|

This article is copyright 1999 by School Band & Orchestra and originally was published in its October and November 1999 issues in two parts. It is used by permission of the publication. Some text variations may occur between the print version and that below. All international rights remain reserved; it is not for further reproduction without written consent. |

It's About Time: Improve Your Groove

by Antonio J. García

Time-feel is perhaps the most-ignored element of musical practice. This might be particularly true in jazz practice, for the nature of time-feel is different in jazz than in many other musics.

As students of music, we tend to practice range, tone, attacks, scales, even dynamics before we work on our time. Yet what is the most-glaring error in any ensemble performance...or in any jazz solo effort? Our ears will put up with quite a few cracked notes; but a performance with poor time-feel, bad counting, or an unsatisfactory interpretation of the "groove" will quickly disenchant us.

When we do practice our time-feel, how do we do it? Do we simply listen to the constant click of a metronome and play along? Is that practicing our time—or having it already given to us?

I must emphasize that nothing replaces listening to jazz as the ultimate teaching tool. Playing along with jazz recordings is invaluable as well. However, listening and playing by themselves are not enough; for one has also to understand what s/he is hearing. We can actively explore a series of exercises to develop our time-feel. All provide group participation via counting, scatting, tapping, or clapping; and any exercises in which you might lead a smaller group of volunteers participating at the front of a rehearsal room or auditorium can be in part experienced by everyone else's feet moving in place where they are seated or standing.

Since swing feel is a greater challenge for most than even-eighth (bossa, samba, rock, etc.), we will focus on swing. However, note that these exercises can and should be applied to even-eighth explorations as well—for instrumentalists and vocalists.

Developing an Internal Beat

The best time-feel practice begins with your body alone: prove that you

have mastered the beat without the external complication of an instrument, which

can be added at the final stage of practice. The best practice is also initially

distant from any written music. When you pass on these exercises to others,

do so by the experience first: internalize the exercises and then teach

them aurally and physically, away from printed music so as to

heighten the internal growth of all concerned. Then relay the printed music

later.

To begin, set a metronome to resonate on beats two and four of a moderate 4/4 swing tempo. (This ground beat mimics a drummer's hi-hat.) Alone or with a partner, listen to the beat: match it with your finger-snaps, and then turn down the metronome's volume to an inaudible level. After a few measures, restore the volume and compare your beat to the metronome's (Ex. 1).

[NOTE: For online study, I have now added mp3 files to most of these visual examples in order to demonstrate these concepts. You'll hear the sounds of actual participants in one of my "groove" workshops corresponding to Examples 1-8, 10-18, and 20-21. To hear the audio, simply click on the Example. You may find it helpful to then drag the resulting playback window out of the visual way of the notated example so that you can see and hear at the same time.]

If they didn't match, consider a common cause: not feeling the pulse on the silent beats. By moving your forearm silently in rhythm between the metronome's pulses, most people improve their accuracy. This is the first step to internalizing the beat: physically (but silently) feeling all pulses between what the metronome provides you.

Once you are successful, add a vocal element: can you scat a passage and/or converse with someone and still match the return of the beat? This challenge mimics your rhythmic and arrhythmic solo work above the ground beat.

Let's consider a tempo twice as slow, one more appropriate to a ballad such as Neal Hefti's well-known Li'l Darlin'. Ballads provide a greater challenge than moderate tempi. Place the metronome on beats two and four; and snap your fingers in tandem (Ex. 2). Once you're "locked in," lower the volume for a few bars and restore it. If you matched, add scatting the rhythm of the first phrase of Li'l Darlin' to the exercise.

Aside from the obvious benefits of internalizing time for a soloist, the improvement is potentially greater for any ensemble. Usually a jazz band (or wind or string or vocal group of any nature) that seems sloppy in its rhythmic delivery fails these tests at the outset. But in just a few minutes of concentration, the same ensemble develops a remarkable accuracy for the beat; and when the instruments are added, the music delivery is incredibly improved. Students can continue this practice on their own as well as in the ensemble.

Jazz bands tend to rely on the drummer for the time—which means that even in a best-case drumming scenario, your band cannot perform "stop-time" passages well. The worst-case scenario is frequently heard. Everyone in the ensemble is responsible for the time. When was the last time your ensemble's time was tested?

