|

This article

is copyright 2006 by Antonio J. García and originally was published

in the International Association for Jazz Education Jazz Education

Journal, Vol. 39, No. 3, December

2006. It is used by permission of the author and, as needed, the publication.

Some text variations may occur between the print version and that below.

All international rights remain reserved; it is not for further reproduction

without written consent.

|

(This

version of the article is expanded beyond that which appears in the December

2006 JEJ.

IAJE had published this extended online version in recognition of

the public's need for in-depth information on this topic—

the first and only time that IAJE published an expanded web version of a print

article from its Journal.)

Jazz

Education in New Orleans, Post-Katrina

by

Antonio J. García

|

|

The then-office of

Basin Street Records on Canal Street in New Orleans, about two weeks

after Katrina and the subsequent flooding.

Photo credit: Will Samuels

|

The gutted interior of

Basin Street Records on Canal Street in New Orleans. Mark Samuels had

to let the property go and has since moved operations to his home's

also-flooded but now gutted basement.

Photo credit: Will Samuels

|

This is a different sort of article for me to write, as New Orleans

is my native home, where I lived for 25 years. As most of us, I have seen

on television the devastation left by Hurricane Katrina. As some of us, I

have visited New Orleans since that disaster and seen family and friends.

Being there amid the utter destruction and then—a few minutes’

drive away—also walking through the active and beautiful parts of a

city that still lives is an experience television of course cannot convey.[1]

The status of jazz education in New Orleans

is its own story—and in my view, a very interesting one. It is entwined

with the wider music-ed system (both public and parochial), affected by the

informal mentorship of street musicians, focused by the sound of school marching

bands, and utterly enmeshed in the future opportunities and challenges of

the city itself.

My goal here is to share with you the

many facets that affect jazz education in New Orleans and therefore the future

of jazz in New Orleans—and therefore the future of the roots of jazz

anywhere. For there are few genres of jazz unaffected by the language formed

by New Orleans jazz musicians, not just of last century but also of this one.

I will share residents’ own words with you in an apolitical—yet

politically engaging—manner. This tale will not be all gloom and doom:

there will be proven avenues of assistance and growth and recommendations

for the future. As I write this, I am listening to the live performance of

the Treme (pronounced “trah-MAY”) Brass Band at the National Folk

Festival in my adopted hometown of Richmond, Virginia. The band, a 2006 National

Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship Recipient, had members

scattered throughout Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana who are still facing

the reconstruction of their personal and professional lives. But their sound

remains glorious and uplifting, as does the spirit of New Orleans itself.

I

hope that through this article I have found a way to provide you, as a member

of the global jazz community, added reason to care and to act in any positive

direction you can.

Hurricane Katrina made landfall on Monday, August 29, 2005, as

a Category 4 hurricane.... The levee breaches flooded up to 80% of the city,

with water in some places as high as 25 feet. The storm and flooding took

over 1,500 lives and displaced an estimated 700,000 residents.... Nearly

228,000 homes and apartments in New Orleans were flooded, including 39%

of all owner-occupied units and 56% of all rental units. Approximately 204,700

housing units in Louisiana either were destroyed or sustained major damage.

As of April 2006, 360,000 Louisiana residents remained displaced outside

the state. Some 61,900 people were living in FEMA trailers and mobile homes.[2]

Formal

K-12 Public Education in New Orleans

When I first started teaching in 1975, there

were many band directors who played nightly engagements. They were outstanding

educators in many regards because they were outstanding musicians who carried

forth their professionalism from the bandstand into their teaching.

But music education in Orleans Parish schools has been lacking

tremendously the last ten years. Therefore, [public-school formal] jazz education

was almost non-existent. Parents hardly ever buy their child an instrument

any more and very rarely invest in private lessons; and today’s band

directors are too caught up in marching band, neglecting concert band and

jazz band.

—Joseph

Torregano, Director of Bands, East St. John High School

in Reserve, Louisiana.[3]

Truth be told, in the past ten years, the corrupt and dysfunctional

public school system had begun to shirk one of its most critical roles—serving

as one of our most important cultural incubators (the other major source being

our church choirs). The School Board let our Master band directors go, many

of whom were part of music-family dynasties, where our traditions had been

handed down from father-to-son through generations. Somewhere in the ’80s

or ’90s the slide started. Public school music programs were cut back.

Music instructors of undetermined qualifications and little accountability

were assigned to multiple schools with no fixed band rooms.

—David

Freedman, General Manager, community radio station

WWOZ-FM.[4]

The big reality is that there’s not too much of a difference

between what’s going on with jazz education in New Orleans versus what’s

going on with overall education in New Orleans. There’s a major restructuring

of the schools; we’re starting over fresh. Nobody would say that the

educational system was great before. But the cultural aspect had come from

people’s houses and high school band rooms: you could be a kid in New

Orleans and be in six different bands. That’s not here anymore. We’re

going to feel the effects of this change five or six years from now.

—Irvin

Mayfield, Founder and Artistic Director of the New Orleans

Jazz Orchestra, Inc.[5]

Before the hurricane the Orleans Parish School Board administered 120

schools. This year...five.

—Guy

Wood, Music Educator, District VI (New Orleans).[6]

Thousands of schoolchildren across the Gulf

Coast were displaced by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The storms hit just before

the start of the 2005-2006 school year.... In the areas of Alabama, Mississippi

and Louisiana affected by Katrina, there were 419 rural schools with nearly

220,000 students, most eligible for federally subsidized meals and about one-third

of them African-American....

In New Orleans, an issue of concern for many

parents of public school children is the post-storm increase in controversial

charter schools. Of the 57 schools slated to open in Louisiana’s State

Recovery School District this fall, only five are traditional public schools

overseen by an accountable and elected school board. The other 53 are charter

schools, which receive both federal and state dollars but operate with more

autonomy and, some say, little accountability to the local communities they

serve.

Some education officials are enthusiastic about the trend. Orleans

Parish school board president Phyllis Landrieu has called the charter phenomenon

“a cause for celebration” that gives students and parents a wide

choice of educational options.[7]

The government is also embracing charters. Since the storms, Louisiana

charter schools have received at least $44 million dollars in federal assistance.

Furthermore, state legislation passed last year allowing Louisiana to take

control of local school districts also eases restrictions on charter schools,

a move that could further damage an already struggling public education system.[8]

With this takeover, the public schools in New Orleans are currently

operated under one of four umbrellas: the Louisiana Department of Education

(through its Recovery School District); the Orleans Parish School System;

the Algiers Charter School Association; and additional, independent schools

chartered by either the Orleans Parish School System or the state-run Recovery

School District.[9]

This did not occur without great controversy:

Less than a month after Katrina devastated

New Orleans, the city’s already struggling public education system was

dealt a devastating blow by the Louisiana state legislature. In October [2005],

state lawmakers voted to take over New Orleans public schools, a process that

allowed the Orleans Parish School Board to fire 7,500 school employees from

their jobs, including nearly 4,000 teachers. No advance notice was given before

the decision was made public; so most of these employees only learned about

their terminations through the media....

