Tribute

to Richard Erb, Arnold Jacobs, George Osborn, John Marcellus

Posted on: 1/7/2007

at <http://www.midwestclinic.org/mentortribute/tribute.asp?tributepostId=18>.

As

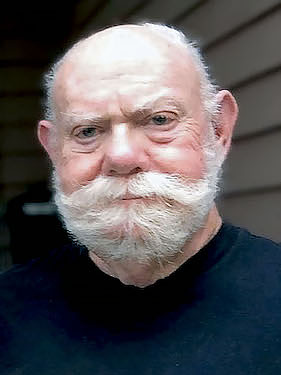

an undergraduate, I focused on tenor trombone. Richard Erb was bass trombonist

with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra and on the faculty at Loyola University

of the South, where I studied with him. He had the most profound effect of

all my wonderful trombone teachers on my playing skills—and a world of

patience. It helped, I think, that in his youth some of his teachers

had told him he would never make it as a professional trombonist.

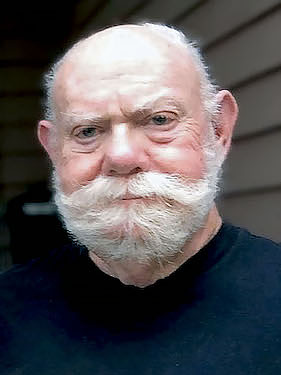

Arnold

Jacobs, the late tubaist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was Erb's most

profound teacher, to whom Dick had sent me when I was struggling the most.

In one hour, Jacobs permanently changed my playing for the better. (He would

say, of course, that I made the change; but I could not have without him.)

Needless to say, I returned for more hours! And then my lessons with Dick

entered the new possibilities we had hoped for.

In

graduate school I focused my classical studies on the bass trombone and kept

the tenor my jazz focus. I was fortunate to have George Osborn as my private

trombone teacher at The Eastman School. He, too, exhibited great patience

with this jazz-writing graduate student. I kicked myself into preparing as

much as possible; but sometimes the exhaustion of the jazz-writing major would

take over—such as when I actually feel asleep once in a lesson while

standing up and holding the trombone! George taught me a tremendous amount;

so I must have been awake most of the time.

John

Marcellus directed the Eastman Trombone Choir and the (jazz) Bionic Bones. He has always been a champion of all music: jazz, classical,

and contemporary—large and small ensemble—and he addresses each

with ease (and of course, his notoriously active sense of humor). I experienced

some of my most profound performance-related emotions under his baton as he

elicited the music from our bells.

Without

the mentorship of these fine folks, I would certainly not be playing the trombone

today.

|

|

|

|

John Mahoney |

Manny Albam |

Rayburn Wright |

Bill Dobbins |

Tribute

to John Mahoney, Manny Albam, Rayburn Wright, Bill Dobbins

at <http://www.midwestclinic.org/mentortribute/tribute.asp?tributepostId=19>

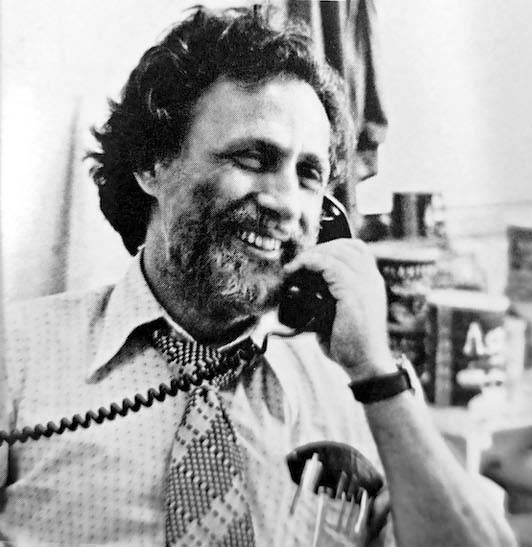

John

Mahoney was Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Loyola University of the South from 1978 until his retirement in May 2014. During his earliest years there I studied jazz improvisation and writing with him. A trombonist, pianist,

composer, educator, and sometimes-vocalist, his background is a large influence

on those elements ending up in my background. Despite my slow learning

as an undergraduate jazz trombonist, John realized that I had some abilities

as a jazz writer and told me so (as I had not recognized that avenue myself).

With a little extra time, I was able to get my act together enough to get

into Eastman as a graduate jazz-writing major.

Part

of that extra time was a month at Eastman’s summer “Arranger’s

Holiday” Institute, where I experienced the joy of surrounding myself

with musicians who so intensely wanted to perform and write music—and

on a tight schedule. My primary writing instructor there was Manny Albam,

who exposed me to music and a means to write it that literally changed my

life. Anytime he taught or conducted, he subliminally conveyed to everyone

how happy this life of music made him and how much he wanted to share it with

us, to bring the next generation into this great feast. And he did, year after

year.