True Time-Practice

Instead of lowering the metronome's volume to test ourselves, let's just create

more space between the pulses. Consider the pulsing to be only on beat four

of each bar (such as in a drummer's cross-stick pattern, Ex. 3). Are

you comfortable snapping two and four? If so, add some scatting or talking and

be sure you can apply such improvisation and still maintain your time-feel.

Once secure with the metronome clicking once per measure, adjust it to once every two measures (Ex. 4), four measures (Ex. 5), or eight or sixteen measures (not shown). If the metronome's click indicates you are slightly ahead of or behind the beat, immediately try to adjust your pace (without stopping) to meet the next cycle's click. It can be done!

|

Applications Given that combos also lean excessively on their drummers for the time, I then like to bring the metronome over to the bassist's ear, telling the drummer that now s/he must take the time from the bassist. For most students, this is a shocking thought: many young drummers do not pay enough attention to their bassists to collaborate effectively with them. The evolution that takes place when a drummer is forced to concede that the bassist has better time (at least while the metronome is with the bassist) is often extreme. Lastly, I move the metronome to a horn soloist's ear; for few combo members ever consider a horn player to be so responsible for the time. Yet doing this exercise for the horn player reveals how his or her indecision, ornaments, stop-time, or other factors contribute to the rushing or slowing of the group's time. Once the horn soloist is in synchronization with the metronome, I can instruct the others in the combo to take the time from the soloist—again, a notable shift that provokes interesting evolutions in the entire combo's sense of time. |

For swing, practicing with a metronome on beats two and four is a necessary initiation but limited application. True time-practice comes with matching your snapping to clicks that are widely enough spaced to allow you to err and adjust. As soon as you have grasped a given challenge, double it! I have observed students successful at a setting of two beats per minute (once every sixteen bars); and I have no doubt that some have matched one beat per minute now and then.

Once you have matched the click by snapping, add vocal scatting or conversation to the challenge. If you're still secure, it's time to bring in the instrument: practice melodies with the extended clicks. For the ultimate challenge, then practice improvising with the extended clicks. Then change the tempo to accommodate more up-tempo or down-tempo tunes (moving the ground beat to beats one and three as needed for up-tempos).

No one outgrows these exercises. I have yet to meet the musician who can repeatedly improvise music to clicks at one beat per minute, though one may exist. It seems none of us have perfect time. But those musicians who practice their time seem to be far more advanced in pulse-keeping than those who do not. And I would rather make music with the former than the latter.

Imagine the potential of an ensemble—jazz or classical—in which the members are confident in matching a pulse of even eight beats per minute. And why shouldn't they be? With this practice, it's quite possible.

Practicing "Feel"

We all know how antiseptic-sounding any attempts at jazz can be when the swing

feel is not convincing. Pulse aside, how can we best promote the growth of a

mature swing feel?

It is my opinion that the essence of a mature swing feel lies in the internalization of cross-rhythm, for this is an essential element of African and Latins musics brought to jazz. Musicians without a secure sense of cross-rhythm are ill-prepared to address the polyphonic and polyrhythmic character of jazz.

The good news is that again, much of this skill can and should be learned away from the instrument. History rumors that Duke Ellington once said he wouldn't hire anyone for his band if he thought they could not dance. I don't know if that's true; but I find that a form a cross-rhythmic marching, if not dancing, is the quickest route to maturing a swing feel in musicians not completely comfortable with the idiom.

The next group of examples are in a consistent format, to be read from the bottom up: first the movement of the "Feet," then the voices "Speak," followed last by the clapping illustrated on the "Hand" stave. Each of these staves adopts a specific role in the jazz language—though again, the exercises are completely adaptable to non-jazz musics as well. And while an individual can and should practice them alone, a group introduction serves well to illustrate their ensemble application and importance. First do the exercises without accompaniment; we'll discuss other options later.

|

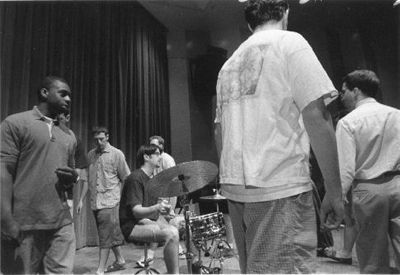

The class speaks swing eighth-note cross-rhythms while walking in half-notes (feet landing on beats two and four) around the drummer's swing groove. Photo credit: Jacob Fries,

courtesy Pick-Staiger/ |

Feet First

Assemble the group (without instruments) in a circle, facing heads to backs.