To add insult to injury, under the state-administered Katrina recovery

school district, control over many New Orleans public schools was granted

to charter organizations. In addition, federal Secretary of Education Margaret

Spellings announced that $24 million dollars of federal funds was granted

to Louisiana by the Department of Education for the express purpose of supporting

charter schools, while traditional public schools received nothing. Parents

and teachers alike express grave concerns about the future of public education

and what the current push for charter schools means for standards, fairness,

and accountability in education.[10]

Some

see the move as being a very positive one:

“We see an opportunity to do something incredible” [said]

Governor Kathleen Babineaux Blanco.... And she just may be right. Education

could be one of the bright spots in New Orleans’ recovery effort, which

may even establish a new model for school districts nationally.... But in

the first three years or so after the hurricane, K-12 education in New Orleans

will be a trailing phenomenon, dependent on how fast the economy and housing

are rebuilt.[11]

By the end of December [2005], there were approximately 2,000 students

in six public schools in Orleans.... By July 31, the last day of the 2006

spring semester, ...the Orleans school district included five schools being

operated by the District office and 12 charters, and was accommodating over

6,000 students. Combined with the Algiers Charter Schools and the State Recovery

District, there were nearly 12,000 children in 25 public schools in New Orleans.[12]

The rising student numbers did not restrain interest in protesting

the manner in which educators and staff had been fired; they filed a lawsuit

against the state in September 2006:

Renee F. Smith, an attorney for the school board, said the teachers

and staff had to be fired. Otherwise, she said, it would have amounted to

the district paying them for work they did not do.... Darryl Kilbert, acting

superintendent of New Orleans Public Schools, testified Friday that the Orleans

Parish district only employs about one-tenth of the workers it had before

Katrina. And, he said, it cannot afford to hire more.[13]

Meanwhile, without even its previous level of infrastructure and most especially

without many of its educators, formal jazz education in the K-12 public system

has all but disappeared:

Pre-Katrina there were jazz education programs in six public

schools.... Post-Katrina, jazz education is non-existent.... The lack of success

is truly due to the sad state of education in New Orleans. The educational

landscape in New Orleans is probably more difficult to navigate then the surface

of the moon. Currently there are public schools, state-run schools, state-charter

schools, independent-charter schools, parochial schools, and private schools—all

working uncooperatively.

For a complete year after Katrina, there was almost no music

education in New Orleans area schools. I am afraid that we are seeing the

possible loss to an entire generation of the oral traditions of jazz that

have been passed down for years, allowing New Orleans music to exist. We could

see a generation with no concept of tradition, history, art, or culture. I

had accepted the position of Music Coordinator for New Orleans Public Schools

with the intent to reorganize and reinstitute music education as an inclusive,

interdisciplinary course.

—Brice

Miller, the recent Coordinator of Music Programs for

New Orleans Public Schools and the Artistic Director/CEO of the New Orleans

Jazz Education Foundation.[14]

NOCCA

The New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts has long been a beacon for area

arts education at the pre-college level. Well-known for such

|

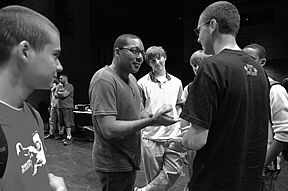

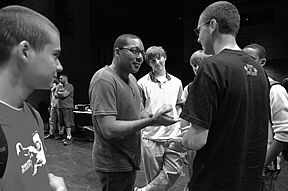

Wynton Marsalis mixes

with NOCCA students at an open rehearsal of the Lincoln Center Jazz

Orchestra in New Orleans.

Photo credit: Elizabeth

McMillan

|

former

students’ names such as Marsalis, Connick, Blanchard, and Harrison,

its facility benefited from the wisdom of the city’s founder, Jean Baptiste

Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, who in 1718 had the foresight to build the old

city of New Orleans on some of the area’s highest ground.

“Fortunately NOCCA is very healthy at the moment,” assures

Michael Pellera, NOCCA’s Jazz Department Chair. “We are back to

our pre-Katrina numbers. Of course we did not have a fall semester in 2005,

and we operated at a satellite site in the spring at about half of our pre-Katrina

numbers. Some students participated online and returned for an intensive,

five-week summer program.”[15]

But, says NOCCA Chair Michael Rihner, there are notable downsides to the fiscal

and musical foundations of this institution long known for its diversity in

musical instruction:

NOCCA’s budget was slashed by the State for a while.

Though it has come back to a good degree, we lost funding for our part-time

faculty teaching private lessons. So now students have to come up with their

own means to pay for outside lessons (though there are a few grants).

Equally challenging is the pool of qualified teachers: there

are not as many available. So we have a difficult time identifying and recommending

instructors to students in some specific areas. Many musicians who used to

live here have nowhere to live in town and so have not returned.

Katrina has definitely affected our student demographics and

thus our students’ musical background. For example, thirty to forty

percent of NOCCA’s students used to be from the inner city of New Orleans,

bringing a background of the city’s famed street-sound into our institution.

That has greatly declined, and the student body has a more suburban feeling.

Forty percent of our freshman class used to be African American: now it’s

five to ten percent.

That’s a significant change, and it affects

the musical landscape for the students. We always had a mix of students from

the “Treme Brass Band” tradition; now we have very few brass students

and a high number of white, middle-class guitar students.[16]

The New Orleans parochial school system, which educated 40 percent

of New Orleans’ students, was also devastated. Although Catholic schools

have reopened in some of the highest and driest neighborhoods and some damaged

schools elsewhere are reopening, it is not clear whether or when all the flooded

schools will open. But because the archdiocese includes all the parishes in

New Orleans, not just Orleans Parish, many of the students in the hardest-hit

schools were reassigned to other schools outside the central city.... Overall,

79 percent of Catholic school students have returned to class.[17]

The Catholic administrative system was better suited to meet the challenge

of the displaced students, as the pre-Katrina needs of Baton Rouge and New

Orleans had already resided under one roof. And the Catholic music programs

had often been better funded than their secular counterparts. “Students

responded very well to being back in music, establishing some normalcy in

their lives. The ones that came to Baton Rouge from New Orleans were absorbed

at no charge,” explained Sister Mary Hilary, O.P. As the Director of

Instrumental Music for the New Orleans and Baton Rouge Dioceses, she is responsible

for the 35 schools in the two regions. “But our biggest challenge is

replacing the students’ personal instruments lost to Katrina.”[18]

Has the influx of students and families from New Orleans affected music education

in Baton Rouge? “I do not see a difference,” states Duane LeBlanc, the Director of Bands at Catholic High School.

