|

Antonio García performing on tenor trombone, bass trombone, piano, percussion, and vocals. |

|

This article is copyright 2021 by Antonio J. García and originally was published in Down Beat, Vol. 88, No. 10, October 2021. It is used by permission of the author and, as needed, the publication. Some text variations may occur between the print version and that below. All international rights remain reserved; it is not for further reproduction without written consent. |

The Importance of Beat 4

Masterclass

by Antonio J. García

|

Antonio García performing on tenor trombone, bass trombone, piano, percussion, and vocals. |

In school and on the bandstand I learned that accenting beats two and four brings out a medium-swing groove. And a decade or so after graduating with my degrees, I truly understood the importance of beat eight in the 2-3 or 3-2 clave of an Afro-Cuban son montuno—even though I’d been hearing it in the streetbeats of my native New Orleans as long as I can remember. Understanding an idea doesn’t mean you can apply it, and I’d estimate it took me yet another decade to infuse the above deeply into my performing and composing.

As an educator, I continually look for ways to highlight for my own students the importance of beat four when improvising in medium-swing style. Not long ago two of my Jazz Theory students each brought in a master solo that as a pair screamed “beat four!” in a way that even the two solos separately could not. So even though I’d known these recordings for many years, the proximity of my students’ study of them allowed me to spotlight beat four in a very pronounced, impactful way. Thus the teacher becomes student—part of the joy of my learning process.

