Chick Corea's Concerto for Trombone: A Stroll

by Antonio J. García

ITAJ Associate Jazz Editor

|

Joseph Alessi, photo credits: |

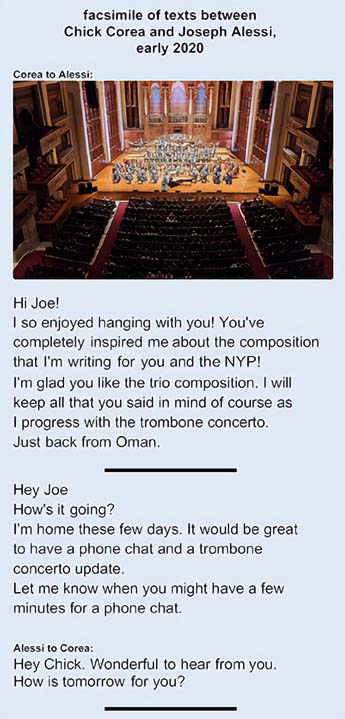

For a “stroll,” the path of this trombone concerto was quite a journey: a guest jazz pianist invites the New York Philharmonic’s trombonist to a jazz club; the trombonist is inspired to contact a jazz composer, who invites him to visit; a consortium of orchestras co-funds a commission, completed before the composer’s unexpected passing; the soloist learns new digital software to rehearse; COVID alters the premiere date, locale, and audience; the trombonist finds a new bell before boarding the plane to Brazil; and a new, strikingly original musical work is birthed in a performance livestreamed around the world. All in all, the path might be more representative of a tango than a stroll!

Joseph Alessi needs no introduction to most ITAJ readers. Appointed Principal Trombone of the New York Philharmonic in the spring of 1985, following years with The Philadelphia Orchestra and L’Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal, he has also performed as guest principal trombonist with the London Symphony Orchestra in Carnegie Hall led by Pierre Boulez and is an active soloist, recitalist, and chamber music performer. Among solos he has performed with the NYP is Christopher Rouse’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Trombone Concerto with the Philharmonic,” which had commissioned the work for its 150th anniversary celebration. His recording of George Crumb’s “Starchild” on the Bridge record label won a Grammy Award. In addition to solo engagements around the world, he has recorded and performed extensively with The New York Trombone Quartet, Four of a Kind Trombone Quartet, World Trombone Quartet, and Slide Monsters Trombone Quartet. He has also performed with the Maria Schneider Orchestra, the Village Vanguard Orchestra, and has recorded with jazz greats J.J. Johnson and Steve Turre. In 2002 Mr. Alessi was awarded an International Trombone Association Award for his contributions to the world of trombone music and trombone playing, and in 2014 he was elected President of the ITA. He is on the faculty of The Juilliard School and is a clinician for the Eastman-Shires Instrument Company; he plays exclusively on a Shires-Alessi model trombone.

To say that Chick Corea (who passed away February 9, 2021) was a jazz musician is a severe oversimplification. His childhood piano teacher, Salvatore Sullo, had studied with Alfred Cortot—thus a direct pedagogical lineage to Frédéric Chopin. Nearly forty years ago Corea had written his “Septet for Winds, Strings and Piano” for the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center; and other cross-genre works followed, along with performing with orchestras such as the London Philharmonic and Seattle and Oregon Symphonies. Nonetheless, jazz was his primary home, recognized as a National Endowment For The Arts Jazz Master, a Down Beat magazine Hall of Fame recipient, a 25-time Grammy winner, the fourth-most-nominated artist in the history of the Grammys, and three Latin Grammy Awards (the most of any artist in the Best Instrumental Album category). From straight-ahead jazz to avant-garde, bebop to fusion, children’s songs to chamber music, along with his far-reaching forays into symphonic works, Chick touched an astonishing number of musical bases in his illustrious career. His new trombone concerto is a co-commission by the New York Philharmonic, São Paulo Symphony Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic, and Fundação Gulbenkian (Lisbon).

John Dickson is a French hornist/pianist composing music for film, television, and the recording industry as well as performing with such artists as Barbra Streisand, Elton John, Seth MacFarlane, Ray Charles, Alanis Morissette, Chick Corea, The Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, Shirley Horn, Warrant, Harry Connick, Lionel Ritchie, Usher, and “Weird Al” Yankovic. He’s also performed on over 300 feature films, TV shows, trailers, and national commercials. John has composed and arranged music for nearly every facet of the entertainment industry including for the hit USA series “Burn Notice” (for which he received four ASCAP “Top Television Series” awards), the blockbuster film “XXX,” many cable and network TV shows and movies, and of course chamber and orchestral music with Chick Corea. Their collaboration “Spain for Sextet and Orchestra” won the Grammy Award for the Best Instrumental Arrangement in 2000.

I spoke with Joseph Alessi on March 13, 2020 and with Chick Corea on November 10, 2020, prior to the August 5, 2021 concerto premiere, then spoke again to Alessi on September 10, 2021. Though they did not hear each other’s remarks, I have constructed the interview below out of those conversations with me, along with a livestreamed ITA interview of Alessi and Dickson on September 26, 2021 by Kevin McManus for an ITA Artist Zoom Session, plus Alessi’s Facebook post of his program notes following the August 2021 premiere.