“Baton Rouge has had a strong history of jazz education for many

years. I do, however, see a difference in the community and have noticed an

increase in opportunities to be exposed to jazz.”[19]

That’s because of the additional New Orleans musicians evacuated

there. One of those displaced musicians is jazz educator and avant-garde champion

Kidd Jordan, father of musicians Kent, Marlon, Stephanie, and Rachel. He is

no longer teaching at his longtime post in New Orleans at Southern University,

now lives in Baton Rouge, and has had only one performing engagement in New

Orleans and taught at only one jazz camp there since Katrina.[20]

N.O.

Universities

Universities in the New Orleans area have generally had the benefit

of more substantial financial holdings—plus more storm-dedicated alumni

gifts—than the typical middle- or high-school.

“Loyola University had a slightly smaller freshman class in jazz

studies (and other music majors) but not as small as we had feared,”

summarized John Mahoney, the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Loyola University.

“Tulane is supporting Irvin Mayfield’s New Orleans Jazz Orchestra.

Xavier is coming back under the leadership of Dr. Tim Turner.”[21]

“There

has been an unbelievable amount of devastation. Much of the city is still

in ruins, but jazz music and jazz education are alive and well. There

are many great musicians still living here and a lot of great young students

coming up,” suggested Edward Petersen, Associate Chair and the Coordinator

of Jazz Studies for the Department of Music at the University of New Orleans.

“Jazz education is in a healthier state now than it was before Katrina

because more people recognize not only the cultural value of jazz but also

the economic value. As more people realize that music is one of New Orleans’

and Louisiana’s most valuable exports, the state and private organizations

(especially the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation) are providing a higher

level of support.”[22]

Informal

Jazz Education

Brass

and Street Bands

In my opinion, there aren’t any specific differences

in the culture of learning the jazz tradition informally on the streets now

versus pre-Katrina. Even before the catastrophe left in wake of Katrina, street

musicians had been experiencing resistance from legislation being implemented

by certain city council members, mainly because of complaints from residents

who live in the apartments located near Jackson Square. I believe that now

musicians, particularly ones who don’t play quieter instruments, such

as the acoustic guitar, are forbidden to perform outdoors near the Square.

What happened to the good old days? In spite of it all, fortunately there

are still venues around town, specifically in areas where tourists and locals

would venture, to listen to some good live music....

—Leroy

Jones, trumpeter/composer, Leroy Jones Quintet, Harry

Connick, Jr. Orchestra/Big Band.[23]

The culture of learning the jazz tradition informally on the street

now is completely non-existent! The City Council passed an ordinance post-Katrina

with no community input barring live music on Royal Street (now open to traffic

versus its pre-Katrina pedestrian-mall state) and other French Quarter streets.[24] There is little or no live music in front of St.

Louis Cathedral, and the city-sponsored live brass bands on Decatur Street

near Aunt Sallie’s have not resumed.

I learned to play jazz on Royal Street, in front of St. Louis

Cathedral and playing second-lines. For the most part, these outlets have

been silenced. Even the community second-lines have decreased to almost nothing

due to the city raising permit fees to almost $3,700, much more than the grassroots

Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs can afford. Many musicians have not returned

to New Orleans for this reason as well as the increased cost of living in

New Orleans.

Playing on the street is a sort of bleak scene. Most of the

regular players aren’t living here any more. I used to be able to call

a band and get an answer the same day as to their availability. Now I have

to wait several days while they contact their members in different cities.

When I booked artists for the 2006 Jazz Fest, it cost my budget four times

its usual and took a lot more time to accomplish it.

—Gregory

Davis, Educational Programs Director and Jazz Coordinator,

New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.[25]

The true traditional music of New Orleans jazz is vastly becoming

an “endangered species” in the African American community in which

it was developed and nurtured.

—Joseph

Torregano

Recordings

I received small grants from the Idea Village and from Desire

NOLA. To hell with the SBA (Small Business Association) and FEMA (Federal

Emergency Management Agency). I welcome all the help I can get. I lost hundreds

of thousands of dollars.

—Mark

Samuels, President, Basin Street Records.[26]

Radio

We have lost some of our paid staff; and, most ominously for

a volunteer-operated community radio station, we have lost a substantial number

of our volunteers. Prior to the flood, WWOZ had over 450 people who volunteered

their services in one way or another; [now] WWOZ’s volunteer base is

hovering around 100!

—David

Freedman

Neighborhoods

The availability isn’t close to what it used to be.

You can’t learn the jazz tradition informally on the street when the

street is full of debris and yours is the only family living on the block.

Elder musicians, the educators, are having a particularly hard time relocating

to New Orleans: the scarcity of health-care options and the physical demands

of rebuilding have kept many of them in exile. Fewer churches are functioning

post-Katrina. The flood devastated the family and neighborhood networks that

had fostered the transmission of jazz culture between generations.

—Jordan

Hirsch, Administrator, New Orleans Musicians Hurricane

Relief Fund.[27]

The population with the least economic privilege—including

many musicians—will be much slower to come back.

Until we get tourists back, there is very little work for

musicians.

—John

Shoup, Manager, Dukes of Dixieland.[28]

“The Lion’s Den” took on a lot of water:

eight feet. Rebuilding it is not a priority of ours at this time because we

still don’t have our home in a livable state.

—Irma

Thomas, vocalist, owner of the club “The Lion’s

Den.”[29]

Marching

Band

The words “marching band” bring very different images to

mind to a New Orleanian or Louisianan than to most others; and even in that

region, contrasting genres abound.

The typical image prompted in most of the United States and beyond

might well be of an ensemble that projects the military tradition: lines and

rows as sharply carved as a bed-cover in the barracks, right-angle turns as

crisp as a well-oiled machine, bodies as rigid as a regiment, musical tone-qualities

modeled after a military or concert band, and drum cadences taken directly

from John Philip Sousa. Such bands draw the admiration of many in and out

of the music-education ranks, while others see them as a distraction from

other musical pursuits the students could be learning.

This is simply not the marching band in the majority of New Orleans,

where its look and sound is so greatly influenced by—and carries forward

the tradition of—African music and dance. Its lines and rows flow in

a coordinated but un-militaristic manner. Its right-angle turns convey a dance

step, as does every move of the bandmembers’ bodies. Its tone qualities

are carried down from the brass-band street tradition.

And perhaps most significantly, its drum cadences are most often based

in 3-2 clave, taken directly from the Afro-Cuban traditions of Latin folk

music and jazz. There probably isn’t a well-known melody—pop,

jazz, classical, or folk—that hasn’t been performed and transformed

in New Orleans as a funkier rendition over the legendary streetbeat of that

city. And because of this, not only have the vast majority of school-kids

in The Crescent City over the last century grown up playing music over that

streetbeat, virtually every child and adult

in the city has heard and danced to that sound every Mardi Gras season, live

and via the radio, if not every week during football season’s band halftime

shows, basketball pep band performances, and more. In my opinion and that

of many historians, that streetbeat and its overlay of musical ideas are a

primary reason why so many jazz musicians of all styles have come out of New

Orleans—and why so many genres of music have roots in New Orleans history:

New Orleans has never lost its connection to West Africa.