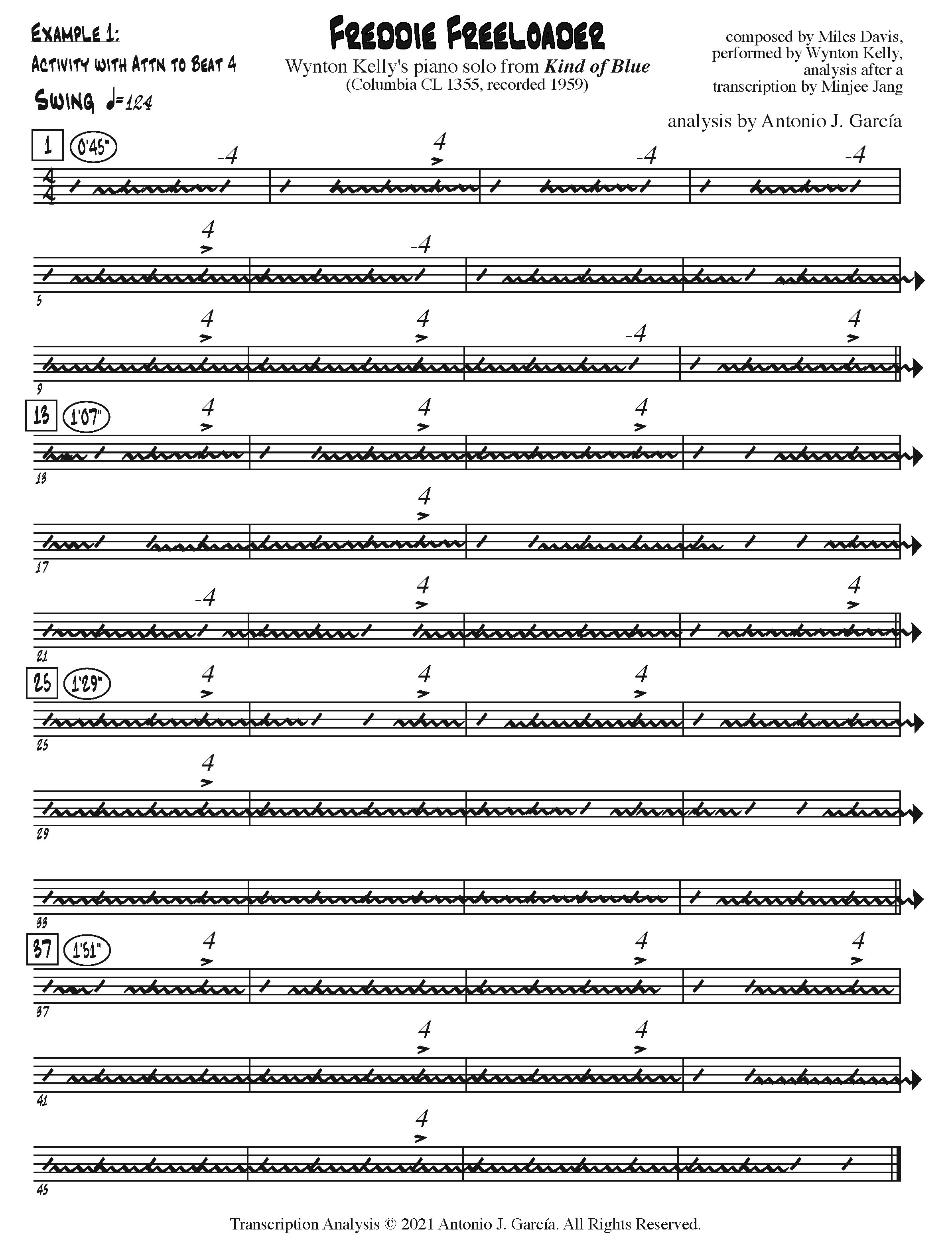

Wynton Kelly’s “Freddie Freeloader” Solo (Please pardon any ads preceding the linked recording.)

Revisiting this Example 1 1959 Kind of Blue track (Columbia CL 1355) when Minjee Jang brought it into class, I realized that from mm. 2-29 Kelly makes a point of hitting his highest or lowest and/or ending phrase-note on beat four some 15 times. This is not coincidence: it is a crucial element of why his solo swings so hard: he emphasizes the most important beat in 4/4 medium swing. And another five times in the first 11 bars Kelly cuts off on beat four, placing the accent of “negative space” to allow bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb to punch the groove through all the more clearly.

So ask yourself:

“How often do I do that in a solo? How often do I place my highest or lowest

note on an accented beat four? How often do I continue a 3/4 cross-rhythm on an

accented beat four? How often do I end my phrase on an accented beat four—or on

an accented rest on beat four?” If your answer is “hardly ever,” take

this element into the practice room; master it; make it your own as you

improvise slowly—because in 48 bars Wynton Kelly is revealing to you 27 times how

to groove hard in your solo. It’s not the only way to swing, but it’s one great

way!

