Alex Iles: In the Moment

Michael Davis

transcribed by Ben Culver

|

all photo credits: courtesy Alex Iles |

Associate Jazz Editor’s Note: Trombonist Michael Davis has for years hosted his Bone2Pick interview series, exploring the careers and advice of acclaimed trombonists and other musicians. I asked Michael if the Journal could mine one of the interviews for our readers, and he kindly agreed. Check out the Bone2Pick video series archived at <www.hip-bonemusic.com/blogs/bone2pick>! —Antonio J. García

The trombone section for a Pat Metheny recording at Sony Studios: Steve Holtman, Alex Iles, Pat Metheny, and Bill Reichenbach. |

|

Michael Davis: I am really excited to have an opportunity to showcase one of the most successful, one of the finest trombone-players in the Los Angeles area, the great Alex Iles. Alex’s myriad performance and recording credits include Joe Cocker, Prince, Harry Connick, Jr., the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, Terence Blanchard, Henry Mancini, John Williams, and Ray Charles, just to name a few. He’s toured with the late great Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman; he’s been in the orchestra for the Academy Awards, the Emmy Awards, the Golden Globe Awards, and the People’s Choice Awards. He has hundreds of motion-picture soundtrack credits including The Incredibles, Star Wars, Polar Express, National Treasure, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Spiderman.

He’s one of the most versatile brass-players anywhere in the world: the principal trombonist of the Long Beach Symphony, he’s also performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic as well as the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. He is the trombone and jazz instructor at the California Institute of the Arts and Azusa Pacific University. And, to go way back, we were both members of the 1979 California All-State Symphonic Band! More recently, I’m really thrilled that he was willing to add his talents to a project of mine that I did a few years back called Absolute Trombone II; and his brilliant playing came through on that.

Early Training

|

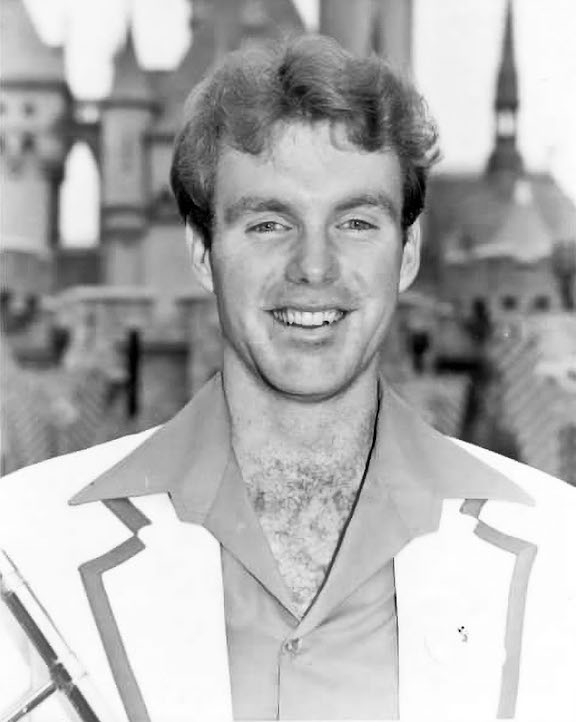

Disneyland All-American |

MD: Let’s talk about your background. I know you’re a SoCal guy: how did you end up on the trombone?

AI: We had a really great public school music program in Arcadia, California, just a few miles east of here. When my mom interviewed the orchestra director there to find out what instrument I was going to play, the interview was very quick, though I had three or four instruments in mind. He said to her, “Tell me about your son”; and my mom replied “Well, he’s very tall.” And then the director said, “He’ll play trombone.” That was it! It was chosen just based on that: long arms.

I played all the way through public school; but I didn’t take it too seriously: I was really active in sports and other stuff when I was young. By the time I got into junior high, though, I took some lessons one summer with a guy who was a few years ahead of me in high school, Jim Feichmann. We’re still in touch! One day, he brought over some J.J. Johnson, Urbie Green, and Bill Watrous records; and I had never heard anything like that before. That was the fork in the road: I was really into trombone after that. I was about 13 years old and started practicing a little bit more; and by the time I got into high school, I was playing a lot and was thinking about maybe pursuing music at a higher level.

But I wanted to have a bit more of an all-around background to my education; and my parents encouraged that, too; so to keep my options open I decided to go to UCLA and study economics in school. I knew I wanted to play music; but when I looked at all the majors, including music, they all had a lot of upper-division required courses—except economics, which had the fewest number. So I could play all I wanted yet get a non-music degree in four years.