Before the Civil War, slaves in New Orleans were allowed to congregate on

Sundays in Congo Square (located in what is now Armstrong Park). There they

would drum and dance according to their African traditions. Another institution

that historically provided cultural continuity was our school system—both

public and parochial.

For more than 100 years, our high school marching bands have

long been recognized as some of the most outstanding in the country. How could

they not be—infused as they were with the complex African rhythms filtering

across the generations from Congo Square!...

New Orleans’ cultural identity is its essence. It is

the culture of our people that distinguishes us from any other American city.

In pre-Katrina New Orleans, to be in a marching band was more prized than

to be on the football team....

One of the truthiest truisms for me is that Katrina is an

accelerant for all the trends that were in place before August 2005. The public

school system was already abandoning its unique role as a fundamental carrier

of our cultural traditions.... [Now] each charter school is, in essence, its

own school board, setting its own curricula and making its own business decisions

regarding staffing and allocation of resources.

The bottom line for all charter schools is whether their students

pass standardized LEAP and SASE tests in sufficient numbers to justify the

state renewing their charters to operate. In such an environment...extra-curricula

activities may be seen as just that—“extra”—and easily

abandoned, the better to concentrate all resources on “meat and potato”

courses that assure higher test scores....

How close are we coming to losing the mechanism by which future

generations identify themselves and our city through our unique musical traditions?

Without a future, our heritage may no longer exist as a living tradition—becoming

instead just a postcard for tourists and a commodity for export....

A lot of people outside of New Orleans don’t understand

how important even the school marching band is to jazz education. Sure, marching

can be overdone in the balance of musical instruction. But I wouldn’t

trade my time in the Jesuit High School Marching Band for anything: it was

an introduction to the music and beats that are indigenous to the New Orleans

sound. But now, post-Katrina, entire music programs (much less marching bands)

have been wiped out across the city. There are no places for so many kids

to experience firsthand how to create the streetbeat sound, and the children

displaced to other cities may never experience it again.

—Michael

Rihner

To illustrate the wide-ranging influence

and importance of how the New Orleans marching band tradition has educated

so many students of all cultural backgrounds about the fundamentals of New

Orleans musical style, I often show people a particular video-clip of a New

Orleans Mardi Gras parade. A marching band from a New Orleans suburban, private,

religious-based, all-boys high school makes its way down the street. Suddenly

its two drum majors, one African American and one white, break out into choreographed

dance steps. Seconds later, the entire, mostly white band also dances steps

as it performs its music. Here is freedom from judgment about one’s

motives for dancing, even in a suburban, private, religious-based, all-boys

school marching band: you dance.

Such expression and risk-taking is fundamental

to improvisation and to jazz. The New Orleans marching band style has for

generations been at the root of passing that spirit of exploration to every

resident of the region, no matter the individual’s cultural background.

Housing

|

|

Mold covers the instruments

that had been left behind on high counters by trumpeter Leroy Jones.

Photo credit: Katja

Toivola

|

Jones' music room.

Photo credit: Katja Toivola

|

The affordability of housing (owned or rented) in a given city is a

crucial ingredient for its police, nurses, firefighters, teachers, artists,

and certainly for its jazz musicians. It is here where the fate of Katrina’s

path tore most deeply into New Orleans’ musical heart:

Like most cities across the country, New Orleans already had an affordable

housing shortage before Katrina...and a low homeownership rate: only 47%,

compared to 67% nationally.... African American and low-income families in

New Orleans had far lower rates of homeownership than whites and higher-income

families....[30]

[This] has since erupted into a major crisis...disproportionately borne

by the region’s poorest residents: a full 20% of the 82,000 rental units

that Katrina damaged or destroyed in Louisiana were affordable to extremely

low-income households. The large loss of habitable rental space has caused

sharp rent increases in many damaged areas....[31]

The Brookings Institute [showed that] fair

market rents in New Orleans are now at their highest levels, surpassing pre-Katrina

rent prices: an efficiency apartment that rented for $463 in 2004 now rents

for $725; a one-bedroom that was $531 is now $803.

Despite this severe shortage of affordable housing, of the entire $11.5

billion Community Development Bloc Grant allocation for Louisiana, just $920

million is targeted towards rental housing for extremely low- and very-low-income

people.[32]

Recent

and Future Solutions

The challenges of formal and informal education

and of the very existence of affordable housing have surfaced in New Orleans

on a scale if not unprecedented in the U.S., then certainly unprecedented

for its sudden and sharp increase, as this level of natural disaster is unique

in America. To humanity’s credit, people have stepped forward at every

level to assist, from the single individual to a national effort.

A

Random Sampling

Immediately following Katrina, the Higher Ground Foundation

provided assistance to grassroots organizations such as my New Orleans Jazz

Education Foundation. This allowed me to provide performance and economic

support for local musicians through educational programs. I could send professional

musicians to perform not only in local classrooms but also in classrooms in

other states where evacuees were.

The Jazz Foundation of America has implemented a Jazz/Blues

in the Schools program in several states, all which employ musicians affected

by Katrina and present cultural-enrichment performances in schools throughout

the communities free of charge. And since October 2005 I have traveled as

an independent ambassador of New Orleans music.

The most positive assistance I’ve received post-Katrina

has been from the New Orleans Musicians Clinic and the Arabi Wrecking Krewe.

—Leroy

Jones, trumpeter/composer, Leroy Jones Quintet, Harry

Connick, Jr. Orchestra/Big Band.[33]

Ed Kvet, our Dean of Music and Fine Arts, managed to pay our

invaluable adjunct faculty during the Katrina semester, despite our suspended

operations. One father of a former Summer Camp student sent us a check for

$5,000 to help our program survive! Bloomington North High (IN) sent us the

profits from a Jazz Band Concert they hosted. SUNY Potsdam’s student-run

Madstop Records sent us a share of the profits from a fundraiser they held.

The New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, a non-profit, is dedicated

to providing jazz education to students in this city; and the Tipitina’s

Foundation has done a phenomenal job at putting instruments into the hands

of just about all of the music programs at the high-school level. The Satchmo

Summer Jazz Camp has been around for several years and is also an important

entity.

Two new efforts that have cropped up since the storm are Rhythmic

Roots and Save our Brass. Rhythmic Roots is a community music project presented

by our organization in cooperation with WWOZ radio that invites the community to

an interactive musical experience focused on New Orleans musical traditions.

Save our Brass has partnered some elder statesmen of the brass band tradition

with younger players in an effort to perpetuate the style and rhythms

of the traditional songs.

—D.

Santiago, Backbeat Foundation.[34]

The Contemporary Arts Center has made their performing artists

available to NOCCA free of charge and will do so in the future. The caliber

of the artists has truly been world-class, and they have been inspirational

to our students. These artists include McCoy Tyner, Chico Hamilton, and

Edward Simon. Bonnie Raitt also played at the school and spoke at length to

the students when she was in town for a House of Blues performance and sent

CDs for all 80 of the music students.

