This article is copyright 1997 and originally was published in The Instrumentalist, Vol. 52, No. 4, November 1997. Some text variations may occur between the print version and that below. All international rights remain reserved; unauthorized duplication is prohibited. |

Count-Offs Set the Groove

by Antonio J. García

Many classically trained music educators discover their jobs include directing various-sized jazz ensembles—without ever having had the opportunity to lead such a group during their degree-training. And while their jazz-student peers may have logged many hours as a member of a jazz group, they, too, rarely get to “front” the ensembles. With the National Standards calling for greater improvisation skills and multicultural exposure, all music educators must increase their experience in many facets of jazz education. The material ahead focuses purely on one, critical element of jazz ensemble direction: counting off the music.

We have all observed ensembles that begin their music ambivalently, unsure, tepid...only to evolve into a secure rendition about eight measures later. There are reasons why this occurs—and corresponding solutions well worth seeking.

As within all art, technique is meant to serve as an expressive tool. If you’re already prompting excellent results starting your jazz groups’ performances, you may not need to read further—but I challenge you to do so in order to consider how you can and should pass such essential skills on to your own peers and students. Music educators can reach for an endless number of traditional conducting method texts for information, but jazz sources are painfully few. There is no substitute for observing successful jazz directors: the more we see, the more our approaches evolve—so read on!

The Length, Volume, & Content of a Count

A critical judgment of the ensemble’s current aptitude for accepting and internalizing the count-off is essential: the more experienced the musicians (individually and as a unit), the shorter the count-off required. One of my favorite jazz videos includes the image of Duke Ellington announcing the tune title into the camera, then simply pointing to his band—which launches perfectly into an intricate musical passage that defies reality! But had those wonderful musicians not been working together on the road for years, Duke’s gesture might have been disastrous.

I frequently observe ensemble directors counting off tempos of which they themselves are not yet sure, much less the surrounding musicians. Set the tempo in your head first—while quietly matching it to signature passages in the chart—then count it.

Too often the director knows the tempo but fails to provide the ensemble with sufficient notice of it. If you feel the group needs all the warning it can get, you can tap the tempo (often in half notes) on your chest while facing the group, giving nothing away to the audience. Then segue into the count. You’ll notice in the examples that follow I have provided a full count-off, plus bracketed the first half of many of them as optional. How much you use will depend on the experience and cohesiveness of the ensemble.

The volume of your count-off depends on two elements: function and theatre. Quiet tunes call for quiet counts, but louder works invite disagreements as to the dynamic of the count. Surely a festively loud count can add to the audience’s sensation of anticipation; but sometimes a crisper, quietly intense count may convey better to the ensemble the desired level of focus and intent. During recent work in Australia I was consistently struck with how inaudible the counts were—perhaps a reflection of the genteel manner of their citizenry. Their results, however, varied from conductor to conductor: some who were firm in their quiet delivery achieved results superior to many more “showy” counts heard in the U.S. So long as the musicians get what they need to start the music at their best, the choice is yours.

Tempo is the obvious ingredient of any count-off, yet we have all witnessed failures in that communication at times. The mood of the piece should be evident in the delivery so that the musicians prepare and breathe properly—yet we have heard too many count-offs that indicate tempo without offering any clue as to the music’s opening mood.

The third and most-ignored element of a successful count-off is the rhythmic style of the music. “One, two, three, four” won’t tell us much: is it swing or even-eighths? Is it going to be syncopated or primarily rooted in the ground beat? Is it bebop or funk? These questions and more can easily be answered within a two or four-bar count-off. Without those answers, less-experienced musicians are going to spend the first eight measures of the music searching for them, resulting in an less-than-inspired performance start.

The Hand & Voice as Baton

The classical instrumental conductor has the baton as tool for communicating the beat and its subdivisions. The jazz director’s voice provides this information, with the hand serving as a metronome. If the hand is uncommitted, no pulse is conveyed; if the voice is too slurred, no subdivisions are evident.