It turned out to be a really good program. I learned a lot about economics and business; and I was able to take a lot of English courses, took a one-year-long writing and editing course, and even did an internship doing research and script-editing for a TV production company. So much of this experience eventually related to what I later did in my music career; so school was a really great experience for me. I spent a summer playing in the Disneyland All-American College Band out here, and that really got me excited about music. Even though I was not a music major, I took a theory course and went to the Aspen School of Music a couple of summers: that’s where I studied with Per Brevig and Ron Borror.

With |

|

I started

studying weekly with Roy Main, who turned into my primary teacher. He was

fantastic. Most of his students were freelance players doing shows and

recordings: Alan Kaplan, Bob McChesney, Andy Martin, and bass trombonist Bob

Sanders. So he really helped me get more established in professional

working situations.

By the time I got out of school, I was kind of torn about what to do. I was working an insurance job for a while, also in a music publishing company. But then I got a call to work on a cruise ship for three months; and I did that, learning how to play club dates and casuals. That was a really great experience.

Then one of my old friends from when I was on the Disney All-American College Band, Dan Levine, mentioned that Maynard Ferguson was looking for a trombonist. So I sent in a demo tape to Steve Weist, who was the lone trombonist in the horn section at the time; and he handed it to Maynard. They invited me out to do a tour with Maynard about 1985. That’s when I started doing things professionally. When I came back into town after that I had some credit so was able to work a little bit, and that’s how I got started.

MD: I think it’s always interesting how, especially for guys our age, that big-band experience was so vital to development: just playing every night and being in that kind of intense environment. It’s unfortunate it’s not up for the taking anymore.

|

Maynard Ferguson's horn section, 1986: Alan Wise, Maynard Ferguson, Wayne Bergeron, Alex Iles, Tim Ries, and Rick Margitza. |

AI: It’s really sad. That’s such an important experience to have: when you’ve been travelling all day or you’re not feeling great, but you still have to bring it to the performance that night. I’m sure you’ve had those nights with Buddy’s band and touring with the Stones, and there’s nothing else like that. It goes beyond your abilities on the instrument and your musicianship, and it helps you develop the perseverance you need as a professional. It’s really important.

Versatility

MD: What is your approach to being so versatile? You’ve played with the L.A. Philharmonic, Maynard Ferguson’s band, all the motion-picture work: how did that evolve for you?

AI: It’s interesting: I think most trombone players, when they’re starting out, are doing a lot of different kinds of music. Joe Alessi says some of his fondest memories in high school are playing in the Monterey All-Star Jazz Band. People sometimes forget that when coming up he had an experience in a lot of ways the same as you and I had.

And I think I didn’t ever fully grow into a specific kind of trombone player. Whereas some people started to have a specific plan or goal in mind, my goals were a little bit more diffused: I took a survey approach to everything. I would always try to do what I needed to do to participate at that moment. So I had to learn how to play New Orleans style music: that’s not something that came naturally to me. I really put a lot of time into that for a short period so that I could learn enough songs to accept a call for that. Same thing with a lot of other kinds of music: I tried to learn from the people that were doing it right so I’d be able to participate and find a way to express myself in that genre.

Session with Michel Legrand: Alex Iles, Bill Watrous, Michel Legrand, Bill Reichenbach, Alan Kaplan, and Andy Martin. |

|

There are so many things in different genres of music that overlap. One of my beliefs is that the skillsets I need to play certain kinds of classical orchestral music draw on my experience having played in jazz bands. If I’m playing Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or The Firebird, or Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin, there’s every bit as much rhythmically and intensity wise in the brass section playing those pieces as with the feeling you have in a brass section playing in a big band. I learned a lot playing Bordogni etudes, but they don’t necessarily translate into playing Stravinsky.

So it’s important to bring to other places the experience from whatever musical thing you’re already doing. Different music simply emphasizes certain qualities and skillsets. So develop all your skillsets together; listen and be familiar with the kind of music you want to play; and then you can work on projecting that out. I always feel like I’m maybe, at my best, 80% of the player I could be in a given genre. I know there’s someone way better than me at that genre, but I’m just trying to hang with them. The best you can hope for sometimes is: “Well, he was there, too!” And that’s fine!

MD: Well, I think you bring much more than that. You

Listening

MD: You know you said something I think is really key. Every time we’ve played together, you’re one of the great listeners. You’re always adjusting to what’s going on; and I think that’s part of the key to your success, whatever genre you’re in.