Even as we mourn the passing of Chick Corea, we celebrate the exciting debut as well as future performances of Corea’s final large-scale composition, “Concerto for Trombone: A Stroll.”

—Antonio García

|

Joseph Alessi premieres Chick Corea’s Concerto for Trombone: A Stroll with the Orquestra Sinfônica do Estado de São Paulo (OSEP), Giancarlo Guerrero, conductor, August 5, 2021. photo credit: |

THOUGHTS FROM JOSEPH ALESSI (March 13, 2020)

An Idea

Antonio García: How did the idea for this concerto arise?

Joseph Alessi: Several years ago the brilliant Japanese pianist Makoto Ozone was performing as a soloist on Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue with the New York Philharmonic, and we became friends. I was long a fan of his recordings with vibraphonist Gary Burton. NY Phil music director at that time, Alan Gilbert, mentioned to Ozone that I play a little jazz; so Makoto invited me and a few others to play some blues with him as an encore at his NYP concerts; and he also invited me over to Japan to play in his big band there, “No Name Horses.”

A few years later he returned to New York City to perform within Burton’s farewell concerts; and he invited Maestro Gilbert and me to Birdland, where Makoto was performing with Burton. During the second set, they played a beautiful tune composed by Chick Corea called “Brasilia.” When I heard this wonderful piece, I felt so inspired that I approached Makoto and asked him if he thought that Chick would ever consider writing me a trombone concerto.

Makoto texted Chick, who a few days later replied that he might be interested. I sent Chick my information, and we spent several months texting one another about a possible concerto. While at first Chick was hesitant about working with a symphony orchestra, I assured him that the New York Philharmonic was well-versed playing any style of music and that the professionalism of the orchestra was unmatched in regard to rehearsing and performing new music. Chick eventually agreed to write the trombone concerto—a very happy day for me!

He came up to New York to play at a club and invited me to sit in. Our NYP music director, Jaap van Zweden, also came. I played “In a Sentimental Mood” with Chick and his band, and that went well; and after that, it was full speed ahead with the commission.

AG: What sort of interactions beyond texting did you have during the compositional process?

JA: Chick then invited me to visit at his home in Clearwater, Florida, where we played together, including on “Brasilia.” I had the guts to improvise with him, and he wasn’t judgmental: he wanted to see if it would be possible to include an element of improvisation in the concerto.

As we discussed ideas about the piece, I had to pinch myself. I couldn’t believe I was talking across the table with him; it was surreal. He showed me some other pieces he was working on. One was a jazz trio piece; and I said, “If you want to include anything like this within the concerto, please go right ahead. Whatever you want to write, I’ll figure out how to play it.”

|

AG: Chick has such a legacy of writing magnificent music, some of which is also technically astounding yet always in service to musical expression—sometimes to the point where it sounds far easier to perform than it actually is. His music spans some pieces that a non-pianist could play, then of course music that almost no one else could perform. So that offer of yours was a brave statement, but a great one!

JA: Right. And you get what you wish for! I might live down those words, but I really wanted him to explore the instrument’s potential. I visited again a couple of months later, when he showed me some of the progress he’d made on the piece. I played several sections of it along with him, and he was pleased at how the music was going; so then he sent me the first six minutes of the concerto, which is what I had by March 2020: a very convincing MIDI demo along with a PDF of the trombone part.

He had been touring constantly; but with the arrival of COVID in the world, performances shut down; so he had more time to write after March—a good thing for the commission, but a bad thing for his own performance schedule.

Chick is a gentleman, totally down to earth; and as great a musician as he is, he’s the most humble man in the whole world. And he truly respects classical musicians; he loves Stravinsky and Mozart in particular. We hit it off in part because of our mutual love of Stravinsky’s ballet Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss), which I’d performed with the San Francisco Ballet many years ago. So I’d started playing all the trombone solos from that piece for him, and we shared our appreciation of that music.

AG: How did you fund the creation of this music?

JA: A consortium of orchestras are backing this work. Along with the New York Philharmonic, we have the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic, and Fundação Gulbenkian (Lisbon). And at the NY Phil we hope that he will perform a Mozart piano concerto on the first half of the concerts, plus participate in some Young People’s Concerts(TM), capitalizing on his presence during that time.

AG: How is the concerto organized?

|

Alessi sits in with Corea at |

JA: Chick and I had talked about starting the piece with just trombone alone, which is exactly what happens. The composition begins with a substantial introduction titled “A Stroll Opening.” It includes a free improvisation by the solo trombone, followed by a dialogue with harp, percussion, and piano. The second movement, “A Stroll,” was inspired from his time living in New York City, walking uptown and downtown while taking in the sights and sounds of the Big Apple. In “Waltse for Joe,” the third movement, Chick was very keen on exploring the very lyrical side of the trombone; so this part was composed to do just that. I would describe this waltse as being reminiscent of the music of Eric Satie. “Hysteria,” the fourth movement, was composed at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Chick said he chose this title to exemplify the chaos going on in the world at that time.

The fifth and final movement, “Joe’s Tango,” ends not being what Chick originally composed. The first version of this movement had ended peacefully, similar to the previous movements; but I had been hoping for a larger and more dramatic ending. I had to summon a lot of courage to contact him to ask if he might consider rewriting the ending. When Chick asked me why, I explained to him that his music suggested to me the idea of two strangers, one reluctant to really engage, dancing with one another in an increasingly impassioned tango, finally surrendering and triumphant in love for one another.