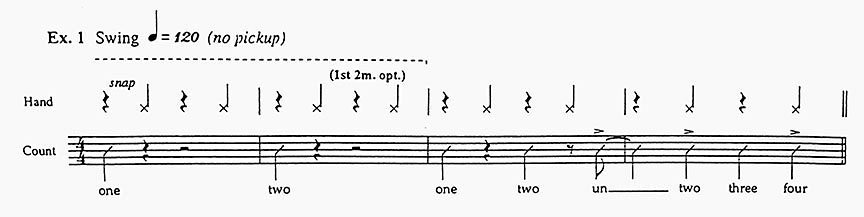

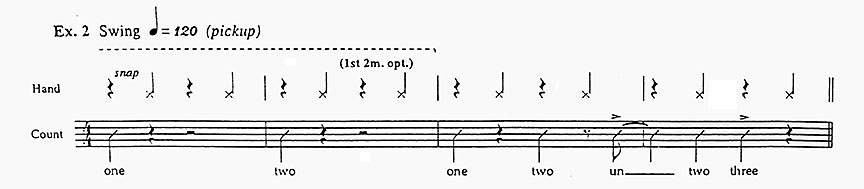

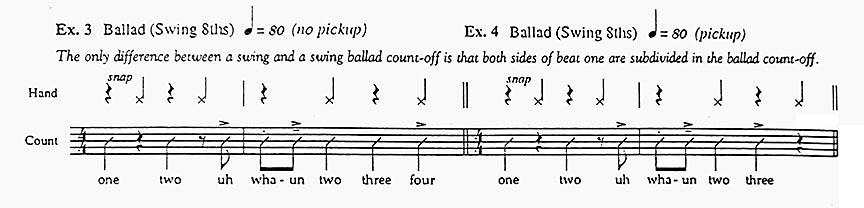

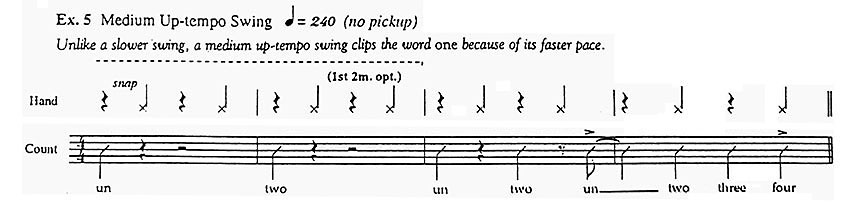

Too often I observe directors placing via their hands inappropriate emphases on quarter notes in count-offs. In order for the hand to communicate the groove, you must know where the ground beat is; and in jazz, that beat is usually not quarter notes—especially in swing, where the emphasis on beats two and four create a ground beat of half-notes crossing over the bar-line. Examples 1-6 show such a ground beat in the hand’s pulse.

[NOTE: For online study, I have now added mp3 files to these visual examples in order to demonstrate these concepts. To hear the audio, simply click on the Example. You may find it helpful to then drag the resulting playback window out of the visual way of the notated example so that you can see and hear at the same time. Some of these examples appear out of numbered order for ease of flow.]