AI: Thanks: I’m first and foremost a listener of music. In certain situations, I love listening to music as much as I love playing. I’ve had amazing experiences sitting in an audience and listening to music. When I was 14 or 15 years old, my friends and I would pile in the car and go over to Eagle Rock High School, pay three bucks, and go listen to the jam sessions there the last Sunday of every month. After the amazing high school band played, there was a fantastic jam session featuring many of the premier L.A. jazz and studio musicians. Very often it was players like Blue Mitchell, Frank Rosolino, Plas Johnson, Jack Sheldon, Ray Brown, or Shelly Manne. I have vivid memories of that experience, even though I had no idea what they were doing; but it was so great, and they were all having so much fun.

|

Performing on-screen with the "Planetary Union Symphony" on the TV show, "The Orville." The latex make-up took three hours to put on! |

Motion Picture Industry

MD: A lot of people know you from your work in the motion picture industry: your list of credits is beyond impressive. How do you approach that kind of work?

AI: Most of the time when we go to work we’re not quite sure what we’re going to do. Sometimes the contractor has sent out files ahead of time with some music; but to be honest, a lot of us don’t look at that music too closely. We’ll just look through it quickly to see if there’s anything really crazy.

But there are certain constants: playing with a good sound, playing with good time and the click track, being in tune with a good sound, good rhythm. Stylistically there are some variants: sometimes we’ll look at a part and don’t know if it’s more of an orchestral kind of sound or more of rock-and-roll. The same group of people in the same room have to draw on the right skillset for that moment. Everything we do is tied to the picture; so you have to have an awareness of that. But most of the trombone players carry a small tenor, a big tenor, and a bass. A lot of the time if you’re called to play tenor, you’re going to play bass: it’s just the way it works out.

MD: So even if the call doesn’t call for it, you still have all three?

AI: Yeah, because sometimes they might write parts that are low: low Cs or Ds and lots of pedal tones. It really does get them the sound if they have four or five of us on bass trombones. In a four-person trombone section, that third chair is the real hairy one: you’re going to be going between bass and tenor a lot, even in one cue. Bass trombone is a really important part of studio work.

"This day was fairly unusual. There was an animated elephant character in the scene, and they wanted some music with an appropriate ‘voice.’ I tried small tenor, bass, alto, bass trumpet, euphonium, and alto sackbut. I think they wound up using the alto trombone!" |

|

“A Trombonist” vs. “The Trombonist”

AI: I have to say that I’ve never set out in my mind to be a studio trombonist: I’m always striving to be a better and more expressive musician and trombonist—and be the trombonist for that moment if I could. I like to define for students exploring freelance-playing that there are times when you have to be simply a trombonist, where you basically show up and fit in. If it’s a big band section, and you’re playing third, you’ve got to be able to do that. You’re just a trombonist that they need right then. If they need you to play in a Latin band, you gotta’ be a trombonist who can do that at the last minute. The trombonist they already had is sick or something, and they just need a trombonist. If you wanna’ be a freelance-player, you gotta’ understand that role.

Then there are other times when you’re the trombonist, where you’re maybe the first one they think of; and that might involve some solo-playing or a specific genre you’ve proven yourself comfortable with.

Sometimes,

you’re just a bass trombonist. I don’t like the word “double” because I

figure that’s an apology for less-than-better playing, and that keeps me from

being better on the instrument. As soon as I stopped thinking of myself as a

doubler, my bass trombone-playing got more serious. I’d rather be a lame bass

trombonist than say I’m a doubling bass trombonist. Any time I get called to

play bass trombone, I get compared to who does that full-time:

maybe to Bill Reichenbach. So I gotta’ be sure my standard of bass trombone-playing

is more than OK.

Since ninth or tenth grade I was playing a lot of large-bore and small-bore tenor: for me, that wasn’t hard. Bass trombone took me a lot longer. I was a little resistant at first but love it now. I even used it when I played on a guest-solo gig with a local jazz band, playing one tune on bass trombone, which was really fun. That was the first time I had done that.

MD: You know that’s a great way to define it. Sometimes you’re “a trombonist” and other times you’re “the trombonist.” I haven’t heard anyone say that: it’s a really helpful way to look at it.