We at WWOZ have been blessed through this incredible test,

blessed with support of our radio colleagues: 36 public radio stations sent

us money—unsolicited! The Corporation for Public Broadcasters sent us

money. Louisiana Public Radio, as well. The Development Exchange provided

support. Vendors and consultants...waived fees and continue to work with us

on a pro-bono basis. And of course, our listeners, not just locally but around

the country and the world, came through for us in our Spring Membership Drive,

almost doubling our most successful previous membership campaign.

—David

Freedman

The

Jazz Foundation of America

|

AAt the JFA's "Great

Night in Harlem" at the Apollo Theatre: Jarrett Lillien (President

of E*TRADE Financial), Mrs. Joyce Dinkins (wife of former NYC mayor

David Dinkins), Danny Glover (actor and JFA board member), Agnes Varis,

and Dick Parsons (generous donors).

Photo credit: Jazz Foundation

of America

|

For 17 years the Jazz Foundation of America has been an organization

at the forefront of providing emergency assistance and long-term support to

veteran jazz and blues musicians across the country. “Our small staff

normally handles 500 cases a year,” says Wendy Oxenhorn, the organization’s

tireless Executive Director and advocate. “Since Katrina, we’ve

assisted 1,100 New Orleans emergency cases—plus 600 non-Katrina elderly

musicians in crisis that we would typically serve. We have received active

assistance from such celebrities as Danny Glover, Bill Cosby, Elvis Costello,

Quincy Jones, Bonnie Raitt, and Chevy Chase.” The JFA has focused on

three specific needs: housing, employment, and instruments.[36]

“Days after the flood, because of the ongoing efforts and contributions

of Jarrett Lilien, President of E*Trade Financial, the JFA was able to establish

New Orleans’ first post-Katrina Emergency Housing Fund for musicians:

housing, relocating, and saving hundreds of New Orleans musicians and their

families from homelessness and mortgage foreclosure in nearly 20 states. To

date, the Jazz Foundation has not lost one musician to foreclosure, eviction,

or homelessness. All who came for help were saved.

“Through the beautiful heart of

“Saint Agnes” Varis of Agvar Chemicals, Inc., the Jazz Foundation

created the first performance-employment program, which has grown into an

$800,000 solution. This Agnes Varis Jazz Foundation in the Schools Program

was also made possible with the help of Richard Parsons and the good people

at Time Warner, Inc., actor/producer Fisher Stevens, and the rock band

Pearl Jam. To date, this program has already given 3,100 individual employment

opportunities. It has put several hundred displaced musicians back to work,

with a minimum of $200 per gig, bringing free performances to thousands of

children in schools and the elderly in nursing homes in over eight states

where the musicians have been forced to settle.

|

|

Displaced kids dance

to music provided by displaced artists at JFA Agnes Varis/Jazz Foundation

in the Schools program.

Photo credit: Jazz Foundation

of America

|

“The program is run and coordinated

by the New Orleans musicians themselves. Alvin Batiste, Brice Miller, Davell

Crawford, Jonathan Bloom, Steven Foster, and Bill Summers—all established

educators in New Orleans for many years—are all coordinators of the

program in the various states they have landed. Recording sessions are being

planned to give musicians a CD they can sell to help increase income at club

and festival gigs.

“Through the huge hearts at Music &

Arts Center, Yamaha, and New York’s Beethoven Pianos, the Jazz Foundation

secured over $250,000 worth of new, top-shelf instruments for New Orleans’

most beloved senior and junior jazz and blues artists, including the Treme

Brass Band, Rebirth Brass Band, The Hot 8, Davell Crawford, Shannon Powell,

Dr. Michael White, Fats Domino, Henry Butler, Cyril Neville, Derwin Perkins,

and 95 year-old Lionel Ferbos.

|

JFA Executive Director

Wendy Oxenhorn (center) celebrates delivering new instruments to displaced

musicians, including Red Morgan (sax, sitting), Terrell Battiste (trumpet,

on porch), and James Andrews (trumpet, far right).

Photo credit: Dr. Max

Prince au Schaumburg-Lippe of Salzburg

|

“The Jazz Foundation acknowledges special

thanks and love to all we worked with in this effort. What we cannot do alone,

we can do together: Arabi Wrecking Crew (musicians helping to rebuild

each others’ homes), Baton Rouge Foundation, MusiCares, Derek Gordon

and Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Higher Ground, New

Orleans Musicians’ Clinic, New Orleans Musicians Hurricane Relief Fund,

Tipitina’s Foundation, Actor’s Fund, Society of Singers, Preservation

Hall, and all the others who are working as we are to help keep the musicians

‘afloat.’ We give special thanks to Delta Air Lines for making

a few real miracles possible.”

For years I had heard of Wendy’s round-the-clock efforts to assist

musicians, and now I can report first-hand that she was accessible and on-task

at literally any hour I attempted to reach her. It is no wonder that acclaimed

author and music commentator Nat Hentoff has called Ms. Oxenhorn “the

most determined, resilient, and selfless person I have ever known.”[37]

Her vision for New Orleans’ future is very clear: “If low-income

housing is not created for artists and for the poor, the very garden that

grew this city of music will be at risk of extinction; and New Orleans will

become a cardboard city without a soul.”

The

New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic

Mentioned above, the NOMC is a 501(c)3 non-profit under the Foundation

for the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, co-sponsored by

the Daughters of Charity Services of New Orleans and the New Orleans Jazz

and Heritage Foundation. Its mission is to provide for the health-care needs

of musicians and their families.[38]

“We all know that the unofficial toll of the storm is rising

higher as we suffer the post-Katrina suicides, heart attacks, and strokes

of seemingly healthy friends. Mental health advocates project that 260,000

Louisiana residents will develop post-traumatic stress syndrome.”[39]

French-American

Cultural Exchange

Even if I had never researched it, I would have expected the Jazz Foundation

of America to make heroic efforts in order to assist afflicted New Orleans

musicians: it fits its noble mission. But I was completely surprised to learn

of the level of organized relief assembled in short order by the country of

France, which one might assume would have many other priorities a half a globe

away.

|

Tom McDermott (piano)

and Evan Christopher (clarinet).

Photo credit: Scott

Saltzman (2003)

|

“Our immediate goal was to find means to provide lodging, per

diem, and some work in France for as many musician storm-victims as possible,”

explains Emmanuel Morlet, the Artistic Attaché and Director of the

Music Office of the French Embassy Cultural Services (based in New York City).

“We began raising funds from public and private sources in France and

elsewhere, including from festival promoter George Wein. We recognized that

we could only support individuals, not families; but we did raise sufficient

money to begin the program in January 2006. We started with Paris, which hosted

four musicians: Leah Chase (vocalist), Evan Christopher (clarinet), Tom McDermott

(piano), and David Torkanowsky (piano).[40] Each performed

concerts and gave master classes; and some artists then got additional gigs

from these connections, including from the recording labels we had contacted.