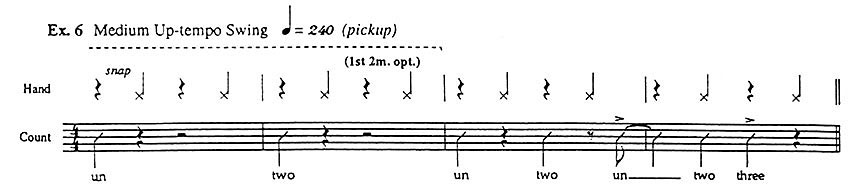

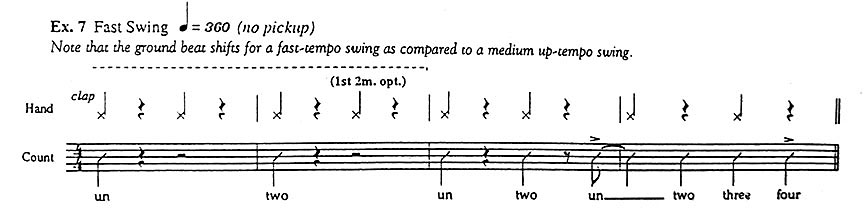

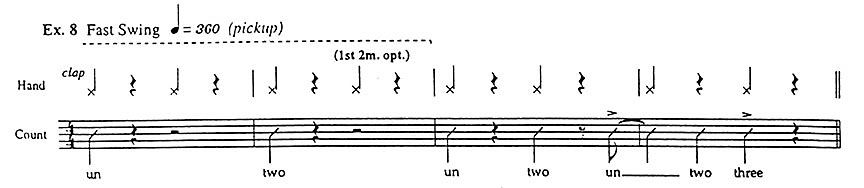

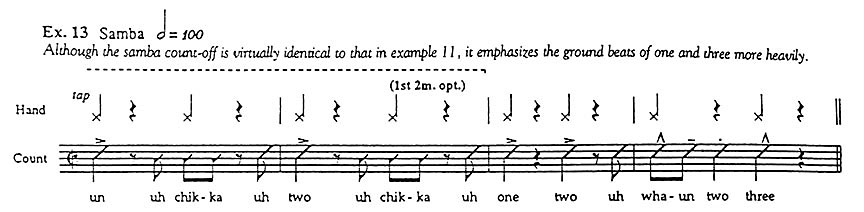

The faster a swing tempo, the greater tendency to move the ground beat back to beats one and three, as in Examples 7-8 and in the samba of Example 13.

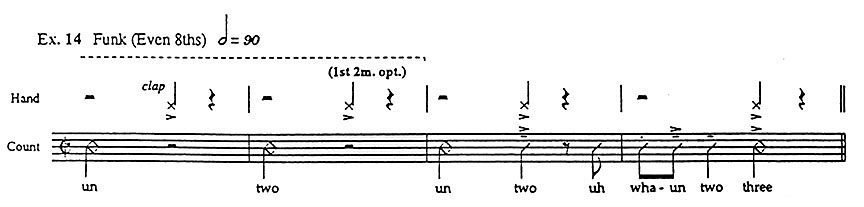

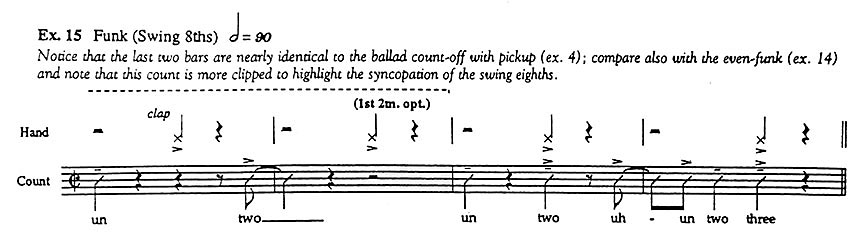

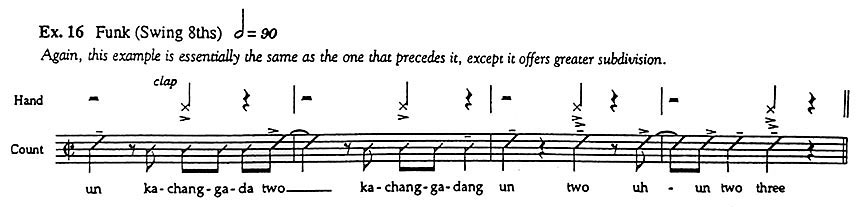

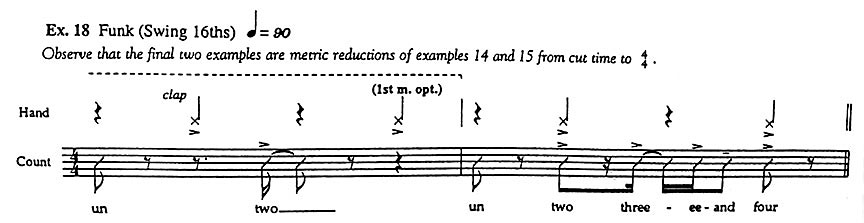

Cut-time funk grooves also often imply a ground beat of half notes on beats one and three, as in Examples 14-18, often with a greater emphasis on the second half of the bar (creating what is known as a “backbeat” feel).