|

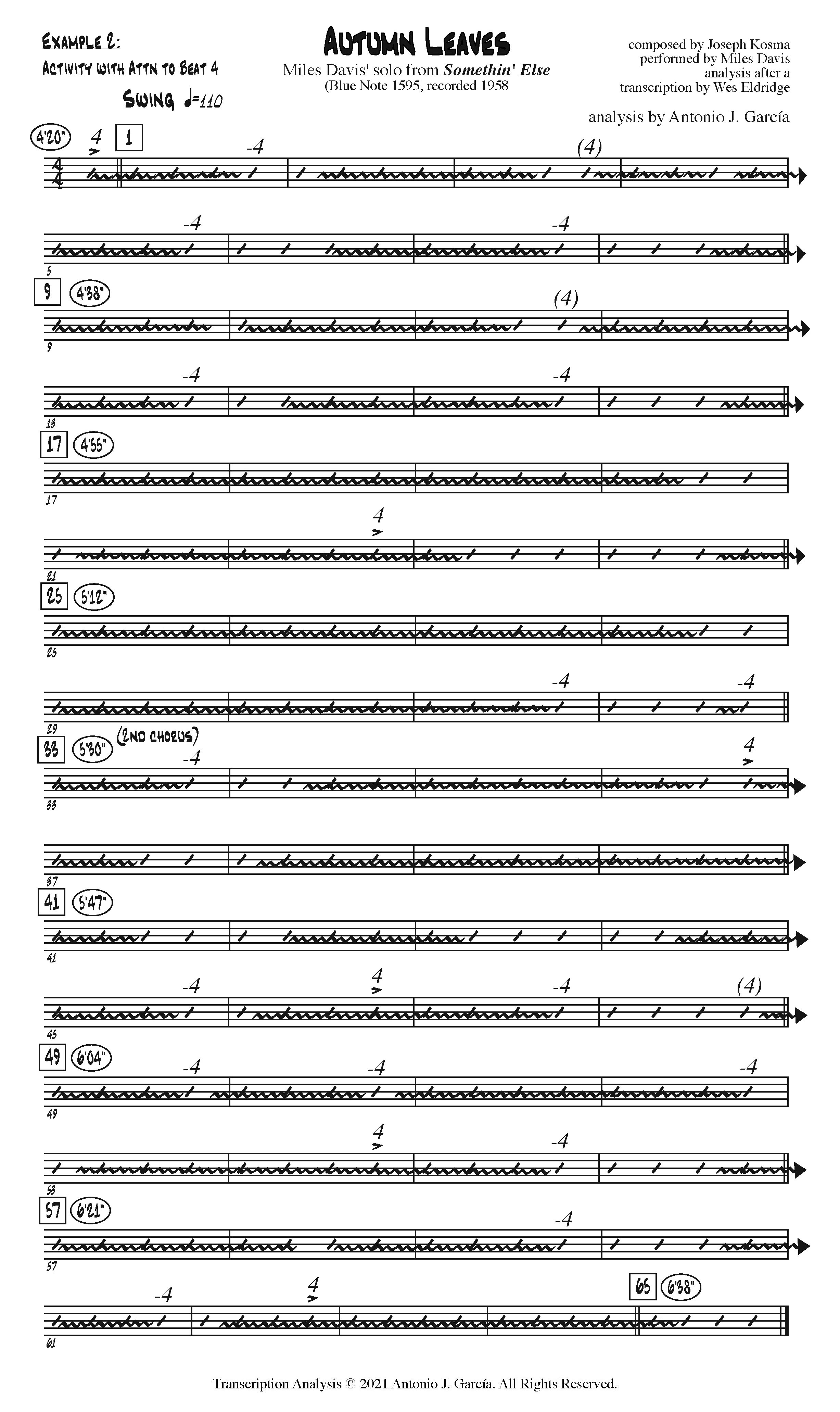

Miles Davis’ “Autumn Leaves” Solo (Please pardon any ads preceding the linked recording.)

A listen in proximity of Kelly’s solo to this Example 2 1958 Somethin’ Else track (Blue Note 1595) that Wes Eldridge brought into class really highlighted the impact of “negative space” on beat four in medium swing. How often does Miles not play on beat four during the first 15 bars of his solo? Seven times: seven opportunities to allow the rhythm section to influence and complement his groove. This is something you can practice and put in your expressive toolbox.

Sometimes, as in m. 1, he releases a longer note into silence on the downbeat of four in order to have his tongue-stopped release create that impact of “negative space” on beat four. Other times, such as in m. 3, he uses a silent beat four as an accented springboard for the rhythms that follow. In all, Miles is more about not playing on beat four than accenting it with a pitch: 16 times within 64 bars he shows us that mastering medium swing can often be about what you don’t play on the swingingest beat of the bar.

He also makes a point of repeating his phrasings in ways less-experienced musicians might not. For example, compare the timing of parallel locales within his first and then second chorus of soloing: the pickup and first phrase of mm. 1 and 33, also 13-15 and 45-47, are quite the match; yet more are similar. Throughout the many phases of his career, Miles showed us that it’s not about coming up with constantly new melodic ideas: it’s about expressing your ideas well.

|

Jazz Practical

From day one I tell my students we’re not in Jazz Theory class: it’s Jazz Practical class. Every concept we explore is then to take into the practice room and composing/arranging studio so as to make it part of our toolbox of expressive options. Thanks again to VCU students Minjee Jang and Wes Eldridge for bringing me two long-familiar solos that together made a stronger case for our communicating the importance of beat four in medium swing.

There are so many ways to learn from the masters’ solos without notating a single pitch or chord. What about the soloist’s tone quality, articulation, dynamics, pace, direction, tone, thematic development, and quoting? What about the interaction between soloist and rhythm section, or borrowing from different rhythmic styles? What about stealing ideas from the preceding soloist? These elements draw our ears again and again to great solos. Check out the 14 different ways I analyze two choruses of trombonist Steve Turre’s solo on the tune “Stompin’ at the Savoy” from his CD “TNT” (Telarc CD-83529). It’s an inspirational solo well worthy of examination: see my analysis “Transcribing Jazz Solos without Pitches."

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic, chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh, Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. He has fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program, with hundreds of thousands of dollars already in hand.

A Bach/Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist, bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins: Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer, he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Mr. García is a Research Faculty member at The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Durban, South Africa) and the Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal. He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His book Cutting the Changes: Jazz Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he served as Editor of the Jazz Education Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997 Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson, “The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes: “Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s “splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing” and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and “first-class writing of special interest.” The Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely” composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

The Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute, Mr. García has adjudicated festivals and presented clinics in Canada, Europe, Australia, The Middle East, and South Africa, including creativity workshops for Motorola, Inc.’s international management executives. The partnership he created between VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz Improv; Music, Inc.; The International Musician; The Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards. Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of 434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Artsí 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service and in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame. Visit his web site at <www.garciamusic.com>.

If you entered this page via a

search engine and would like to visit more of this site,