AI: It's especially helpful for freelance-players. Some people get upset that they're always a sub. I love it: I'd say still a big percentage of my work is subbing for someone else.

|

Los Angeles Philharmonic |

Subbing with the L.A. Phil

AI: I was playing a job out in Palm Desert with a little show orchestra, doing a 95th birthday tribute to Carol Channing, playing all these acts and play-ons and play-offs; and I got a phone call from the manager of the L.A. Philharmonic. He explained sadly that the mother of Jim Miller (the associate principal with the L.A. Phil) was very ill; so Jim got called out of town at the very last minute. They had a concert the next day, Sunday.

So I drove back early and was thrown in to play second trombone on Mahler Symphony No. 3 with the L.A. Phil after they’d been preparing it all week and were getting ready to perform it on tour. And the other added freak-out part of it was that Jörgen van Rijen was playing principal and was going to be with the orchestra on tour. He was playing the big solo yet had to show up early and help me, a half hour before the concert, to show me how everything worked. And he was great: it made a huge difference. And he sounded so amazing on the solo: it was life-changing getting to sit right next to him and hear him play it. It was like a concert, a private lesson, and masterclass all rolled into one!

The biggest compliment I received was from someone I knew in the violin section who came up to me a few days later and said: “Hey, I heard you were with the orchestra: I didn’t even know you were there.” And I said, “I did my job.” As a second trombonist, that’s one of the highest compliments you can get.

MD: That is such an amazing story.

|

Other Types of Recording Work

MD: There’s no question that L.A. is the recording center of cities in the U.S., certainly more so than in New York. I suppose Nashville would be another one in a different kind of way. Talk about the other types of recording you end up doing.

AI: Television and film are the two main things that musicians are active in if they’re doing recording. But tomorrow, for instance, we’re doing music that you would hear on a ride at a theme park: here we record a lot of that music for Tokyo Disneyland, Walt Disney World, or any other theme parks that have music. They very often hire a big orchestra, and some of that music is the most fun to play and record. So we have two days of that coming up; that’s a whole avenue of music that a lot of people are employed doing. Real human beings are playing that music when you go on a ride!

There’s also live television out here, to an extent. In the old days, in the ’60s and ’70s, there were live variety shows, such as Flip Wilson’s and Mike Douglas’, all over the country with live bands; and there were 10 to 15 live orchestras doing live TV every week in Los Angeles. It was an amazing time to think back to. That’s changed a lot, but there’s still a fair amount of recording in other areas. Some jingle-work comes up: we did a few Super Bowl commercials here with a big orchestra. A few jingle houses still do things here. We have had some videogame work here, and I’m hoping that in the future more of that will be happening. They love big orchestras in videogame music, and so much of it has been recorded in other places besides Los Angeles; so maybe we can work more of that stuff out in the future. I’m hopeful that especially for the next generation of players coming up, recording videogames will be a big thing for them to get to do so as to build some experience.

Opportunities for Younger Players

AI: In general, it’s very difficult right now for younger players who are interested in freelancing. There used to be a big variety of things that you could do that was between sitting at home and working at Sony with Hans Zimmer. I did all that stuff: I played Chinese funerals downtown; I wore funny clothes at theme parks; I did many different odd little jobs you could get called for at the drop of a hat to play, earn your money, get paid, and go home. So much of that has now dried up for so many of the younger players. I see more of them creating their own opportunities, which is great; but still that fruitful work which had been around more for freelancers, whether recorded or live, is difficult to tap into.

|

A John Williams' Star Wars low brass section: Alex Iles, Bill Booth (principal), Phil Keen, Bill Reichenbach, and Doug Tornquist. |

I’m hoping that there will be more opportunities for the kinds of recording that younger players could get more involved within a big orchestra, where they get that experience. It has to be here, somewhere. If people are not up and ready for that experience, they’re not going to be trained; and they’ll have fewer opportunities. We’ve been really lucky that in 1977 Star Wars put the orchestra back in people’s heads. It had really been falling out of favor, as good as gone. John Williams and Star Wars created whole careers for a lot of studio musicians and composers who’ve been riding that wave for a long time. To this day, it’s still really great; but it’s a very small group of people that are able to do most of that work that comes in.