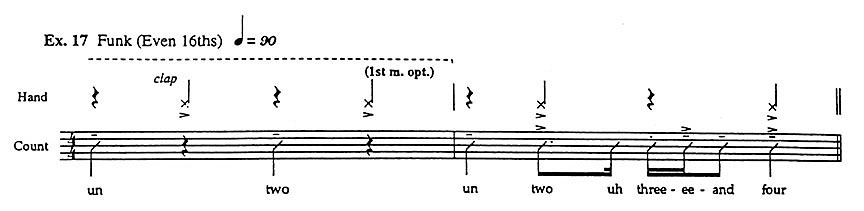

These also appear in metric reduction in 4/4 time (increasing the number of sixteenth-note passages), shrinking the ground beat back to the notation of beats two and four, as in Examples 17-18.

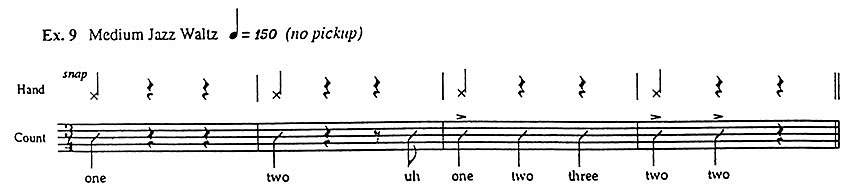

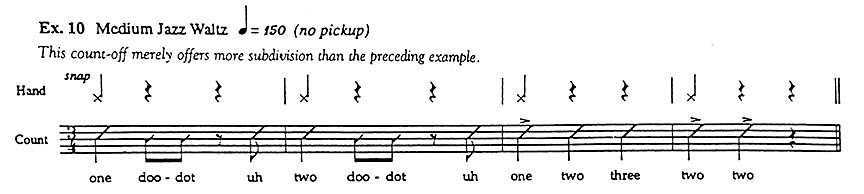

The triple-meter jazz waltz feel provides the greatest exception to all of the above, presenting a ground beat of dotted half-notes rooted on beat one, as in Examples 9-10 (though accents can also occur in the middle of the bar).

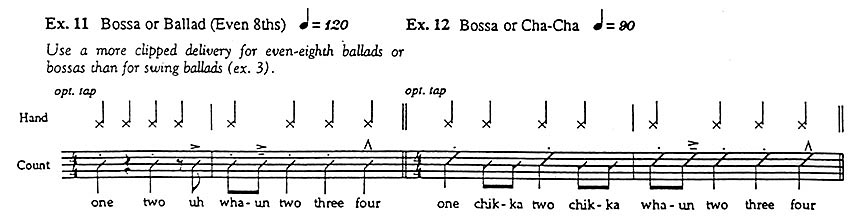

Thus the slower bossa nova (and related feels) in Examples 11-12 are the only samples which really invite a quarter pulse; and even then, the Brazilian bossa nova ground beat remains in the middle of the bar).

As you practice the examples, set your metronome on the appropriate ground beat—again, not usually quarter notes, with half-note clicks on beats two and four for all swing but the fastest tempos.

Many trends should be apparent in examining the sample count-offs. See how a syncopated note takes the accent that a nearby ground beat would have had. Two pairs of examples illustrate alternate means to the same end: Examples 9 and 10 and Examples 15 and 16, with the latter of each pair offering greater subdivision. Other similarities between the count-offs provided (beyond the preparation for pickup notes already discussed) include:

• Swing (Ex. 1) and Swing Ballad (Ex. 3): Ballad merely subdivides both sides of beat one of the last measure.