The first several movements are technically not incredibly challenging; so I believe a lot of trombonists with various levels of experience will want to perform them. And there are various places in the score where it would be possible to open things up for more extended improvisations.

AG: The flexibility of this concerto will be a big plus for the trombone-world and for the jazz/classical-intersecting world.

JA: I believe he conceives of the concerto as a modular piece: you could perform a movement on its own, or the movements in a different order.

AG: And I hope that he or someone he authorizes will create a piano reduction so that the piece becomes more accessible to trombonists without the availability of large ensembles. That would assist its becoming a staple at universities and at other public performances of the trombone.

JA: There’s also interest in creating a wind-band version of the piece.

AG: My congratulations to you on moving this project forward into reality!

THOUGHTS FROM CHICK COREA (November 10, 2020)

Note: When I spoke with Chick Corea, he was energetic, upbeat, creative, interactive, articulate, humorous,—in short, everything you’d expect him to be. There was no indication to me that he was ill or even aware he was ill, and perhaps at this date he had actually been unaware.

The Construct

Antonio García: This is a great opportunity for me to catch up on your inspiration for the piece and where it stands. I understand that you’ve actually covered quite a bit of ground with it already.

Chick Corea: Well, it’s done! The concerto is complete, just waiting to be aired with Joe and the orchestra. The problem is that the New York Phil is renovating its hall this year; so the premiere can’t be there. Joe probably told you he’s thinking of premiering it at São Paulo.

But it was a labor of love and a great new challenge for me to write for Joe and the great orchestra. I love writing: that’s my very biggest passion. The piano-player in me is only a servant to the composer. So when I get an opportunity to write for a player like Joe, backed up by an amazing thoroughbred-racing organization like the New York Philharmonic, it was a thrill. I can’t wait to hear how it goes down.

AG: He mentioned that you had an inspiration to write it perhaps as if a stroll through the neighborhoods of New York in some way.

CC: I started to get to know Joe: he came down to Florida; and we hung out and talked about the piece. He and I have a lot in common in terms of tastes and family background.

I was just filled with New York City because New York City is my home, although I wasn’t born there. I was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts; but I guess I was 17 when I graduated high school and moved directly to New York. I really cut my teeth there, and I lived there through the ‘60s and the ‘70s. And it’s just my place, you know: I love it.

So when I was talking to Joe, all that New York-feeling came back to me. I hadn’t thought of any music yet; but once I started writing, I saw that I would like to cover a lot of different rhythmic and emotional ground. And at that moment, right when I was writing that first movement, I thought of something that I’ve never really done—which maybe next lifetime I’ll get around to—which is to start walking from way uptown in the Bronx and connect with Broadway, and just stroll all the way down Broadway to as far south as I can go. I could envision that because I’ve been in those areas so much. It’s like walking through the world. It’s like moving through the universe of human beings and activities and cultures and commerce and art and private living and interesting people on the street and the whole of it.

So that became my image. It was a stroll; and that’s the name of the first movement: a stroll on Broadway from top to bottom or something like that. I wrote a tune for my first album back in ‘65 called “Straight Up And Down,” and it was a similar image of the avenues of New York going straight up and down.

AG: As they do there. I’m originally from New Orleans, 25 years born and raised; and nothing goes straight up and down there. The streets are all curved with the river. So I have no sense of direction whatsoever. I think part of that’s genetic, but part of it was I never knew “east/west”; no streets were numbered in sequence. So when I first went to New York, it was such a shock to experience something laid out on a grid. What a concept!

CC: Yeah, they did that with a lot of forethought back in the day.

The Instrument

AG: You’ve certainly featured trombonists in your groups at various times, most recently perhaps Steve Davis. Did writing this concerto for the trombone offer newer possibilities or concerns that you had not anticipated? Of course, Alessi could probably play about anything; but nonetheless, did the instrument draw you in some direction?

CC: To be blunt and honest, the instrument had nothing to do with it at first. My inspiration was Joe, when I met him, and his genuine passion to want me to write something. And then of course I quickly learned of his prowess by my going through YouTube recordings and the recordings he sent me: just like you said, this guy can play anything!

Through my life of composing I’ve learned that that the best musicians I’ve worked with love a challenge. So when I’m writing for an instrumentalist with the capabilities and artistry of Joe, I don’t try to study the instrument; I don’t try to figure out: “Can it do this...or that?”

I think that the most we’d discussed was when I wrote this one phrase. I said, “Hey, Joe: you know I’m hanging on that high D up there. It sounds pretty high on my plug-in trombone here. What do you think?” And he said, “No problem.” And that was our technical discussion. I have learned that a great instrumental virtuoso will accept the challenge of a written piece of music if they like the music. They will adapt the written notes to make it come out of their instrument the way they conceived it should come out. That’s the genius and beauty of an artist at that level. So I don’t even worry about range. If the phrase goes too high or too low, that genius will find an answer to that.

What I always do if I’m writing for specific musicians is tell them: “When you see my score, if something doesn’t feel right to you, just change it. Drop the note out, or add your own note; or call me up, and I’ll fix it.” But that hardly ever happens.

