|

The Virginia Commonwealth University Jazz Orchestra I, performing under the direction of Antonio García, Director of Jazz Studies. |

This article was published as García, Antonio J. “Running an Efficient and Effective Big Band Soundcheck.” Jazz Education in Research and Practice, vol. 1, no. 1, 2020, pp. 201–206. JSTOR. The Author may post a preprint version of the Contribution on personal websites and in-home institutional repositories (IR). A preprint is the version of the article that is sent to a journal editor after review and revision but before copy editing. Therefore the preprint version shown here is a “working paper.” Several demonstration videos have also been added to this online version in order to bring the educational concepts to life. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or distributed in any form, by any means, electronic, mechanical, photographic, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Indiana University Press. For education reuse, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center. For all other permissions, contact IU Press. |

Running an Efficient and Effective Big-Band Soundcheck

by Antonio J. García

ABSTRACT Keywords: soundcheck, mic, bass, house, monitor |

|

The Virginia Commonwealth University Jazz Orchestra I, performing under the direction of Antonio García, Director of Jazz Studies. |

As a college student I had the privilege of playing in the school jazz ensemble with legendary drummer Mel Lewis as guest artist. My chair in the band was far from the rhythm section, and there were no monitors. During the dress rehearsal’s break we were talking when he asked me if the rehearsal was going well for me. I replied, “Well, I can’t really hear the bass.”

He asked, “Can you feel it from where you are?” “Yes, I believe so,” I answered. “Well,” Mel scoffed lovingly, “What the @#$%! else do you WANT? It’s not a @#$%! home stereo! If we turn up the bass loud enough for you to hear it, it’ll ruin the sound for the audience!” It made perfect sense then, when we played Thad Jones’s “Cherry Juice” at warp speed and “First Love Song” so pensively; and it still does. All too often from the audience I hear bass “boom” dominating the stage.

I’ll detail below my

approach to big-band soundchecks, since so many of my guest artists comment that

it produces fine results within a half hour and is different than many. I have

to say it’s great when we play a hall that needs no sound -reinforcement,

or perhaps only a single solo mic. Our hall is not so. Not all halls have professional engineers. Moreover, having a pro soundperson is not a

cure-all: being a great engineer does not immediately bestow awareness as to

how a big band should sound; more often than not, I have found that the engineer

at a given venue is much more familiar with pop or rock music.

It

is critical that a band director know and advise the sound staffer (pro or

volunteer) as to what the director wants and then advocate for that result as

needed. This is not an adversarial relationship. Just as in an independent

recording studio the engineer serves the artist, in a live concert the engineer

serves the band director. And just as a pro band might need little direction

from its leader in concert, a pro engineer (if familiar with the expressive

sound of a big jazz band) may need little guidance. Conversely, a novice band

will require significant on-stage leadership; and an engineer unfamiliar with

your vision of big -band sound will need your

guidance.

Setting the Stage

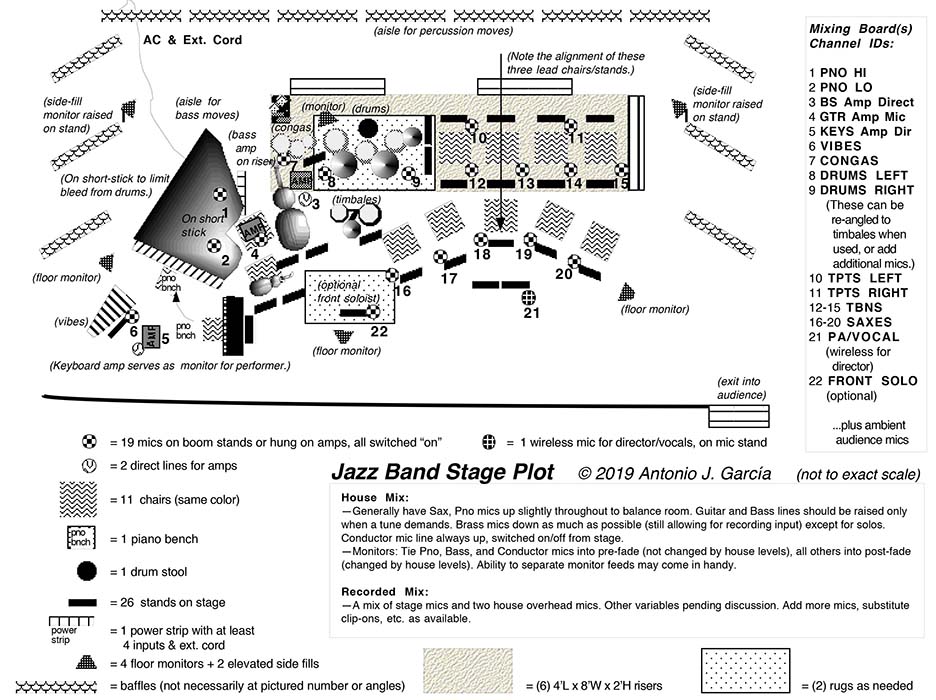

My context here is a stage

on which I have five saxophone mics, 4-5 four to five trombone mics, two trumpet mics (spread