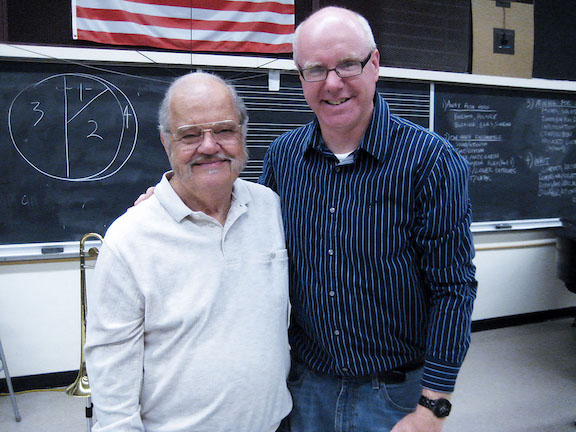

Charlie Loper

AI: I was very fortunate: I had 15 years playing second trombone in Bob Florence’s band with a great group of people. I really loved it: it was a very familial feeling. It was really great having a wonderful experience every week playing all of Bob’s charts. And the best thing was a 15-year mentorship with Charlie Loper, who to my ears is still the greatest lead trombone player I’ve ever sat next to. He just has this incredible gift of sound, phrasing, and feel; and he could lead the band from the lead trombone chair without playing loud. He has plenty of power and strength when he wants to turn it on, but Charlie just had this way of phrasing things that I’ve seen in very few other players; and everyone would just go with him. Even the lead trumpet player would just go: “Yeah, that’s it.”

He was made for that lead trombone chair, and it was always just so easy to play with him. There wasn’t a lot of soli work; but when there were four bars of something to do, Charlie would just raise the band to the max. So I really learned a lot playing with him and from his attitude: he is a very generous gentleman, a very positive person, and was always very gracious in the way he played in that band. He is very clear in the way he wants things phrased. He doesn’t say much, but he would demonstrate; and if you didn’t hear it, you were not paying attention. If I’m at all comfortable playing lead trombone, it’s largely due to sitting next to him, playing on that band.

Leading a masterclass at the American Trombone Workshop. |

|

Teaching

MD: Let’s shift gears a little bit and talk about your work as an educator. I feel like I get so much out of going to your masterclasses. You’ve got a great approach: very meaty, but focused and digestible—all the things you want to get from an educator. Tell me about your interest in teaching here in Southern California.

AI: I started getting interested in teaching in high school, when I was a section leader in the high school band and also conducted the pep band. I started getting comfortable talking to people about music, though I didn’t know what I was talking about early on. I taught through most of college, teaching a lot of the students who were taking instrumental methods, as the music education students had to learn brass instruments. I got really good at teaching clarinet players how to make a trombone embouchure: that was fun. Teaching privately had always been a part of my life.

I’d say I got more focused on teaching clinics and masterclasses when I was on Maynard’s band. Maynard did a lot of those; and by the time I joined the band, each member had a pretty good shtick they’d worked out to talk about. I learned a lot from that: just watching the way Maynard worked with kids was really interesting, and people loved it; so I tried to pick up little things along the way there.

I’ve always attended a lot of masterclasses, and I attend masterclasses for other instruments a lot. One of the best masterclasses I ever attended was by Ron Leonard, a cellist, giving a masterclass on Bach cello suites. You’ve already heard all the stuff that trombone players say about it; and when you hear an actual cellist describe that music, you go: “Oh my, duh….”

|

An ITF 2012 jam session with Wycliffe Gordon and Michael Dease. |

Improv

AI: I didn’t really start improvising until near the end of college. Because I started fairly late, certain things are fresher in my mind when I was in my 20s. So, when I encounter someone in their 20s starting out, I know exactly what they’re going through! I think that gives me a certain advantage in a way as a teacher. A lot of jazz musicians have gone through 30 steps but don’t remember the first 20 steps they took to get to that point. They’re now playing great and think, “Well, I just play.” And maybe they had always been up and running naturally. But I had to really work for everything that I did as an improvisor. I didn’t have that ear that some people have: when they can hear 16 bars of a Carl Fontana solo and write it out right away. I never had those kind of ears: I had to do everything a little more methodically and find my own way to learn how to do it.

Playing by Ear

AI: Most of my approach with improvising is trying to get younger players to delve into playing by ear: it is so important. Most players over 70 learned their instrument by playing by ear, the way people learn in a garage band. It is very raw and very pure. It’s the way Louis Armstrong learned how to play: you learn the songs, and you mess around with it in a non-written-out, non-theorized kind of experience.