• Swing (Ex. 1) and Medium Up-tempo Swing (Ex. 5): The faster tempo clips the word “one” for greater impact.

• Medium Up-tempo Swing (Ex. 5) and Fast Swing (Ex. 7): Note the movement of the ground beat.

• Swing Ballad (Ex. 3) and Bossa or Even Ballad (Ex. 11): A more clipped delivery adds to the even-eighth nature of the count.

• Bossa or Even Ballad (Ex. 11) and Samba (Ex. 13): Virtually identical, with the latter emphasizing the ground beats of one and three more heavily.

• Swing Funk (Ex. 15) and Swing Ballad with Pickup (Ex. 4): The last two bars of the funk rhythms are nearly identical to the ballad count.

• Even Funk (Ex. 14) and Swing Funk (Ex. 15): The latter is more clipped in order to highlight syncopation that reveals the swing eighths.

• As indicated earlier, Exs. 17-18 are a metric reduction of Exs. 14-15 from cut time to 4/4 time.

The highly related nature of these counts also serves to emphasize how important swing feel is to an understanding of ballad and funk playing.

Since the hand is occupied with displaying the ground beat, the voice’s role in announcing the subdivisions of the groove is absolutely critical to getting the ensemble to internalize the opening measure before it performs it. If we were all leading Duke Ellington’s or Count Basie’s band, it would not be required—but less-experienced educational ensembles need the most accurate forecast possible of the music to come.

Here rages an old debate which will likely never die. Even this year I read in a conference clinician’s handout: “Don’t syncopate the count-off. ‘One, Two, Waaan, Two, Three, Four’ adds confusion right when you need it least.” I respectfully and forcefully disagree, as illustrated in the basic swing count-off I illustrate in Example 1’s third and fourth measure. In swing and related styles, a poorly syncopated count will indeed spoil the music—but the well-placed syncopation will instantly unify your ensemble’s vision of the groove. If your group begins its music sluggishly, highlighting the groove’s subdivisions can bring the music to immediate life.

Frequently one observes a director start the count well only to end unconvincingly, distracting the musicians at the most critical moment before they produce sound. Be clear throughout your count! Remember that even if the classical baton gives only one beat, it is a clear ictus to enable the ensemble’s opening attack. Similarly, notice that the last syllable of each of these count-off examples—no matter where it falls—is vocally accented. You’ll also find that observing rhythmic rests within these count-offs will accentuate the groove you are communicating to the ensemble: if you breathe and phrase in time, your musicians are much more likely to do so as well.

The Sound and the Look

Count-offs for each of the first four styles are shown as if the music begins on the following downbeat (Examples 1, 3, 5, 7)—succeeded by an illustration assuming a pickup to the music on beat four or the upbeat of four of the final count-off bar (Examples 2, 4, 6, 8). Pickups earlier in the measure would delete yet more of the end of the count. The remaining samples (Examples 9-18) do not forecast a pickup.

First get comfortable with making the appropriate ground-beat sound with your hand. Should you snap fingers, tap your palm, or clap your hands? While this is a highly personal choice, I have indicated my preference with each example: I tend to snap most swing (clapping as it gets faster), tap Latin grooves, and lightly clap funk beats.

Once you are comfortable delivering the groove with your hand(s), add your voice to the count-off examples. Again, technique should serve expression; so there is no need to obsess with syllable choices. Most of what’s printed here is simply the numbers one through four! But you’ll notice that the word “two” often appears on beats one or three: this is to set up an initially larger beat, allowing for divisions and subdivisions to follow.

The sounds below have proven most effective for many directors:

|

• “un” (Example 1 and later): Since “one” provides a gentle, rolling attack not always desirable, this offers a crisper, more percussive alternative for additional clarity in pronouncing the beat.

• “uh” (Example 3 and later): This is used as the syllable for pickup notes. While often interchangeable with “ah,” the darker “uh” provides greater emphasis on the downbeat syllable that follows.