AG: The artists make it work on the instrument: they find that voice.

CC: Yeah. And then as I write, I get to know the instrument pretty well—both through writing and through performing with Steve Davis, who is an amazing instrumentalist; so I’ve gotten to see what the ins and outs of the instrument are, how it sounds in various combinations.

You know, in my band Origin, besides Steve Davis on trombone, Steve Wilson was playing soprano and alto sax and various flutes. And I had Tim Garland at one point playing tenor saxophone and bass clarinet and another flute. So we had all different combinations of timbres going with the trombone.

AG: I’m glad you mentioned Steve Wilson: we’re proud to say he’s one of our alumni from Virginia Commonwealth University, though he left us some years before I arrived here in 2001. We’re very proud of him and all the work that he’s done with you, with others, and on his own.

CC: Yeah, Steve is amazing.

AG: And a great human being as well.

CC: Yes, absolutely.

Alessi and Corea at The Blue Note |

|

Adaptations

AG: So for those of us trombonists who don’t have an orchestra or concert band handy, often what happens in the educational world is that a piano reduction is created of the ensemble parts so that at some point after the premiere, the piece can also be played by trombonists in colleges and universities who may not have the full ensemble—or that level of ensemble—available. Might you consider creating a piano reduction for the piece?

CC: Well, I’m glad you reminded me. I’ve turned all my orchestration-notes over to my orchestrator, John Dickson. He’s a French hornist, pianist, and composer, a very adept musician who lays it out for me on Sibelius.

A lot of my sketch-writing for the concerto was written on piano staves, which I then expanded for the orchestra. So there was this original piano sketch, but it wasn’t a reduction.

AG: It was the essence.

CC: Some of the essence. But as I got used to using Logic and all my plug-ins to make a real demo as I went along, then there were big, long sections where I didn’t use a piano-sketch at all: I just went directly to the Logic instruments and started writing like an orchestra composer with trumpets, trombones, and so forth. So the piano-sketch is sketchy.

But mentioned to John, my orchestrator, that I really wanted to make a piano reduction. And he said he could, and he’s a really good pianist. So I’m glad you reminded me that because as soon as I finished the project, and Joe liked it, and it went to the orchestrator, and we finished it all up, with the engraver putting it in a layout that fulfilled the contract of the New York Philharmonic, then, you know, I thought: “Okay, wow, that was nice; and Joe likes it”; and I moved on. But I had I had forgotten about the piano reduction, and I’m going to make sure that happens.

AG: It would be a great boon for the college, university, and pro markets, you know. The professors would get a lot of traction with it, as well as some of their students; they will have already performed it with the piano reduction and fallen in love with the piece. Then in the future some of those individuals may get to perform with an orchestra and are thus ready to choose it when the opportunity arises. And while it benefits the composer, it really suits the whole idiom of trombone because a lot of the music that is published for orchestra is out of reach simply because of the instrumentation.

CC: It’s the same for solo piano concertos. That’s how I practiced my Mozart and my Gershwin: by piano reductions.

Forming a Plan

AG: I understand that when you do unite with the New York Phil, perhaps in the first half you might be playing some Mozart. Is that the game plan?

CC: It’s all up in the air right now. I hope I get to play with them, but we will see. At this moment I’m really looking forward to the New York premiere with Joe.

AG: Wonderful. Well, I’m very grateful for your time. Is there anything else you wanted to share before we call it an evening?

CC: Oh, it’s up to you, man. It’s a deep well, this subject of composing and the trombone concerto. It already has a life of its own: there’s a MIDI demo that I gave to Joe that sounds good, with all the parts and initially me playing Joe’s trombone part. It doesn’t have as much expression, but it lives: there’s a lot of depth in there. I hope that after Joe gets it going, other trombone players will like it enough to play it.

AG: I’m sure they will. And let’s say Alessi premieres the work in Brazil. Maybe a year from now I do a follow-up interview with you both together to run in advance of or right after the New York performance. But I’m very grateful for your time; thank you so much.

CC: Tony, thank you. It’s a pleasure meeting you, and my best to everybody in your area there. Onward!

AG: Thanks for everything you’ve given music and music education over the years.

CC: Thanks, Tony.

