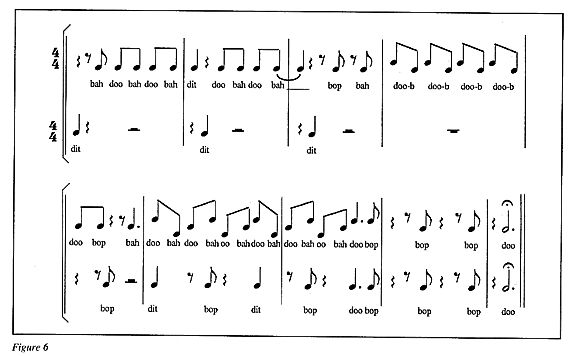

Ensemble Drill

Perhaps your band is faced with two rhythmic parts that fit together in a stop-time passage, and players have been “stepping in the holes” of the rests by mistake. Rather than waste the students’ embouchure muscles, divide the ensemble according to like rhythmic passages. Then have each division scat its part alone, in rhythmic unison, before pairing them up with the others for confidence-building. Try Figure 6, applying your knowledge of syllables, kicks, cross-rhythms, and ghosted notes:6

|

Using these techniques, you and the students in your band or chorus can develop confident, enthusiastic, and accurate swing phrasing—as soloists and as an ensemble. Coupled with a firm foundation of listening to and learning from the style of the recorded jazz masters, “pedagogical scat” can accelerate your students’ progress and teach them how to teach themselves the expressive language of jazz.

End Notes

1 “Four,” composed by Miles Davis, as recorded on Workin’ and Steamin’.

2 “Hang Time,” composed by Antonio García, as recorded on Eastman Jazz Ensemble’s Hot House.

3 “Rhythm-a-ning,” composed by Thelonious Monk, as recorded on Criss-Cross, Evidence, and Thelonious in Action.

4 “Zip City,” second chorus of Bill Watrous’ solo on Manhattan Wildlife Refuge.

5 “Sambandrea Swing,” composed by Don Menza, closing bars as played by Louie Bellson on Note Smoking.

6 “Just Friends,” composed by Klenner/Lewis, arranged by Rob McConnell, closing bars as played by Rob McConnell and the Boss Brass on Big Band Jazz.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic, chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh, Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. He has fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program, with hundreds of thousands of dollars already in hand.

A Bach/Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist, bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins: Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer, he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Mr. García is a Research Faculty member at The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Durban, South Africa) and the Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal. He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His book Cutting the Changes: Jazz Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he served as Editor of the Jazz Education Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997 Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson, “The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes: “Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s “splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing” and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and “first-class writing of special interest.” The Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely” composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

The Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute, Mr. García has adjudicated festivals and presented clinics in Canada, Europe, Australia, The Middle East, and South Africa, including creativity workshops for Motorola, Inc.’s international management executives. The partnership he created between VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz Improv; Music, Inc.; The International Musician; The Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards. Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of 434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Artsí 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service and in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame. Visit his web site at <www.garciamusic.com>.

If you entered this page via a

search engine and would like to visit more of this site,