• “wha-un” (Example 3 and later): A subdivided version of “one” emphasizes whether the groove is swing or even-eighth—and how accented or subtle that subdivision is to be treated in the music to follow.

• “doo-dot” (Example 10): By demonstrating the placement of the downbeat and upbeat of two in a jazz waltz, you announce the essential syncopation of the feel—much like a successful drum set pattern.

• “chik-ka” (Examples 12-13): Imitating a shaker or cabasa within a Latin groove count-off delivers the subdivisions with appropriate mood.

• “uh-un” (Examples 15-16): A subdivided version of “un” used when beat one is anticipated and accented.

• “ka-chang-ga-da” (Example 16) or variation: Imitating the drummer’s cymbals in a funk groove (the “ch” being the hi-hat) sets the tempo, mood, and style efficiently.

• “three-ee-and” (Examples 17-18): This subdivision of beat three may take some practice but will prove useful in sixteenth-based music—particularly funk.

Many of the most effective jazz directors are highly skilled at vocalizing the groove within their count-offs. If you need inspiration to voice percussion sounds, grab some Bobby McFerrin recordings! For additional information and exercises related to syllable choices and rhythm-section feels, please see my MENC Music Educators Journal articles “Pedagogical Scat” (September 1990) and “Fine-Tuning Your Ensemble’s Jazz Style” (February 1991).

Note the accents and other phrase markings included with each example, as they will greatly aid your quest for a natural, “jazz feel” delivery. Also note the visual emphases placed using two strata of vocal inflections in Examples 10, 12, 13, and 16: these suggest primary stress on points nearest the ground beats (“number” syllables), with a supporting sound for the subdivisions (“percussion” syllables).

Now that your hands and voice are delivering the tempo, mood, and style of the music, are you comfortable with what you see in the mirror? Do your hand and arm movements contribute to the visual imagery of the piece or detract from it?

Though there are many choices, a circular arm movement (elbow in, arm bent at 90 degrees) works well for most count-offs. Arrange your circle so that your finger snaps the ground beat at the outside of the circle (roughly where a conductor’s pattern might loop out for beat three). Avoid “hammering” movements downward that contradict the fluidity of most grooves you are addressing. Latin and funk beats that are tapped or clapped can be accomplished with your hands in (toward the center of your chest). How much of the count you wish to display to your audience is up to you.

Wielding & Yielding Attention

A classical conductor’s podium is rather small, but the jazz director is not confined to any one locale. If a jazz band’s music will start in the rhythm section only, I plant myself right in front of them to deliver the count. This serves not only to get their attention but to reinforce to all the other musicians on stage that they are not yet to sound! If the chart begins with a trumpet soli over rhythm section, I might be dead center in front of the band, my eyes and hands perhaps as raised as any classical conductor seeking the attention of the orchestra’s rear row. Otherwise, I tend to be a bit left of the center of the sax section. This allows me to be closer to the rhythm section during the count than most directors are, while retaining eye contact with the rest of the musicians.

If a director in rehearsal counts a tempo, the ensemble then delivers the music in an approximate, “generic” version of that tempo, and the director allows the group to continue, the message is clear: “Don’t take my tempos literally.” Avoid sending such a contradictory signal: stop the ensemble and ask the members if their tempo was faster or slower than your own. Most will know—but they may not have thought you cared about the difference.

When visiting a school’s jazz rehearsal, I might bring out my metronome and set it to a tempo, align my count to it, and start the ensemble—stopping the group after only four or eight bars. When I display the metronome’s sound again, the differential is often astonishing—after only eight measures or less of music! But just as astonishing is how quickly the students can focus upon and solve the problem. Once they understand that there are no generic tempos, they take pride in gaining control of the time. Such training in rehearsal will reap many rewards in later performance.