|

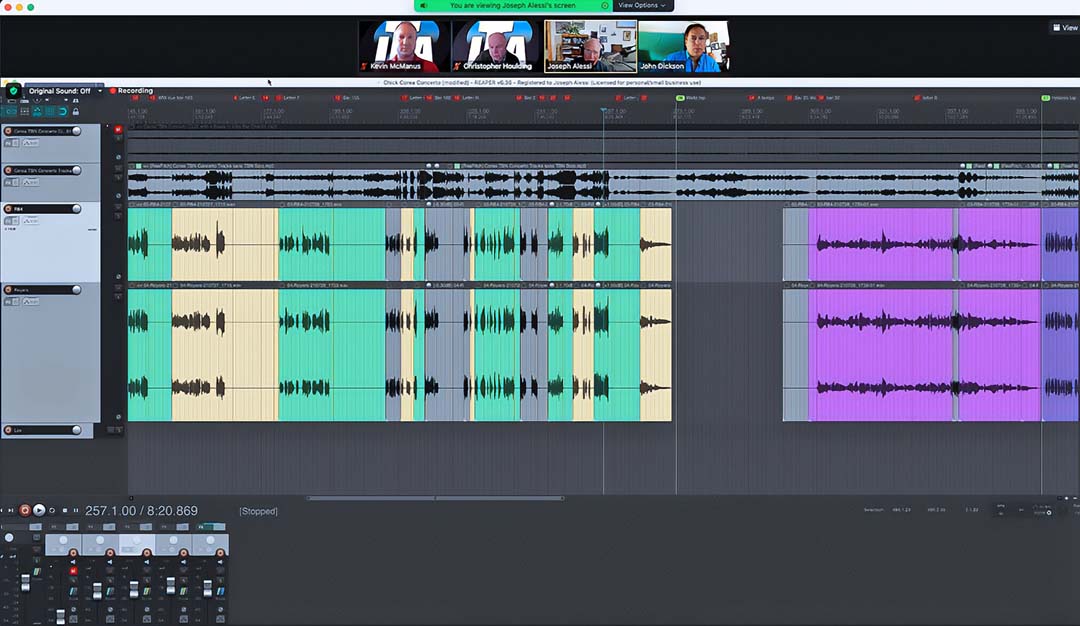

| At the September 26, 2021 ITA Artist Zoom Session, Alessi shares with participants his screen and sound of the DAW Reaper playing back the concerto MIDI mock-up utilized for his own practice. Shown at the top are moderators Kevin McManus and Christopher Houlding along with Alessi and orchestrator John Dickson. photo credit: ITA screenshot courtesy Antonio J. García |

THOUGHTS FROM JOHN DICKSON & JOSEPH ALESSI (September 26, 2021)

John Dickson: I’d known Chick since 1994, when we were recording the songs of West Side Story as reimagined for pop and jazz artists of the day. He and I had the idea of rescoring the “Rumble” piece for his first Elektric Band on one “side” and some rock-and-roll heavies on the other “side.” So we got to know each other through that process and developed a nice rapport; he had been one of my heroes since I’d been a kid. I got to score his “Spain” for jazz quintet and orchestra, which we premiered live in Japan; then I reorchestrated it for his sextet and orchestra, which we recorded in 1999 with the London Philharmonic. And I’m actually sitting on scores for some pieces that Chick wrote during that period for large ensembles that have never been performed.

Because more recently he lived in Florida and I in Los Angeles, I was very pleased to receive a voicemail message from him in mid-2019, inviting me to work with him on the trombone concerto. He’d been listening to a lot of Stravinsky, including The Fairy’s Kiss; and he told me that he wanted to keep this concerto “light on its feet,” with a chamber feel even though he was writing for a symphony orchestra with a full complement of strings. So we came up with a triple-winds, standard-brass score that allowed us to have doublers—but sometimes only five people on stage are playing with the soloist.

At this point he was moving from paper to Logic, demoing certain passages in Logic; things were progressing gradually. But I think this would have been a very different piece if we had not entered COVID-lockdown: when his tour abruptly ended in Europe, he called me and said, “Let’s move this forward.” Even though there wasn’t a looming deadline, he wanted to complete it in light of other projects he foresaw ahead as well that he could write during lockdown. And he would not have written the “Hysteria” movement had it not been inspired by the COVID era!

So he provided me with his sketches and Logic demos and invited me to “start painting” the fuller orchestration according to his guides. During the orchestration process, Chick and I were texting constantly and e-mailing files. I have a folder with 40 revisions of this piece as he thought of new ideas. And because of the digital nature of the Sibelius notation-software I was using, along with the sound-library Note Performer, I could write ten pages of music and then send it to him as a demo; so he could hear it instantly as well as see it.

Joseph Alessi: When Chick first sent me the trombone part, there was no orchestration demo. And the part was all in treble clef—even the lowest notes! So I learned treble clef to a depth I’d never done before, counting the lines and spaces. But despite the many unusual intervals within the solo part, I got to the point where at the end of the day I could sing a given section of the piece—and that’s when you really know it. The next time I perform this concerto, I may well do so from memory. I would like to try that.

I believe every trombonist out there should be able to play in a lot of different styles, and pretty easily so. It’s all music. Getting to meet J.J. Johnson and hearing him play, along with my high school experiences, was impactful. You have to be versatile. I wish I would have gotten started earlier in my harmonic knowledge for improvisation, but I plan to continue to grow in that area.

One of the things I do with new music, believe it or not, is write in the slide-positions of tricky areas, especially the alternate positions. I do that very early in the process so that every time I practice the piece, those decisions are set and the same: I’ve made all the difficult decisions already.

JD: Eventually we could send Joe a reasonably good audio mock-up of the whole piece as a valuable practice tool, and he could practice at tempo or instead at a slower speed.

JA: And recording my practicing with it at a slower speed—an approach I always tell my students to do—really reveals any concerns about slide-technique or attacks that I need to remedy. But I certainly didn’t know how to do any of this digital manipulation at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. The first day I heard John’s orchestration via the MIDI demo, I thought, “Oh, my God, this concerto is great!” I had already had that feeling from practicing the trombone part alone because the part is fun to play, but hearing the orchestral mock-up really brought it in focus. So I started using digital audio production software called Reaper: it’s free. I bought some mics and started practicing the piece along with the audio mock-ups.