That first little foray into improvising is very simple and innocent in a lot of ways. I think a lot of musicians’ first encounter with improvising is with a set of chord changes on a jazz band chart, and by then it is too late: you’ve missed out on all the stuff you really need to experience the right way. So I try to emphasize playing songs by ear a lot, especially in clinics—even if you’re not going to be a jazz musician. It is something that Ralph Sauer does really well. He would never call himself a jazz musician, but he has great ears. I remember when I subbed in the L.A. Philharmonic on Scheherazade, he had a practice mute in and was playing all the other parts—bassoon, clarinet—as they went by. This guy had transcribed the whole thing and was just playing along with them! Ear-play is really what is important. Even some good musicians neglect that; but it can really add a dimension and an authenticity to your playing when you really spontaneously hear what you’re going to do rather than plan it all the time. It gives you freedom.

For me as a classical trombonist, when I started doing more ear-play—playing songs by ear and transposing them into different keys—I think you’re getting past the trombone and trying to think of the instrument as just a voice for you. The more I did that—and it’s still ongoing—the more confidence I had and have when I play written music: I can hear in my head the notes before I play them. It’s kind of a no-brainer, but it’s something you can get distracted from if you’re thinking about: “OK, my embouchure’s here; my slide’s here; I put my right angle right there....” If you start thinking about all those details and then have to play “taaah,” you’re done; it’s over. On the other hand, you can just hear it and go for it—really what Arnold Jacobs was talking about with “Song and Wind”: you just get a good breath, have the music in your head, and then go for it. It can be a complicated process to get to that point; but when you finally get up and play, all that’s on your landscape is the note that you’re gonna’ play.

Attending a masterclass by Joe Alessi and Ralph Sauer at the Music Academy of the West. |

|

Finding His Voice

AI: When I went to the Joe Alessi seminar in 2001, it really changed everything I did, especially as far as my large-bore tenor-playing. I’ve not really talked about this that much. If there’s that moment where you kind of feel like you’re developing your own voice, that’s when it happened for me: in that year I found that I could express myself in classical music and not have my identity as a jazz trombonist be compromised. As an overall player, I felt like all my playing became a lot more solidified.

Joe gave me 10 or 15 things to work on; and over the course of the next 10 years, I just really worked on those things. And it’s ongoing. That was a really great experience for me. Some of the players there with me were some of the best and have all done really well. They were all younger: I’d just turned 40 when I attended. Those guys in their mid-20s were either right out of school or had just gotten their first gig or wanted to go up to the next level. They were hungry, practicing really hard, really enthusiastic, and super-positive. They treated me just the same way, and I really appreciated that.

I got my butt kicked in a really healthy way, and it was just what I needed: a little mid-life moment there, a great experience for me. I’m very grateful to Joe for the way he handled me, because I was kind of a different person for that seminar: older, with this weird commercial background. He didn’t treat me special at all, just addressed me with all my weaknesses: he’d jump right on them. I won the principal job with the Long Beach Symphony right after that.

|

The Long Beach Symphony low brass section: Alex Iles, Al Veeh, Phil Keen, and Doug Tornquist. |

Future Goals

MD: You’ve done a lot in terms of commissioning and premiering works for trombone; you’re doing so much for trombone-education. What are your goals and outlook for the next 20-30 years? 10 years? Tomorrow?

AI: Next 10 minutes? It’s tricky. I heard John Williams talk about this. He is a fascinating person, very smart. Someone asked him: “Do you have any advice for young composers?” And he said (I’m paraphrasing), “Well, first of all, I’m not really the person to give you advice because I’m much older than you. Your world is very different from the world I entered; you can’t even compare it. The other thing is that even if we were the same age, when I was in my 20s and 30s I couldn’t have told you what it is that I wanted to do. So I couldn’t really set the goal. And that was the best decision I ever made. If I had set what I’m doing right now as the goal, I don’t think I would have gotten there. There were no delineated criteria of things that I needed to do to get here. I found this path here. I couldn’t set out for it: it was purely just that each job was the most important thing to me. I gave each thing that I had in front of me all my attention. I didn’t think about where it was leading; I didn’t think, ‘I want to work for this director’; I didn’t think, ‘I want to make this much money’; I didn’t think about any of those things. All I did was do my best work every time I got an opportunity. That never changed: every time, that’s all I tried to do. I never tried to be innovative, although I do like experimenting.”

That was a great answer; I wish I could say it as succinctly as he did. It left an impression on me, and I realized that’s kind of what my dad had told me when I was younger. My mom and dad both said, “Keep your options open.” They encouraged me not to declare my major until the last minute in college. “Take all the classes you want: find out what you like, what you don’t like.” It’s important to find out the things you don’t like.