“Our

next avenue was to ask the various Cultural Centers in the Regions of France

(beyond Paris) if they would also be interested in finding a way to host displaced

musicians from Louisiana. Approximately 15 said yes; so we began planning.

Among the musicians hosted was trumpeter Charlie Miller, who visited the Abbey

of Ardennes in Calvados, where he performed at Jazz sous les Pommiers (Jazz

under the Apple Trees).

“The

Embassy also established grants that French festivals could apply for to assist

in bringing Louisiana artists to their venues. Through this program, the eight

members of the Mahogany Brass Band performed multiple times (including at

Festival de Haute Garonne) and presented educational workshops. Twenty-six

musicians performed at Festival de Perigueux, including Greg Stafford and

Evan Christopher. Jimmy Thibodeaux performed at the Festival de Cognac and

the Saulieu Festival. October 2006 brought the Hot Eight Brass Band to Festival

de France Conte.

“All in all, we have some 60 displaced musicians doing residencies.

I have seen many of them arrive in a very weary state, then observed them

virtually brought back to life by these opportunities to perform for, teach,

and interact with the public. We plan to continue this residency plan into

the future.”[41]

Tipitina’s

Foundation

The Tipitina’s Foundation purchased over $250,000 in

instruments from Jupiter Band Instruments, Inc. through the dealer New Orleans

Music Exchange. On the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, $500,000

of new instruments were handed over to the students during the [Instruments

A-Comin’] celebration.... This year the instruments were donated to

the 11 New Orleans schools that will have a functioning music program in the

2006-2007 school year....

The Tipitina’s Foundation raises money for the program each spring

with an annual benefit concert during the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

Jimmy Glickman, owner of the New Orleans Music Exchange, has participated

in the program since it began five years ago and purchases the instruments

following wish-lists provided by the schools. Glickman also donates stands,

drumsticks, and other music accessories to help build the music programs.[42]

“You don’t have a musical culture

unless you’re bringing the younger generation up along the way. For

a whole year, it didn’t happen at all,” outlines Bill Taylor,

a Director of Tipitina’s Foundation. “After the storm, a lot of

instruments were donated. But many didn’t function well and were hard

for us to deal with. The Foundation buys new instruments wholesale locally,

as inexpensively as possible.”

“I really appreciate the work of the New Orleans Musicians’

Clinic and the Preservation Hall Fund, but they assist mostly with professional

musicians. We focus on the students. You need the older ‘legends’

who created the music, the middle-aged musicians who perform it, and the younger

generation to pick it up.”[43]

Sponsors for these efforts included Popeye’s, Starz TV, and Bruce

Springsteen. Tipitina’s Internship Program (T.I.P.) also resumed in

September under the artistic direction of Donald Harrison, Jr.[44] Also starting in

September were weekly Sunday afternoon music workshops, free and open to any

music student.[45]

NARAS

The National Academy of Recording Arts &

Sciences, Inc. (also known as The Recording Academy) is known for the GRAMMY®

Awards but has also created a variety of educational and human-services programs—including

The GRAMMY Foundation® and MusiCares®, both

established in 1989. The GRAMMY Foundation® seeks to cultivate

the understanding, appreciation, and advancement of the contribution of recorded

music to American culture; MusiCares® provides a safety net

of critical assistance for music people in times of need.

By August 2006 the MusiCares® Hurricane Relief

Fund had provided more than $3.5 million in financial assistance for basic

needs to approximately 3,500 individuals directly affected by the disasters.

Longer-term, deeper requirements met have included rent, relocation costs,

and funds for medical care that had been postponed.

MusiCares® is also a lead

partner of “Music Rising,” an initiative that has replaced the

instruments of more than 2,000 displaced musicians located in more than 34

states. The number of musicians affected by the hurricanes is estimated to

be as high as 7,000; each week new clients emerge who need assistance. MusiCares®

was joined by Gibson Guitar, the Guitar Center Music Foundation, U2’s

The Edge, and producer Bob Ezrin in this campaign.

“Grants are still available to New Orleans residents and across

the United States via MusiCares®,” offers David Sears,

Senior Director of Education Programs for the Grammy Foundation.[46] “Donations

are of course not coming in as regularly as they were immediately after Katrina.

We don’t accept musical instruments from the public, as the cost of

fixing them up can be prohibitive. Instead, we use donated funds to purchase

them from wholesalers and retailers.”

The GRAMMY Foundation® initiated

a special grant cycle to archive and preserve recorded sound collections of

the Gulf Coast, announcing in August that $250,000 in grants had been awarded

to 10 recipients, with another $650,000 in funds planned for granting next

year.

The Gibson/Baldwin GRAMMY Jazz EnsemblesSM

program rewards top high school instrumentalists and singers with a week of

music-making, often with GRAMMY Award-winning guest artists. “Because

some of the NOCCA students were displaced, we made extra efforts to locate

them and give them access to auditioning for the Grammy Jazz Ensemble, sometimes

by extending the application deadline a bit.” For example, described

Sears. “One student was not displaced, but his fellow students in the

rhythm section were; so we arranged for professional rhythm players to play

with him on his audition recording.”

The GRAMMY Signature SchoolsSM

program (presented by 7 UP, with assistance from MENC: The National Association

for Music Education) honors top public high school music programs. But it

also recognizes that many schools struggle to maintain any music classes,

much less a full curriculum. So it offers the Enterprise Award for needs-based

applicants. “We certainly hope that affected Gulf Coast schools will

consider applying for that Award,” encourages Sears.

J@LC

Jazz at Lincoln Center announced in February that its Higher Ground

Hurricane Relief Fund, administered through the Baton Rouge Area Foundation,

had awarded 214 grants totaling $2.8 million for musicians and music industry-related

enterprises from the Greater New Orleans area that were affected by Hurricane

Katrina. These funds had been raised from ticket sales to the benefit concert

produced by Jazz at Lincoln Center that had included a live national telethon

on PBS/Live From Lincoln Center on September 17, 2005. Combined with

an online eBay auction, a Blue Note CD, and other independent fundraising

efforts by individuals and organizations all over the world, the event raised

nearly $3 million for the fund. Some of the broad range of donors include

the Jazz All-Stars at New Jersey State Prison; Umbria Jazz Festival, Italy;

Guadalajara Jazz Festival, Mexico; festivals throughout Canada; American and

Canadian Universities, High Schools, and Elementary Schools; Japanese Embassy;

Festival de Jazz de Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain; Rhode Island Hurricane Relief

Festival; Turkish Government; Monterey Jazz Festival, California; Twins Jazz

Club, Washington, DC; and Early Childhood Puppet Theatre, Ltd.[47]

RSOA

The Rebuild the Soul of America (RSOA) Charitable

Trust is an independent, not-for-profit entity with projected assets (as of

September 2006) of $2 million. Among its founding trustees are Wynton Marsalis,

IAJE Executive Director Bill McFarlin, Michael Kazanjian (Kazanjian Bros.,

Inc. and the Kazanjian Foundation), and entertainment veterans Daniel Carlin

(Chair Emeritus of The Recording Academy) and Lisa Marie Hoggs (Celebrate

Jazz! founder). All after-tax profits from ticket sales and related net

profits from TV, DVD, and CD deals from the Rebuild The Soul of America concert

at the New Orleans Arena will benefit the RSOA Charitable Trust.