Though I’d benefited so much from practicing the piece along with the MIDI demos, everything did change for me when I first rehearsed with a live orchestra. I could then really hear the intensities of the orchestra and determine which of my notes I really needed to lean on. And since the opening of the piece is free-form, I had to be fully aware of what was going on in the score for harp, piano, and percussion: we had to have our own ten-minute rehearsal to focus just on that. But overall, since I knew the piece so well from my MIDI rehearsals and score-study, I wasn’t at all nervous when I took the stage for the first orchestral rehearsal. I now feel that this is the best way to learn a new piece of music premiering: hearing and rehearsing with MIDI audio demos.

And I’ve always loved playing a horn with an 8-inch bell; it’s as close as I can come to a small-bore horn without switching mouthpieces. Just two days before I left for Brazil, Shires sent me an 8-inch bell that I loved and that lends itself very well to this piece. And I may use this smaller bell for other solo pieces in the future.

JD: When I heard the premiere via livestream, I was so thrilled to hear it performed by a live orchestra—and triumphant under such circumstances! As is typical, the ensemble has so little rehearsal time; then the woodwinds and brass are separated by many feet and even isolation booths; and yet the performance was brilliant. Five years from now, a lot of musicians will have heard this piece and will know what to expect when addressing it; but this orchestra dealt with it cold.

Regarding the ending of the concerto: when I received Chick’s score, I had thought the last pages were simply where he had currently stopped writing. But Chick said, “No, that’s the end of the piece.” And he had his reasons why he’d wanted the piece to fade away at the end. But I said to him, “I’m a French horn player; and as a brass player, I would want an exciting end to the piece, burning the house down.” And he said, “We’ll see; I’ll talk to Joe and see what he thinks about it.”

Then, after he spoke with Joe, he called me back and said, “Well, I guess it’s going to be a big ending! Joe had a really good reason for it; it made a lot of sense.” And it is a wonderful Coda: it hangs by itself. I was pleased to see in the livestream from Brazil that Joe picked the Coda as his encore; it makes perfect sense—if you want to roll through those high F#’s again!

A few months ago, prior to the premiere, Joe and I were Zoom-meeting together; and Joe played a little bit of the piece along with the MIDI demo I’d sent him. It was the first time I’d heard his live trombone with any form of the concerto, and I just wish that Chick had still been with us: he never got to hear Joe play it but would have been so knocked out by Joe’s performance and interpretation of the work. This concerto represented a whole new direction for Chick, who was hoping to do more work prompted by this piece.

JA: I never thought in a million years that I would get to know Chick Corea as a friend, to eat together, to laugh together: it was a privilege. And then I thought he would be around for a long time thereafter: it was very shocking to lose him when we did.

JD: I may be one of the luckiest musicians alive, getting so much time to play music in Chick’s house, sharing the same piano bench, able to hear his thought-process without the burden of performance. And I have to be grateful to Chick for bringing me in to work on a piece for one of my heroes, Joe Alessi, whom I might otherwise never have met. Chick was so inspired to write for Joe and didn’t take any of my advice about reining back a bit: he wanted to hear you perform it. And it’s phenomenal to hear it realized by you and the São Paulo orchestra; I’m very grateful. The next step Chick and I were going to work on was the piano reduction—and then perhaps later the wind-band adaptation.

CHICK COREA: IN MEMORIAM

Joseph Alessi (posted August 2021 on his Facebook page): In November of 2020 I heard briefly from Chick, who said that he was not feeling well and would be out of touch for a while during treatments. It was devastating for me to learn on February 9, 2021 that he had died. We had expected that he would be with us in Brazil to hear and enjoy this music, as well as playing the piano part of this concerto onstage.

He is sorely missed, and I wish I had been able to say goodbye and tell him how wonderful it was to collaborate with him. I dedicate my performances of his concerto to the life and memory of Chick Corea, a musician of true genius and one of the kindest and most sincere people I have ever met.

Chick Corea (written just before his passing and posted February 2021 on his web site): I want to thank all of those along my journey who have helped keep the music fires burning bright. It is my hope that those who have an inkling to play, write, perform, or otherwise, do so. If not for yourself then for the rest of us. It’s not only that the world needs more artists, it’s also just a lot of fun.

And to my amazing musician friends who have been like family to me as long as I’ve known you: it has been a blessing and an honor learning from and playing with all of you. My mission has always been to bring the joy of creating anywhere I could, and to have done so with all the artists that I admire so dearly—this has been the richness of my life.

PREMIERE

Joseph Alessi, trombone, and the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra (Giancarlo Guerrero, conductor) premiered the Concerto for Trombone: A Stroll in Brazil August 5, 2021, with subsequent performances August 6 (livestreamed to the world) and August 7, each before a live audience. The program also included Richard Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos, Op. 60: Symphonic Suite (arranged by D. W. Ochoa).

I and 1000 other online viewers witnessed the August 6 performance, which concluded with four bows plus an encore: Alessi and the orchestra performing again the exciting Coda of the concerto. Breathtaking as it had been to hear within the first rendition, it was astonishing to hear it reprised even after it had seemed the performers had already given their all to the work.