The Hollywood Bowl Orchestra trombone section and guest after a concert with the band Chicago: Bill Booth (principal), Craig Gosnell, Jim Pankow, Alex Iles. |

|

As far as for me in the future, I would love to continue playing. I know that everybody has a limited amount of time they can do studio work, for instance, because composers and contractors get younger and younger. They have their friends that they want to hire, and I’ve been very fortunate to be able to fit in with people both younger and older than me. I don’t see age as an issue: if somebody plays, they play. If somebody’s young, coming up, doesn’t have the experience, but can play, they’re OK for the job. It’d be nice to offer the job to somebody who’s experienced and is sitting at home, but there are opportunities to make music.

I’m not so concerned as to whether I’m doing studio work or live: I love playing and sharing music with people. It might not even involve playing: it might be more teaching. If I couldn’t play—if I got hit in the mouth or whatever—I could imagine doing other things in the music world that I could see being rewarding, working as an arts advocate of some sort. I love teaching, sharing, and turning people onto music if they haven’t been. You know that feeling when you get a young trombonist who’s just kind of into it, and you play them a record or show them something on the horn, and they just light up? It’s a great feeling, something a lot of people underestimate or forget about.

Green Advice

AI: I took some lessons with Bill Green, a great woodwind-player in Los Angeles. Why would I take lessons with a woodwind-player? He’d really helped a lead trumpet-player friend of mine, totally changed him; so I asked my friend, “What are you doing?” And he said, “I’m studying with Bill Green.” I asked, “What is he doing with you?” And he replied, “Take a lesson with him!”

So I did, and Green was fantastic. He made no apologies: “Play ‘Donna Lee.’” “What?” First thing out of the horn: “Play ‘Donna Lee.’ Maybe you should think about being able to play that right out of the case.” He also said, when I was just starting to work a bit: “There’s one thing I wanna’ tell you. You’re starting to work around town a bit; that’s great. But as long as you’re a professional, never forget what it was that drew you to that instrument. And every day, do something that puts you back in touch with it.” I thought, “That’s a good idea.” And 10, 15, 20 years later, every few years I think: “That’s so important.”

When I

look around at my colleagues—especially people who are struggling with whatever

it is in their life or their playing—very often the thing that gets them out of

it is that they maybe just decide to get a group together and just play

somewhere. Or put together a chamber group at their house. Whatever it is, do

something: forget about the money; forget about the professional part of it—just

make some music with some people. It’s so simple; it doesn’t have to be earth-shattering

or innovative or brand new and special. It just has to be what it was that

turned you on to music at first. And if you can somehow get a little bit of a

taste of that every day, it’s so healthy. That was one of the best pieces of

advice I ever got from a teacher. I found that has helped me so many times when

I’m starting to get that burnout.

|

With Andy Martin in Tom Kubis Big Band (Wayne Bergeron in back row). |

Favorite Story

MD: You’ve had such an incredible career, and I loved that amazing Mahler Symphony No. 3 story. Please share a couple more of your favorite stories that have happened to you in your career.

AI: Well, a couple of my favorites I probably can’t say! But Wayne Bergeron knows those really well. One tale involves Andy Martin. We were doing a Lalo Schifrin romantic action film called After the Sunset with Salma Hayek and Woody Harrelson; I think Harrelson was a bad guy. The scene had Woody in a place like Jamaica or the West Indies where there was a Jamaican-style band with pith helmets and white shorts. They’d actually recorded those musicians live during the scene; and it was kind of a rough-edged style compared to, say, the Eastman Wind Ensemble.

So actors were chasing Woody Harrelson through the band as he hid in the trumpet section, then in the trombone section; and for the aural perspective of the film, the goal of the score at that point was to sound as though you were there with him near the trumpets and then near the trombones. So at this one point where there’s two trombones playing right next to Harrelson, Andy and I were to record wild with the picture rolling. They had music for us, and we’re playing the part; but they say, “You know guys, it’s sounding a little too pristine, too correct: it’s right but doesn’t sound just right.” So we thought, why don’t we move back away from the mics and play louder? So we did that, but it still wasn’t quite right. “Why don’t you two come and listen to the playback? If you were up close to these trombonists on the film, you can imagine the sound would be pretty brash.”

With |

|

We try again; and they say, “It still sounds a little too coordinated.” So Andy and I looked at each other, and we flip our horns around and play left-handed. Now the music sounds a little rough! And they say, “It’s getting close!” So then I played off the side of my mouth, and Andy did sort of the same thing. Now we’re laughing; we can hardly play, we’re laughing so hard—and they say, “THAT’S IT!”