That August 2006 concert featured Stevie

Wonder; Earth, Wind, & Fire; the Wynton Marsalis Septet; New Orleans Social

Club; Yolanda Adams; Kirk Franklin; Kim Burrell; and Mary Mary. At the same

time, renowned chef Emeril Lagasse and Wynton welcomed back 4,000 children

to New Orleans with a culinary music experience, “Cooking with Music.”

Also announced was the “Ambassador of Swing Talent Search,” in

which Marsalis will search for the best undiscovered jazz talent in the Gulf

Coast region: the thirteen-episode series begins in January.

|

|

Emeril Lagasse cooks

while Wynton Marsalis and friends set the mood for "Cooking with Music."

Photo credit: Hisa Ayano

|

Emeril Lagasse welcomes

students back to school at "Cooking with Music."

Photo credit: Hisa Ayano

|

Why the “Soul of America”? Marsalis had alluded to his

view almost a year earlier, just a month after Katrina. “In the history

of New Orleans lies much of the originality of American culture. Yet, what

investment is our nation making in the arts, in cultivating our understanding

of who we are? ...Unfortunately for us, and more so for our children, cultural

issues in arts education continue to occupy a position of little significance

on the nation’s political agenda. What could possibly be more important

than who you are: your humanity, your soul? ...Because the city of New Orleans

is always discussed in cultural terms, perhaps the rebuilding affords us the

opportunity to raise our social consciousness through a more substantial commitment

to the arts.”[48]

Through the review of grant proposals in the areas of cultural and

integrated arts, the Trust will support projects in New Orleans in the fiscal

years of 2007 and 2008 focusing on four key areas specific to Rebuilding the

Cultural Economy in America: Supporting Civic Life, Informing the Public,

Supporting Musicians, and Supporting Integrated Arts.[49]

Bring

New Orleans Back Commission

Most of the targeted areas for RSOA grant funding are in line with

Wynton Marsalis’ role as the Co-Chairman of the Cultural Committee of

the Mayor’s Bring New Orleans Back Commission, whose other members represent

architecture, artists, the economy, communications, festivals, restaurants,

and local business and civic groups.[50]

The committee’s three-year plan is to “rebuild our talent

pool of artists, cultural groups, and cultural entrepreneurs; support community-based

cultural traditions and repair and develop cultural facilities; market New

Orleans as a world-class cultural capital; teach our arts and cultural traditions

to our young people; and attract new investment from national and international

sources.”[51]

Mindful that money talks, it noted the relatively small amount of money that

Louisiana and New Orleans had invested in 2003 in the “nonprofit cultural

economy of the City”—and the return many times over of that money

to City coffers by the jobs and spending generated. It also detailed the positive

economic effect of the “city’s for-profit creative industries.”[52] But it lamented how low New Orleans’

investment in such creative endeavors was compared to other cities studied.[53]

Armed with the data that “commitment to our future culture is

business in New Orleans,” the Committee intends to pursue every possible

avenue of funding in order to bring the city back—and better. “The

Bring New Orleans Back Commission interviewed more than 1,200 persons and

found that arts education was highly valued by the vast majority of the students,

teachers, and clients,” stated Richard A. Baker, Jr., the Fine Arts

Program Coordinator for the Louisiana Department of Education. “The

population remaining in New Orleans, and scattered, values the arts both as

economic and social influences necessary to make the area a better place to

live.”[54]

New

Orleans Jazz Treasures

The New Orleans Jazz Orchestra (NOJO) recognized

that many of the most important collections of jazz objects were destroyed

or damaged by Katrina. Closed due to damage are The Louisiana State Museum

(housing a jazz collection), the New Orleans Public Library City Archives,

Southern University at New Orleans Center for African and African American

Studies, Dillard University Archives and Special Collections, and Sisters

of the Holy Family Collections.

With the assistance of a grant awarded by The Nathan Cummings Foundation,

NOJO’s New Orleans Jazz Treasures program engages scholars, collectors,

students, musicians, and more in mapping out for posterity the invaluable

cultural wealth generated by the city’s jazz tradition. It will establish

a baseline for what existed before the storm, reveal what remains, and point

to the areas in need of conservation and—where possible—replacement.[55]

Louisiana

Recording

“Louisiana is serious about jump-starting its recording industry,

with an investment-based tax incentive...,” points out George Petersen

of Mix magazine. “Modeled after the highly successful motion-picture

incentives in many states, the music program rebates 10 to 20 percent back

on money spent in the state for production expenses, such as studio fees,

session players, engineers, hotels, catering, media, etc. The minimum expense

to qualify is $15,000 over the course of a year—not necessarily on one

project...as long as the work was done within the state.”[56]

Priorities

The first priority is affordable housing. If there are to

be no teachers or students living in New Orleans, this is a moot question.

Viable residential neighborhoods (Central City, Treme, Seventh Ward) must

be repopulated via rent-subsidies and grants for home repairs.

Beyond affordable housing, funding for music programs in public

schools is crucial. Funding should come from everywhere: public and private.

The city needs affordable housing and jobs to provide the

economic base for the population that has left so that it can return. Music

education has always been under-funded in the public schools. Pay for

decent teachers, instruments, and repaired and updated facilities are all

needed.

The New Orleans Saints receive tens of millions of dollars

from the state. It is an important economic driver for our city. But the music

education of our children (and the education of our children) is more important.

Our city, state, and federal government need to do more to fund these programs.

In order for (Greater) New Orleans to regain its full footing

in jazz education, it’s definitely in need of funding. Education in

general is in need of funding. If the funding is there, the items will be

there. Then we can work on attitude and awareness. If we can get the musicians

and the educators back to the city, that would be a positive start.

I would say to everyone reading this: “If you’d

like to come here and build some affordable housing, please do!”

What is needed most is truthful, sincere, and honest leadership

and advocacy. Support is needed: financial, resource, and mentorship....

When I was hired as Coordinator of Music for New Orleans Public

Schools, I asked about the music budget and was told ZERO. I used my own contacts

and got donations of more than $500,000 of instruments; 1,200 full band uniforms;

and two full sets of K-6 grade music books; plus wrote a music program “blueprint,”

all in my first 60 days! But for the district to provide zero-funding for

more music education: that goes against any possibility of a self-motivated

rebuilding effort. If money is donated to the school district, there is very

little chance it will find its way to music programs.

The crux of the problem is money, cash. Without tourists,

the venues cannot afford to pay a decent rate for the bands. The bands can’t

eat by playing for the door in New Orleans; so they are all on the move trying

to gig outside of New Orleans. The cost of living in New Orleans has increased

significantly, especially for renters.