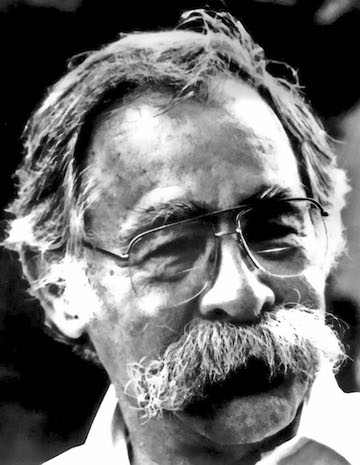

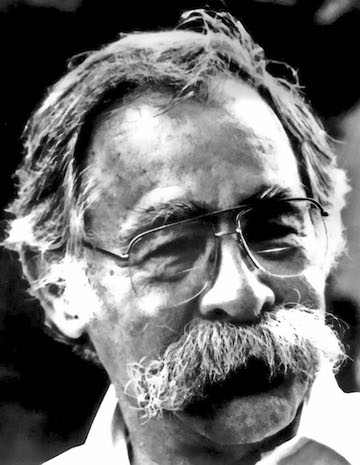

Once

a full-time student at Eastman I had the opportunity to study under Rayburn

Wright, the late Director of Jazz Studies at the Eastman School of Music.

I had gotten a week or so with him a previous summer. What a mind! What ears!

What leadership! What interpersonal skills! What organizational chops! What

a visionary! What a teacher! What a nice guy! To say he taught by example

is an incredibly unsatisfying understatement. He was wildly capable of anything

musical and accomplished it with a calmness that belied his abilities and

his enthusiasm. I could live, learn, and teach the rest of my life and never

rise to Ray’s abilities as a mentor and person; but there’s good

reason to try. You can read an article I wrote in tribute to him here.

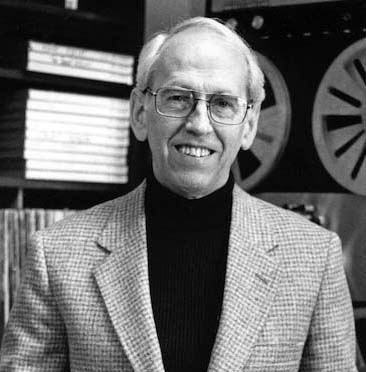

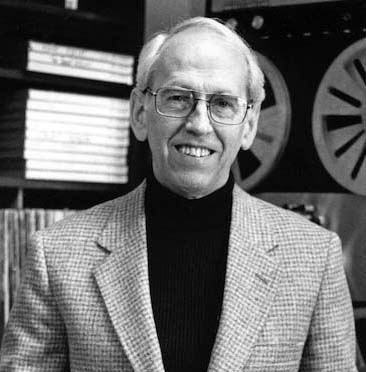

His

colleague, Bill Dobbins, taught there for many years further. I had thought that John Mahoney

was the picture of laid-back until I met Bill (who, along with Ray, had taught

John). Bill’s determination and focus made any musical task achievable,

and he expected his students to apply those same skills to the best of their

abilities. His ears and notation accurate beyond any standard, it’s

fair to say that the question “WWBD?” (“what would Bill

do”) arises at least subconsciously every time I decide how best to

write out some ridiculously intricate transcribed passage. His instructional

and performance abilities alone were enough to make the Eastman

experience worthwhile; but partnered with Ray, those two years were an unforgettable

recipe for my learning how to write, (finally) how to improvise, and in what

ways I wanted music to be in my life.

These

people were of critical importance in bringing my abilities to flourish—especially

as a writer, but also as a performer, and most certainly as a teacher.

|

|

|

|

Joseph Hebert |

Patrick McCarty |

Marion Caluda |

Logan Boudreaux |

Tribute

to Joseph Hebert, Patrick McCarty, Marion Caluda, Logan Boudreaux

at <http://www.midwestclinic.org/mentortribute/tribute.asp?tributepostId=20>

At

Loyola University of the South, Dr. Joseph Hebert directed the Wind Ensemble until retiring in May 2015. During much of that time, he also ran the jazz program he had

founded there (before passing it to John Mahoney). But I had first experienced

him via the Loyola Summer Music program, where my older brother and then I

had attended during high school. So in various ways, I had learned from him

during my elementary, high school, and college years. The artists he brought

in and tours he led were also important experiences in my life.

After

I found I could not yet get into my chosen graduate school, he offered me

the chance to take an extra year of study at Loyola in order to further my

abilities—an opportunity that certainly opened a door to my future. Then,

in the summer between grad-school years, when I visited home to see if I could

find musical work to pay my school bills, he promptly offered me a steady

gig of major proportions that exceeded any hopes I'd had. "Doc"

always found the intersections of need and opportunity, which inspires the

rest of us to make the most of them and to create them for others.