Again, jazz education is hotly divided on the issue of how much a jazz director should actually conduct. However, most successful directors will agree that they must follow through the count-off—as an athlete would follow-through any physical delivery in sports. Too often an inexperienced director will count-off and then cease all movement as the music begins, perhaps burying his or her head in the score. It is critical to keep your hands in the visual groove (not necessarily audible) for at least a few measures of medium-tempo time: make sure everyone’s got the message. If there is an immediate time problem dividing your ensemble at the chart’s start, the musicians are going to look up for speedy arbitration—and you want to be ready.

Once the music is firmly in your group’s hands, I recommend you withdraw from conducting as soon as possible. While many disagree, the bottom line is that most jazz groups (short of the rare seventy-piece orchestra) don’t have conductors: the musicians follow the drummer, lead trumpeter, or pianist. If there is a person literally conducting the ensemble in a professional situation, the visual activity is more for the audience’s stimulation than the musicians’. Basie, Ellington, Herman, and the like never conducted their bands as much as led them artistically: their conducting was effective in rehearsal—as much as it was required, as little as needed. From a career-training standpoint, therefore, students need to be able to perform without a conductor constantly spoon-feeding them the beat. Only then will they learn to listen across the ensemble for the kind of communication that is essential to any jazz group. Even if a professional jazz career is never their goal, they will have experienced and understood a jazz tradition that is essential to a complete music education.

That said, the time to wean your ensemble off of your conducting is in rehearsal, not initially in a performance! Allow your group the experience of “crashing and burning” in rehearsal—then ask them how it happened and how they can improve. They will never forget lessons learned from a dramatic failure. Use your freed senses to focus more fully on how the group is creating its music; you can grow to be even more effective in your advice for the ensemble.

You and the ensemble can then decide which tunes need ongoing conducting in performance and which don’t. You should be busy enough with any required cues, tempo changes, cut-offs, solo microphone adjustments, freewheeling soloists, and other mayhem—or just stand (or sit) aside and enjoy the music as they perform the chart independently in a manner that would make Count Basie proud. If you feel compelled to return to lead the big “shout” section that roars the music to its conclusion, enjoy knowing that they could have done it without you—that you are merely joining in the celebration of the music.

I’ve recently become more aware of how hungry the general public is to be a jazz conductor. Audiences love the sound—and look—of a great jazz ensemble. They crave the beat and fancy themselves up there on stage, counting off the group. When I had the opportunity to lead a hundred audience members in a jazz conducting workshop at Northwestern, I was struck by what a great time they were having, internalizing the beats and delivering the count-offs together. No wonder: you’re having a great time, aren’t you? So take advantage of the chance to get your public involved in a taste of jazz direction. You may find their enthusiasm a valuable resource for your program’s future.

D.S. al Coda

We share the knowledge that the best and irreplaceable way to learn about music is to listen. In the quest for the best jazz count-off, remind yourself to observe effective conductors and thus continually improve. I wish to acknowledge Professors Bill Dobbins and the late Ray Wright (of the Eastman School of Music) and Professors Joseph Hebert and John Mahoney (of Loyola University of the South) for their profound and positive influence—as well as the countless other musicians who have imprinted their conducting style on my own.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic, chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh, Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. He has fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program, with hundreds of thousands of dollars already in hand.

A Bach/Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist, bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins: Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer, he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Mr. García is a Research Faculty member at The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Durban, South Africa) and the Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal. He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His book Cutting the Changes: Jazz Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he served as Editor of the Jazz Education Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997 Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson, “The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes: “Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s “splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing” and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and “first-class writing of special interest.” The Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely” composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

The Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute, Mr. García has adjudicated festivals and presented clinics in Canada, Europe, Australia, The Middle East, and South Africa, including creativity workshops for Motorola, Inc.’s international management executives. The partnership he created between VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz Improv; Music, Inc.; The International Musician; The Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards. Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of 434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Arts’ 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service and in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame. Visit his web site at <www.garciamusic.com>.

| Top |

If you entered this page via a search

engine and would like to visit more of this site,

For further information on the resources referenced above, see