OSEP trombonists Alex Tartaglia and Darcio Gianelli, maestro Giancarlo Guerrero, soloist Joseph Alessi, and OSEP trombonists Darrin Milling and Wagner Polistchuk. |

|

POSTLUDE WITH JOSEPH ALESSI (September 10, 2021)

The Rehearsals & Performance

Antonio García: It’s great to see you in person; and I’m glad to know that you’re safe and sound, despite your travels to and from Brazil in this COVID era.

Joseph Alessi: Yeah, travel was a little spooky. You trust the masks and everything else; and they said that airplanes are safer than you think they are, because of the improved air circulation.

AG: Right. And how was it musically in the rehearsals in São Paulo, despite the looming virus?

JA: Oh, excellent musicians, really great people; the conductor was great. I have a lot of good friends there, including in the trombone section. I’ve known them for a while, and a lot of them went to Juilliard. The musicians were really engaged. But you know they have a lot of adverse things to deal with down there: there’s a lot of poverty. And while the vaccination rates are better than they have been, they’re generally lower than in the U.S.

Did you know they have a world-class concert hall? It was converted from a train station. I’ve played there before, a long time ago, with the New York Philharmonic. So it was great to be back. We did three performances of the concerto there, and I was very pleased with how it went.

AG: And the second of the three was the one that was broadcast online. I noticed there were 1000 viewers present! At a lot of virtual events one might see 50 or 100 people attending; so 1000 is quite a virtual concert hall.

JA: I’m glad I wasn’t watching the attendance-count rise while I was playing!

AG: We’ve hosted you here at Virginia Commonwealth University for some masterclasses and a performance in the past. When you were in Brazil, did you have opportunity in your schedule to give any master classes?

JA: We did one via Zoom before I arrived there. It had seemed a little too risky to do it in person at that point of COVID. But the orchestra members are probably all vaccinated, and they have rigorous testing in that hall. And since I’ve been vaccinated, I trust it: I wouldn’t have travelled at all if it weren’t for the vaccine. I ventured out once in Brazil with the trombone section to a very nice Italian restaurant—but we sat near the window.

AG: When I watched the performance, which I thoroughly enjoyed, I was struck by the end of the performance, which of course was the very challenging Coda of the piece. You’d mentioned to me in our last interview that you’d actually asked Chick Corea to rewrite that ending so as to be bigger and more dramatic than originally composed. But it seemed to me that you were particularly emotional at the end of the piece; and I wasn’t sure if it was entirely because of the physical and musical exertion involved or was in part because of the culmination of this great project with Chick, who had since passed.

JA: Yeah, I think was a culmination of a lot of things: for one, just being able to perform as a soloist despite the surrounding COVID. And then to be able to perform as a soloist with a great orchestra as São Paulo’s is. And to see my friends there. Then of course the project had been a long time coming since the first plans for this. And most importantly, yeah, I wished Chick were there. But you know, I was kind of hoping that he was there in spirit. It’s sad that one day you’re there, and then the next day you’re not. He had wanted to come to Brazil and to play the piano part with us. And probably at the end of the show we would have done some encore together.

I felt I’d put my heart and soul into that project; and when you finish something like that, something happens within your emotions: it’s kind of relief and joy and sadness all in one.

AG: Well, it’s no secret to you; but that comes through in the performance: the Coda of the concerto has a sense of desperation in it, a sense of revisiting and attacking a goal again and again. To play the concerto musically is enough of a challenge; but carrying the emotional perspective that you do going into it I think translates into a very broad performance, a very wonderful, evocative performance that communicates even over the Internet. And that’s a beautiful thing.

JA: That’s good. Chick had called the concerto sort of a modular piece.

AG: I remember that from our earlier chat.

JA: Right. He said, “Hey, you can do these movements in any order you want; or you can do only some of them, as a small piece.” He left that up to the performer, which was interesting to me. But I just played it in the order that he’d written it. And the orchestrator did a wonderful job.

AG: John Dickson. I saw he was on the livestream, watching. There were comments going back and forth in the chat.

JA: Excellent. Right now he’s working on a wind-band version. He has some great ideas. Professor Tom Leslie at the University of Nevada–Las Vegas is working with John to get a consortium of ensembles together, and perhaps Tom and his wind ensemble will premiere that adaptation.

AG: I recall that when I’d spoken with Chick in November 2020 I’d asked about the potential for a piano reduction; and he mentioned John’s skills towards creating such.

JA: John’s going to do that. And my wife suggested that perhaps there could be a version for soloist and chamber ensemble, or soloist and percussion.

AG: In Brazil the piece generated quite a response from the audience. You had four bows—and then the challenge and audacity of playing the Coda again.

JA: Yeah. I came up with that idea. When you go to a foreign country, it’s traditional to do an encore.

AG: Especially if you get four bows!

JA: So I had been trying to figure out what to do; and I suddenly thought that we should just do the Coda again. Why not? How could you follow the world premiere of Chick Corea’s trombone concerto with any other kind of music? So that just kind of hit me during the flight to Brazil.

AG: Wow. Given the challenge of that music, it’s something that I think most trombone soloists would not elect to do; but it made it all the more breathtaking and certainly a celebration. To hear you and the orchestra rise to that occasion twice in 15 minutes is quite an accomplishment.

JA: Thanks. And the real challenge playing down there, of course, was that everybody was spread out, socially distanced; so the brass were way far away! So that was a little tough for Giancarlo Guerrero, the conductor, to put together. But he really made his points come across in the rehearsal, and then everybody came together and did it. And I must say that the pianist was very good: I believe she was a Russian pianist living in Brazil.