Another

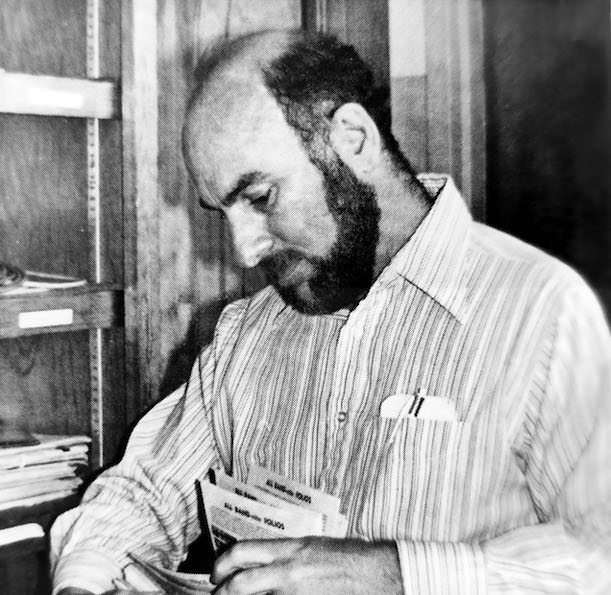

"Doc" had similar impact. Dr. Patrick McCarty taught music theory

for the Loyola Summer Music program during my high school years, where he

opened up my eyes to a fascination with scores, parts, and their aural sum.

When I later majored in music there, he was my freshman theory teacher. I'd

often turn in two versions of the homework: one that I knew was what he was

seeking, and one that included the uncategorized sounds I was hearing in my

head for the exercise. He'd patiently correct each, showing me the theoretical

names and processes for what I was hearing—often jazz influences I could

not yet identify on my own. I still remember his red, blue, green, and purple

inks for marking various musical characteristics. (Note the many pens and markers in his photo above!)

These

two professors intersected frequently in my high school years. In fact, Dr.

Hebert directed me within the All-District Concert Band in my senior high

school year, for which the repertoire included "Ballade," written

by Dr. McCarty. It's still one of my favorite wind ensemble compositions;

so I'm holding onto the LP.

The

teaching of both "Docs" reinforced my belief that it's important

to have some of the most experienced instructors teaching the youngest students.

They set me on a path and steered me through years of efforts to find my creative

voice.

Certainly

that path had its roots at Jesuit High School. When I was a junior, I asked

my band director, Mr. Marion Caluda, if I could re-arrange a concert band

arrangement of "Sounds of the Carpenters" so that it might become

a feature for our trombone section. His consent provided me score-study and

some writing practice. And of course I played the trombone in any configurations

I could find at school. In my senior year he allowed me to solo with the marching band on the football field on "A Fifth of Beethoven." I recall in the first rehearsal finding that I'd not transposed the original trumpet-key chord changes into concert key for my own use. Lesson learned!

In

my junior year his colleague, Mr. Logan Boudreaux, formed a coalition with nearby Dominican High School so as to form a coed jazz band that served the interests of both schools. In my senior year he formed the first Jesuit

jazz band in many years; and we managed to get our act together enough to

perform at the Loyola Jazz Festival, which I had attended as a spectator for

years. Such opportunities sparked my interest in a life of music-making, and

I am indeed fortunate that he and Marion Caluda were able to give me those opportunities.

Additional Tribute

to John Marcellus

created February 2014 in anticipation of his retirement from The Eastman School after 36 years of dedicated service

During my years Doc directed the Eastman Trombone Choir and the Bionic Bones. He has always been a champion of all music: jazz, classical, and contemporary—large and small ensemble—and he addresses each with ease (and of course, his notoriously active sense of humor). I experienced some of my most profound performance-related emotions under his baton as he elicited the music from our bells.

One unique moment still stands out, nearly 30 years later. The Trombone Choir was warming up in the Remington Room when one by one, each of us felt a tug on our tuning slides behind us. Startled, I looked back to find Doc pulling out my tuning slide out a couple of inches; then he'd move on to the next person, equally surprised.

He then stood on the podium, named the Bach chorale of choice, and led us in performing the sound that only 20+ trombones can produce. But this day this sound was incredibly different: it was as one; it was dark; it was richer than ever; it vibrated throughout my body. And it was moving: I was speechless and nearly in tears when we completed the chorale; and I was not alone. It was the only time in my two years at Eastman that I fully experienced the sound I'd heard on the classic recordings of the Remington-era Eastman Trombone Choir.

What had just happened? We were all stunned. Doc simply said: "For once, no one was above the pitch. And for once, everybody knew they were out of tune; no one assumed they were in tune. So as a result, everyone listened and adjusted the way we always should."

I admit I thought the Choir should have its slides pulled for the remainder of the year, but Doc said that would have been harmful to our chops. Nonetheless, he had made his point. And time and time again, as a director of ensembles of all sizes, instrumentations, and genres, I have re-proven his point. Great music is often greater when no one is above the pitch and no one assumes their tuning is done.

Thanks, Doc, for one of a thousand great lessons. And best to you for your retirement!

I was also fortunate that because of my constant gigging in New Orleans, my subsequent performing and teaching around the world, and my 35-year full-time university teaching career

that included hiring eminent guest artists, I was also mentored by thousands of non-male and non-white musicians who also provided me invaluable and diverse guidance by their words and music.