Call out "left" and "right" small steps to get the group in slight motion at

medium tempo; and by adding your quarter-note count of "1 2 3 4," establish

that the feet are moving not on beats one and three but on two and four (the

ground beat of medium swing, Ex. 6, bottom stave). Tip:

Persons having trouble keeping in step generally do better when instructed to

lift their feet in the rhythm of beats one and three, thus internalizing the

beat further.

Speak the Divisions

Once the group is stable in its walk in time, speak in groups of three swing

eighths, slightly accenting the first of each three eighth notes (Ex. 6,

middle stave). Ask everyone to join in.

|

Doing the Math Thus for 4/4 time, 128 divided in half yields 64, on to 32 and so on, down to 2 beats or 1 beat per minute. And 192 yields 96, on to 48 and so on, down to 3 beats per minute. For 3/4 time, dotted-half = 54, divided by 3 yields 18, 6, and finally 2; and 81 yields 27, 9, and finally 3. While not all of the exercises provided need to be done with a metronome, I have given each a tempo marking allowing for that divisible potential. Technology Now anyone with computer-notated performance or sequencing capabilities can create a file generating pulses such as those required for these exercises. The result can be left on the computer or dubbed onto tapes for convenient practice by any individual or ensemble. I have searched many wholesale and retail outlets for a metronome that goes to 8 or less beats per minute and have not found one below 30 beats in any catalog or store. If you find one, please contact me and let me know. The device I am using in this presentation is made and sold by an individual, Jon Parkes, an oboist with the Rochester (NY) Philharmonic and engineer in his own business. His current model offers 1 to 999 beats per minute, an audible internal speaker, a headphone jack, crystal-driven accuracy, optional exact start-stop buttons, optional accents on given beats (every second beat up to every ninth beat), and runs on a nine-volt battery. The price ranges from $125 and up and comes with a lifetime guarantee—his lifetime. A brochure is available, if you wish; contact: Jon Parkes, 2 Highland Heights,

Rochester, NY 14618 USA At last conversation, he also had a few models in stock of the variety I possess, which provides a click-track generator (in eighths of frames) for film-scoring in addition to the metronomic functions. Tell him I sent you...but I don't get a commission! |

It is common for some in the group to lose their rhythmic step of half notes when asked to count these eighths in cross-rhythms of three—just as it is common for young soloists and ensemble-members to lose their place in the beat when performing such cross-rhythms. Tip: While continuing the group's footsteps, tacet the voices and allow those lost to catch up. Then reinstate the speaking in cross-rhythm. Depending on the group, several attempts may be needed before most reach the goal. But even those who experience it for only a few moments understand the goal and the method far better than those who have only attempted to accomplish cross-rhythming on their instruments!

Adding Hands

The top layer to add is clapping on the first eighth of each cross-rhythm spoken:

thus clapping when saying "1" (Ex. 6, top stave). Begin with feet only,

then adding the spoken eighths, and then finally the clapping.

Again, it is common for some in any group to falter. Tip: Just as someone who learns how to juggle three balls in the air can learn to juggle four, students can learn to master this additional challenge. While continuing the group's footsteps, tacet the voices and clapping and allow those lost to catch up. Then reinstate the speaking in cross-rhythm...and then the clapping.

Frequently students clap loudly and let their voices diminish as they focus on this new element, but this is an unsatisfactory result. Elements must be felt equally so as to develop a polyrhythmic sense: excluding one element for another does not bring a mature swing feel. Tip: Encourage the students to clap at a more moderate volume and maintain their vocal strength. As a gesture of this "Jazz Boot Camp," a simple call from you of "I Can't Hear You!" might make them more self-aware of the imbalance.