across the section),; amplified rhythm section,; a PA (public -address)

mic for the director (and possible vocalist),; and monitors for piano, drums, and perhaps front-left and -right of the winds—if

not also elevated side-fill monitors that benefit the back rows of musicians. I

illustrate this within the following stage plot that I provide my engineer and that which several of my guests have sought from me

for their own future reference. You’ll note that the sax section is curved so

that members can better hear each other’s direct sound; I do the same in

rehearsal.

|

I provide such a plot in

advance to my hosts when I am contracted to direct an all-state or all-district

band, noting that I recognize various elements may not be possible. It ensures

that the band will rehearse in a similar

configuration to its performance -stage (as rehearsals are

rarely held in the concert hall). It is also important

to provide your engineer with a clear vision as to what you, as director, seek. Too often sound -staff

have to interpret unclear statements from musicians, such as, “I need a big -band setup.” Provide clarity if you want it

in return.

Click on this image to see a time-lapse video of Curt and student crew #1 setting up piano, risers, chairs, stands, mic booms, and monitors during approximately a 30-minute period. Video courtesy Curt Blankenship. |

Click on this image to see a time-lapse video of Curt and student crew #2 setting up percussion, amps, and all cables during approximately a 30-minute period. Video courtesy Curt Blankenship. |

After all risers, chairs,

stands, mics, monitors (audio feed to the performers), house sound (audio feed

to the audience), instruments, and musicians are in place—yet no audio

lines have been checked—we begin our sound check -clock.

Prep

Ask your sax and trombone section -leaders to choose a voiced passage (either a

soli or a moving-line background) for later use. Also have them choose one

well-voiced chord from that passage as a test -fermata

for later. (If you have mics on each of your trumpets, rather than just two, have

them do the same.) Ensure that the feed into the monitors from your

PA mic (wireless, so that later you can go listen from the audience -seats) is at a comfortable level. On stage,

demonstrate good horn-mic technique and bad. I speak to the band with my

wireless mic parallel to the ground, about an inch from my mouth (a good start

for vocalists). While continuing to speak, I tilt the mic so that it’s

perpendicular to the ground, which narrows the frequency response considerably.

Then I return the mic to parallel to the ground but start moving it left and

right of my mouth, showing how directional the mics are, reminding them that the performance

and resulting recording of their solos is going to sound just that awful if they do the same. I ask horn -players

to position the mic about 3-4three to four inches from

their bells if playing at a medium volume, tilting themselves away more if

playing much louder. I mic the flutes at the nose of the player, close, perhaps

at a slight downward tilt.

That explained, it’s time to begin actual

sounds. Temporarily turn off all input to the monitors and house sound except

for your PA mic. There’s no need to run anything else into the monitor -feeds until you know what sound is going to

bounce back from the house speakers (which have not yet been sound checked).

Click on this image to see a real-time video of Curt, the author, and the student ensemble complete an effective soundcheck within a 30-minute period. |

Sounds

photo credit

Steven Casanova |

|

House

Once you’re satisfied, then slowly add the rest

of the rhythm section: guitar soloing and, then later on your cue, comping “Freddie Green” style (not loudly); adding piano soloist, then

comping; adding drum -time. Get the house -balance to present a clear rhythm section

without boom or clutter.

Add your first sax -player

(perhaps audience left, my first tenor) as a soloist on top of the rhythm

section while you and the engineer chat to EQ that house channel to

satisfaction. (You may reverse horn sections, setting bass bone and bari sax

near the rhythm section, if you prefer.) Shift to the next saxist, repeating

the process, then moving on to various brass soloists.

Monitors

If you’re pleased with the rhythm-plus-individual-soloist

house sound, return to the stage; and turn on the monitors to join the house

sound that’s already in play. Repeat the entire sequence for the benefit of monitor -feeds: start with the bass walking F blues,

and check the feed in each monitor by your walking (or that of a trusted

colleague) to each one. Use a thumbs-up or thumbs-down when possible to cue

your engineer for any adjustments; if you must speak, refer to percentages of

change.