AG: So how did the flow of rehearsals go?

JA: Well, there was another big piece on the program as well: the concert version of Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos, Op. 60: Symphonic Suite. It’s a bit like The Ring without words. That was a difficult piece, and the maestro did spend a lot of time on that. So when we did get to the concerto, the first reading of it was a little shaky. I’ve certainly had this happen before, where you only get 45 minutes the first rehearsal day; and you’re thinking, “Oh, my God, is this ever going to come together?”

But then the next day is better, and the next; and the musicians in the orchestra were really enjoying it. Their orchestra often performs music by Latin American composers, but they don’t get to play music such as this concerto very often. So they got into it, and everybody had a real good feeling.

AG: It’s always great to bring music and countries and people of different backgrounds together in the pursuit of expression, which this piece certainly did. And to do it in the middle of a pandemic as a collaboration across continents is quite an achievement.

The Future

AG: I believe your original plan with Chick had been that the New York Philharmonic would do the premiere; but when COVID arrived, it made more sense to renovate the NYP concert hall during that time and postpone the New York performance to a later date.

JA: It’s somewhat poetic—given that I had initially been inspired by Makoto and Chick’s performance of the tune “Brasilia” in New York—that the concerto’s premiere actually occurred in Brazil! But I just got word that May 22, 2023 will start the New York performances with our maestro, Jaap van Zweden, in the new concert hall. Prior to that I’ll be going to Portugal, with the orchestra Fundação Gulbenkian (Lisbon), who were part of the consortium. Giancarlo Guerrero, who conducted the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra for the premiere and is the music director of the Gulbenkian, will conduct that. I believe there are three performances there. I hear it’s a great orchestra; so I’m very excited about that.

Then a month later, I’ll be in Tokyo with Alan Gilbert, our NY Phil former music director, conducting the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra. Our remaining consortium orchestra is the Helsinki Philharmonic, but no date is set for that. Then there’s a possibility of our performing it with the Nashville Symphony, and there may be others. I’m really excited, of course, to perform the concerto with the New York Philharmonic. We have such amazing musicians there, and I think in New York it’s going to be well received.

It’s a moment in history: we lost this great, amazing artist, Chick Corea, who had written so many great compositions. So to have a composition written by him for the trombone is really something, and I’m just very honored to do the premiere.

And what this should tell people is that you never know if something can happen unless you go for it. Sometimes you have trepidations: “Oh, I can’t do that”; or “I can’t ask that person”; or “I wouldn’t dare do that”— but sometimes you have to dare yourself. This opportunity arose solely because of my love of Chick’s music, being inspired when I heard his music one night; and I said, “God, I should at least ask; and if somebody says ‘no,’ well, okay, at least I tried.” I’ve struck out in the past, asking for commissions from John Adams and John Williams; but this one worked.

|

Chick Corea |

AG: So you just took on this big project, and now you’re going to live with it for a little while. I understand the concerto will be available for rental at some point after your New York Philharmonic performance. But what’s next in the Alessi “big project” pile?

JA: That’s a good question. I don’t have any big projects ahead right now. Maybe I need to come up with something. I’m involved with the group “Slide Monsters,” a trombone quartet with Eijiro Nakagawa, Marshall Gilkes, and Brandt Attema. We put out an album, SLIDE MONSTERS, that was very well received; and our second one, TRAVELERS, was just released. That group is in its infancy. We did one tour in Japan, and it was a huge success; so I imagine there’ll be more performances with that group once we get past COVID.

But I’m pretty happy right now. Things will unfold naturally. And I’m most excited right now about my students. At this time we’ve resumed in-person teaching. The class is quite something, a good group of people; so I’m very excited to work with them. That keeps me going for the time being because I learn a lot from these kids: they’re so good.

AG: Teaching in the COVID era is a journey. We want to have live music back for everyone, especially for our students. We want them to have the future they deserve.

JA: Absolutely.

AG: I’m grateful for your time.

JA: Thank you, Tony.

AG: In my interview of Chick Corea on November 10, 2020, he had stated: “...right when I was writing that first movement, I thought of something that I’ve never really done—which maybe next lifetime I’ll get around to—which is to start walking from way uptown in the Bronx and connect with Broadway, and just stroll all the way down Broadway to as far south as I can go.”

Look for him there.

————————————-(begin sidebar)—————————————

Web Sites

The Performance

Joseph Alessi, trombone, and the Orquestra Sinfônica do Estado de São Paulo (OSEP), August 6, 2021

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=deRUPDy_Xnk (or search YouTube for “Corea trombone concerto”). Scroll to 1’10’00 and onward.

The Artists

Joseph Alessi, trombone

https://www.slidearea.com

São Paulo Symphony Orchestra: Orquestra Sinfônica do Estado de São Paulo (OSEP), Giancarlo Guerrero, conductor

Chick Corea, composer

John Dickson, orchestrator

Tentative Schedule of Concerto Performances

August 2021: São Paulo Symphony Orchestra

May 2022: Fundação Gulbenkian (Lisbon)

June 2022: Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra (Tokyo)

May 22, 2023: New York Philharmonic

TBA: Helsinki Philharmonic

————————————-(end sidebar)—————————————