A common trait of those still faltering is that their clapping occurs as an abrupt gesture: a quick motion intended to catch the proper moment. Tip: The solution is simply to demonstrate and encourage a circular motion by the hands in front of the body, towards and away from the point of the hands' meeting. Performing this circular motion with the hands promotes persons' physically feeling the cross-rhythm in a cycle of time, not as individual moments to be counted separately—a necessary skill in performing cross-rhythms. (This is why the top staves of these examples show rests in eighths rather than using any quarters: the passages are to be felt as repetitive cycles, not counted.)

|

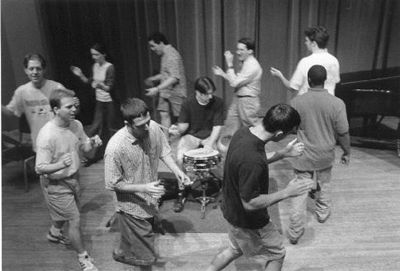

Adding a clap on the first eighth of each cross-rhythm, the "march" continues around the drummer, who cross-sticks the snare rim simultaneous to the others' claps. Photo credit: Jacob Fries,

courtesy Pick-Staiger/ |

Widening the Cross-Rhythm

Once "3's" are relatively stable, it's probably time to pause and reverse the

direction of the circle: no need for anyone to get dizzy! And then enlarge the

cross-rhythm from 3's to 5's (Ex. 7), again starting from the bottom

stave and working upwards. Participants will need to describe a wider circle

with their hands, still larger when the exercise expands to 6's (not shown)—which

feels relaxing because it's simply two groups of the 3's already accomplished.

Experiencing 7's (Ex. 8) calls for a change in the speaking, as the two syllables of the word "seven" would create an unwanted total of eight eighths. Tip: I find the sole use of the syllable "sev" to be an excellent substitute—and the participants' hands circle wider than ever as everyone feels the cross-rhythm in the cycle of time.

Other Meters...& Abakwa!

The cross-rhythming sensation is not exclusive to 4/4 time: any meter can include

cross-rhythms. A prime example is 3/4 time. Coordinate the feet to step in time

with dotted half-notes, the ground beat of a medium-tempo jazz waltz (Ex.

9). Speaking four eighths in swing over the 3/4 time yields a common cross-rhythm:

4's over 3—accentuated by clapping on the first eighth of each pattern.

[NOTE: No audio is linked to the following example.]

The 12/8 meter—four beats each divided into three eighths—provides an additional and important potential for 4's over 3. Step your feet into a dotted-quarter pulse (Ex. 10, bottom stave); then speak a cycle of three eighths and an eighth rest (middle stave). With the downbeat of beat four accented (rather than simply the entrance of the final cross-rhythm), you have created the abakwa beat, crucial to Afro-Cuban jazz and originally performed only by the members of a secret society of Cuban males. (For just one prominent example of the abakwa beat in Afro-Cuban jazz, listen closely to the interludes of Dizzy Gillespie's composition, Kush.)

Plan the clapping also to accent the start of the first two cross-rhythms, plus the last downbeat (top stave); and you have performed half of the clave rhythm inherent to much Afro-Cuban jazz.

A most-interesting feel occurs when you shift the feet to move only on beats two and four (Ex. 11) while maintaining the voice and hands as previous: the feel much more closely resembles swing—a demonstration of how crucial the abakwa beat and the concepts of cross-rhythm are to a mature sense of swing.

Clave & Streetbeat

The historical links between musics become even clearer when one explores a

full "3-2 son clave" beat. Move your feet in half notes in a moderate cut time

(quasi bossa or samba, Ex. 12); speak in imitation of a drummer's clave

cross-stick pattern (middle stave), and clap as indicated to match a full clave

beat. This sense of creating and interrupting a cross-rhythm is crucial to the

success of any soloist or ensemble in the idiom.

Now swing the eighth notes and move your feet on beats two and four (Ex. 13). You are now creating a "New Orleans Streetbeat," built on the same clave pattern and experienced by any New Orleans high school marching band student as the primary cadence for Mardi Gras parades. With the harmonic, melodic, and formal roots of Dixieland, the Latin music influence of the nearby Caribbean, and the swing nurtured by cross-rhythming streetbeats, it is no wonder that so many young jazz artists emerge from this one city.

|

Accompaniments

|

Informed Swing

You are now ready to unite your knowledge of ground beat, cross-rhythm, and

abakwa with an element singularly swing-flavored: the walking bass-line. Placing

your feet in a two and four pulse (Ex. 14, bottom stave), transfer the

abakwa beat to tapping on your chest while reciting the word "abakwa" (top stave).