Add the members of the rhythm section one-by-one while checking with the other rhythm members—especially

your drummer—to ensure s/he hears what s/he needs to hear. (Ask performers

to offer you hand -signals in lieu of

speaking if possible.) Check each solo horn- and rhythm -mic

on top of the rhythm section, ensuring that all bandmembers can properly hear

the soloists. Jazz largely ceases to be jazz the moment participants can’t hear

each other! When satisfied, stop the band; and return to the

audience’s seats.

|

photo credit

Steven Casanova

|

Balance

Having checked the audio lines sufficiently, it’s

now time to check the balance of

those lines. Have the sax section play a “pyramid” of the

five-tone chord its section -leader chose as a fermata -test, from the bottom up. Players must do so at performance volume and at equal stage -volume

to one another; or the test is pointless. In a typical voicing, that means that the bari plays

its note, two seconds later adding second tenor, two seconds later first tenor,

two seconds later second alto, and two seconds later lead alto, completing the

chord. Since they supposedly played at equal stage -volume

and with good mic placement, you have to determine from the audience if you’re

hearing a balanced chord. If not, change house levels accordingly. Once you

like the levels, have the saxes play their soli passage; again adjust as

needed.

Repeat the pyramid- and soli -processes

with the bones (later with trumpets if there are four to five mics rather than two). Return to the stage, and run a partial chart to ensure that the monitor -balance on stage is practical for the

members. Tend to any front-solo mics, including

vocalist(s), to conclude your line- and balance -checks.

Timing

I can usually complete the

above checks for house and monitors in a half hour and am then ready to run excerpts

of pieces as needed, focusing on unusual passages the engineer should hear (mutes,

woodwind doubles, electronics, front soloists) and/or with which the performers

need familiarity on this stage. During this time I continue to fine-tune the

monitor- and house -sound. If your soundboard is automated, your

engineer may be able to save your current concert audio-setting as a “scene” (an electronic snapshot

allowing later instant -recall of the digital

environment) so that next concert you won’t have to mix from scratch.

Wrap-Up

Look

out for your sound engineer, who is an

instrument within your ensemble’s sound. I provide a cue sheet for all

solos, critical mutes/doubles, and electronics per tune, including cues to turn

the house sound down or even off for certain tunes. Optionally I can provide a

producer to cue the engineer. I assign crews from the performing students; they

assist setup and teardown. Annually I demonstrate proper cable-wrapping

technique so that that job

gets done right. And every concert I spotlight the engineer for recognition by

the audience. My university’s engineer [Curt Blankenship] is superb and actually has never missed

a large or small jazz ensemble concert during my career here!

I

thank my own mentors and colleagues, formal and informal, for their guidance in

forming my perspective on big -band sound checks.

|

The Virginia Commonwealth University Jazz Orchestra I, performing under the direction of Antonio García, Director of Jazz Studies. |

Selected Listening

Swing

Count Basie Orchestra. (1994). The complete atomic Basie [CD]. Los Angeles, CA: Blue Note (Original

album released 1958)

Sinatra, F. (1998). Sinatra at the Sands [CD]. Los Angeles, CA: Warner Brothers. Original album released 1966

Latin/Brazilian

Various

Artists. (1992). Bossa nova Brazil [CD]. Santa Monica, CA: Verve.

Various

Artists. (1992). Samba Brazil [CD]. Santa Monica, CA: Verve.

Latin/Afro-Cuban

H.M.A. Salsa/Jazz Orchestra. (1991). California salsa [CD]. New

Orleans, LA: —Sea

Breeze CDSB-110 (1991).

Mambo All-Stars on Various Artists. (2000).,The mambo kings [CD]. New York, NY: Elektra 62505. (Original album released 1992.

Funk

Earth, Wind & Fire. (1998). Greatest hits [CD]. New York, NY: Sony.

Tower of Power. (2001). The very best of Tower of Power: The Warner years.Los Angeles, CA: Rhino/WEA.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic, chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh, Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. One of his recent commissions was performed at Carnegie Hall by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra.

A Conn-Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist, bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins: Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer, he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Most of all, Tony is dedicated to assisting musicians towards finding their joy. His 35-year full-time teaching career and countless residencies in schools have touched tens of thousands of students in Canada, Europe, South Africa, Australia, The Middle East, and across the U.S. His collaborations highlighting jazz and social justice have raised hundreds of thousands of dollars, providing education to students and financial support to African American, Latinx, LGBTQ+, and Veterans communities, children’s medical aid, and women in jazz. He serves as a Research Faculty Member at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. His partnerships with South Africa focusing on racism and healing resulted in his performing at the Nelson Mandela National Memorial Service in D.C. in 2013. He also fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program.

Mr. García is the Past Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal. He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His book Cutting the Changes: Jazz Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he served as Editor of the Jazz Education Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997 Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson, “The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes: “Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s “splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing” and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and “first-class writing of special interest.” The Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely” composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

Tony is the Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute. The partnership he created between VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz Improv; Music, Inc.; The International Musician; The Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards. Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of 434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Arts’ 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service, in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame, and is a 2023 recipient of The Midwest Clinic's Medal of Honor. Visit his web site at <www.garciamusic.com>.

If you entered this page via a

search engine and would like to visit more of this site,