It was completely wrong technique; and I turned to Andy and said something like, “What would my teacher Roy Main say right now?”

MD: Well that’s the polar opposite of the Mahler 3 story but equally good.

AI: Sometimes you get paid to sound bad.

MD: Doing what the job requires: that’s the awesome thing.

Well Alex, it’s been great to spend some time with you tonight talking about your incredible career. I know I speak for the rest of the trombone world when I say that we look forward to seeing and hearing all the adventures of Alex Iles in the future, all the contributions that you’re going to be making. We’re all very grateful for your work and for your coming down tonight. So great to see you, as always.

AI: Thank you, it was a pleasure.

————————————-(begin sidebar)—————————————

(Also see the related transcription/analysis "Alex Iles’ solo on 'Sweet Georgia Brown'")

|

At the SliderAsia Music Festival. |

Instruments

Alex plays Schilke Greenhoe Trombones:

Large Tenor Trombone: Greenhoe GB-4, Laskey 59D mouthpiece

Small Tenor Trombone: Greenhoe GC-2, Schilke Custom “Alex Iles” mouthpiece

Bass Trombone: Greenhoe GC-5 dependent, Hauser Harwood mouthpiece

Medium Tenor Trombone: Bach 36, Bach 51C4 Mouthpiece

Alto Trombone: Kuhnl/Hoyer 122, Christian Lindberg 15cl mouthpiece

Contrabass Trombone: Kanstul, Bruno KB3 Spezial mouthpiece

Euphonium: Wessex “Dolce” compensating, Wick SM4 mouthpiece

Tuba: Wessex “Champion” Eb compensating, Wick 3L mouthpiece

Bass Trumpet: Wessex Bb BT-1

Web Site

Selected Discography

SOUNDTRACKS:

The Incredibles 2: Michael Giacchino

The Lion King (2019): Hans Zimmer

Spider Man: Far From Home:Michael Giacchino

Toy Story 4: Randy Newman

Star Wars: The Force Awakens: John Williams (track: Scherzo for X-Wings)

Up: Michael Giacchino ("Married Life" track)

Star Wars: Rogue One: John Williams

Coco: Michael Giacchino

Star Trek: Michael Giacchino

The Incredibles: Michael Giacchino

Despicable Me 3: Pharrell Williams

The Majestic: Mark Isham

AS A SIDEMAN:

Folk Songs for Jazzers: Frank Macchia

Everything's Gonna Be Great: Sal Lozano ("Bar B Que" track")

Intrada: Dave Slonaker Big Band

All the Bells and Whistles: Bob Florence Limited Edition

Stan Kenton 50th Celebration: Back to Balboa

The Phat Pack: Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band

XXL: Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band

Swingin' for the Fences: Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band

————————————-(end sidebar)—————————————

Trombonist/composer Michael Davis has enjoyed a diverse and acclaimed career over the past 40 years. He has toured and recorded extensively with the Rolling Stones, Frank Sinatra, and the Buddy Rich Band, has released 13 CDs as a solo artist, composed over 150 works, authored a dozen books for brass players of all levels, and appeared on over 500 CDs, television themes, and motion picture soundtracks. He is the founder and president of Hip-Bone Music. In 2011, the S.E. Shires Company released the Michael Davis signature model trombone and followed that in 2015 with the release of the Michael Davis+ trombone. Michael has performed and recorded with a variety of artists including James Taylor, Michael Jackson, Bob Dylan, Aerosmith, Tony Bennett, Jay-Z, Sarah Vaughan, Sting, Branford Marsalis, Peter Gabriel, Sheryl Crow, Bob Mintzer, and Paul Simon. He is active worldwide as a guest artist and clinician. Visit <www.hip-bonemusic.com>; e-mail <bonetown@mac.com>.

Ben Culver merited his B.M. Performance on trombone from Virginia Commonwealth University and his M.M. from Boston Conservatory at Berklee, also studying at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. While at VCU, he won the VCU Concerto Competition and was awarded both the Outstanding Achievement in Scholarship and the Award of Excellence in Music. His teachers include Norman Bolter, Gary Elwell, Antonio García, Davur Juul Magnussen, Ross Walter, and Harry Watters. He holds a Masters of Science in Computational Science from George Mason University and is now employed as a Data Engineer. Email him at <bjculvermusic@gmail.com>.