Have someone in the room improvise a simple walking bass-line, such as on F

blues, on bass or piano: it typically falls on all downbeat notes. Notice how

the knowledge of the abakwa beat assists the best placement of the bass' downbeats (though the line in the example is far more syncopated).

Then try shifting the attacks of the bass-line one eighth to either side of the downbeat, such as seen in Ex. 14. Though not cross-rhythms, these placements are derived from cross-rhythms; and they accentuate the sense of swing feel. If one translates the entire exercise to 4/4 meter (Ex. 15), the effect is just as striking. This is not to say that swing bass-lines should all be moved off of the downbeats: a knowledge of the abakwa beat can improve the swing feel of even non-syncopated quarter notes! Similarly, it affects how a drummer plays time, how a pianist or guitarist "comps," and how any soloist places his or her notes; for any soloist must be able to divide beats not only into triplets and even-eighths but also into straight-sixteenths and swing-sixteenths.

Adding Pitch, Instruments

All the growth so far has taken place without the use of melodies; so the next

step is to add pitches to our cross-rhythming—but first without instruments.

Let's take the medium swing we marched to in Ex. 6 and replace the spoken

numbers with sung numbers (Ex. 16). You can retain the accenting

clap of Ex. 6 as transition, if you like. Melody makes the cross-rhythming

sensation all the more musical, after which it's finally time to transfer the

pitches to instruments without singing—but still marching in the circle.

(Pianists, acoustic bassists, mallet percussionists, and the like can leave

the circle to go to their instruments; guitarists and electric bassists can

remain in the circle.)

|

Having already sung melodic cross-rhythms while in step with the drummer, the class now plays the melodic cross-rhythms while "marching" (the author in foreground). Photo credit: Jacob Fries,

courtesy Pick-Staiger/ |

Similarly, the exercises of singing and performing pitches in cross-rhythm can be expanded to 5's over 4/4 (Ex. 17), 6's (not shown), or 7's (Ex. 18)—or altered to accommodate the other meters of 3/4 (Ex. 19), 12/8 abakwa rooted on downbeats (Ex. 20), 12/8 abakwa rooted on beats two and four (Ex. 21), or any other combination you might imagine. Once you've mastered these, there are more challenges ahead: try accenting the second note of each cross-rhythm...then the third...and so on!

[NOTE: No audio is linked tp the following example.]

Swing Eighths—A Definition

Defining the eighth-note feel of swing is a challenge. It's not exactly a triplet

feel, and it's certainly not a straight-eighth feel. In many ways, it is difficult

to define it any better than simply listening to a Louis Armstrong recording.

Yet when I require my own students to demonstrate that they have a grasp on

a mature swing feel, this means they must show that they can play eighth

notes informed by the traditions of cross-rhythm and influenced by the abakwa

beat. This amplifies their understanding of these essential elements of

African and Latin musics and promotes a mature swing feel born of jazz history

itself.

|

Additional Resources

|

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic, chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh, Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. He has fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program, with hundreds of thousands of dollars already in hand.

A Bach/Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist, bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins: Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer, he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Mr. García is a Research Faculty member at The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Durban, South Africa) and the Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal. He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His book Cutting the Changes: Jazz Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he served as Editor of the Jazz Education Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997 Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson, “The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes: “Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s “splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing” and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and “first-class writing of special interest.” The Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely” composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

The Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute, Mr. García has adjudicated festivals and presented clinics in Canada, Europe, Australia, The Middle East, and South Africa, including creativity workshops for Motorola, Inc.’s international management executives. The partnership he created between VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz Improv; Music, Inc.; The International Musician; The Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards. Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of 434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Artsí 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service and in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame. Visit his web site at <www.garciamusic.com>.

If you entered this page via a search

engine and would like to visit more of this site,

For further information on School

Band and Orchestra, as well as on the resources referenced above, see