Jazz instruction is very much private-lesson-driven. New Orleans

had more mentors here than most places did. NOJO is trying to provide support

on an individual basis rather than through large institutions. We say, let’s

give funding to the musicians who can themselves figure out how they

can best work to improve the community. These cultural leaders have done this

for years. Let’s hire this cat and have him go into the schools; he’s

been doing it for thirty years. Let’s fund a way to bring kids together

to play with these mentors who’ve been doing it for decades. This has

to be part of the solution—not only funding large institutions to solve

our jazz-education concerns.

We can’t approach this problem with a formula. Let’s

face it: this is uncharted territory, post-Katrina. And New Orleans is unconventional

to begin with. Jazz is unconventional. New Orleans is used to that.

Early in 2006 Phyllis Landrieu, one of our Public School Board

members, took the initiative to form an ad hoc group calling itself the New

Orleans Music Commission. It consisted of School Board members and staff,

state music education officials, university and high-school professors, and

several representatives of cultural organizations such as the New Orleans

Jazz & Heritage Festival Foundation, Tipitina’s Foundation, and

WWOZ.

After months of intensive work, the Music Curriculum subcommittee,

under the chairmanship of Gary Allen Wood (President/CEO of the New Orleans

Center for the Creative Arts) issued a report: 2010: What Vibrant Music

Programs Will Look Like. The report called for a recommitment to the teaching

of music fundamentals to all our school children.

Among the report’s many recommendations was one that

identified the need for a New Orleans music curriculum.... In my opinion we

need to develop an Advocate-General position for music-in-the-schools with

a view towards assuring the continuity of our New Orleans’ music traditions.

Our effort would not be limited to one school but seek to place music programs

in all schools—public, Catholic, and charter—placing band directors

who are recognized as “tradition-bearers” and implementing a “New

Orleans” music curriculum.

—David

Freedman

Housing

Solutions

|

|

The devastated Lower

Ninth Ward, formerly home to musicians such as Peter Badie.

Photo credit: New Orleans

Area Habitat for Humanity

|

Clearly the affordable-housing challenges are mammoth ones that will

take equally gigantic efforts from many entities in order to solve them. The

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and others

have offered concrete recommendations, such as “preserving existing

federal housing resources by repairing and reopening—rather than demolishing—habitable

public housing and replacing all destroyed units.”[57] And one organization has taken the lead in action

for musicians’ housing.

The

Musicians’ Village

When New Orleans native pianist/singer

Harry Connick, Jr. agreed to be honorary chair of Habitat for Humanity’s

“Operation Home Delivery” to assist the rebuilding effort, jazz

saxophonist and fellow New Orleans native Branford Marsalis agreed to be honorary

chair of the New Orleans Habitat for Humanity efforts. They, and Marsalis

patriarch Ellis Marsalis, have brought heightened visibility to a plan to

restore homes for displaced New Orleans musicians: The Musicians’ Village.

Habitat for Humanity International is a non-profit organization dedicated

to eliminating poverty housing worldwide by building decent, affordable houses

that are sold to those in need at no profit through no-interest loans....

New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity (NOAHH) was founded in 1983 and has

constructed over one hundred homes in the New Orleans Metro area.... The Musicians’

Village, conceived by Harry and Branford, will consist of 81 Habitat-constructed

homes for displaced New Orleans musicians. Its centerpiece will be the Ellis

Marsalis Center for Music, dedicated to the education and development of homeowners

and others who will live nearby.... Construction began in early March, marking

the first large-scale rebuilding plans in New Orleans.[58]

“As of late September, 26 musicians

have been approved for housing in the Musicians’ Village,” updates

Jim Pate, the Executive Director of the New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity,

which serves a five-parish area. “Over 60 more have already cleared

the credit-check process or otherwise advanced significantly. This represents

an upturn in numbers that stems from several primary causes, including assistance

for the musicians by members of ELLA (Entertainment Law Legal Assistance)

and other, pro bono, lawyers.

|

Badie's new home is

now a Habitat House on this block.

Photo credit: New Orleans

Area Habitat for Humanity

|

“I remain confident that the core area

of the Musicians’ Village will be populated 40-50% by musicians and

their families. This area includes 75 single-family homes, the Ellis Marsalis

Center for Music, and the six senior-friendly duplexes. But that’s not

the limit of what we can offer. There are 304 lots in the immediately surrounding

area of the Upper Ninth Ward that are available for purchase by Habitat. This

translates into space for 350-400 more homes. Factoring that in, I will estimate

that some 30% of the overall footprint will be musicians’ homes.

“And if we fill that up, we do not

intend to turn musicians away for lack of space. We are now buying yet more

houses and lots adjacent to this area and also in the Treme community.

“All of these locales have been certified

for rebuilding, and the living area of our houses is built a good two feet

above the newly required height to avoid future flood damage.”

Related

Avenues

“As needed as this home-ownership program

is, it’s only one piece of the puzzle,” offers Pate. “Another

piece took effect in September and will have a major effect within six months:

the Louisiana Recovery Assistance Program offers significant incentives to

rental owners to maintain affordable rates at the lower end of the housing

spectrum, even within higher-level developments.

“Another needed puzzle-piece is to

find a way to bring back the rental owners who used to live in a neighborhood

and then rent out several homes nearby. Such owners are frustrated by the

high cost of building materials and the inordinate time it takes standing

in line to get them. I believe part of the answer may be to establish a ‘building-materials

bank’ along the model of a ‘food bank’: create a co-op of

entities willing to group their buying power together in order to obtain lower

costs.

“Habitat is also meeting with other

organizations to explore the potential of creating two specific kinds of housing

for musicians: ‘gig housing’ and ‘transitional housing.’

The former would parallel the business model of extended-stay hotels. The

transitional home would be a locale where some displaced musicians might be

able to live while working in the city to establish their qualifications as

a Habitat applicant.

“Among the city’s biggest needs

right now is an accelerated distribution of currently blighted properties.

There are some 27,000 such lots in the New Orleans area; and only about 2,500

have been distributed for rebuilding. But now that the LRA buyouts are beginning,

acceleration should occur. Habitat needs those lots. We have the funds to

buy five times the number of houses that we currently have, if we had the

land. It’s important that a significant percentage of new housing be

affordable.”

Lending

a Hand

“The most crucial need for Habitat

right now is volunteers,” states Pate. “The volunteers to date

have been unbelievable, immeasurable, and have as a team accomplished more

than all the governmental entities put together. However, their numbers now

fluctuate greatly, as the post-Katrina rebuilding process is not foremost

in the news these days. I know we can count on a steady stream during summers

and ‘alternative’ spring breaks, when so many college students

come here to assist. But during the rest of the year, the varying numbers

of volunteers of course wreaks havoc on our construction schedules.

“In our five-parish service-area alone,

we could use 1000 more volunteers on any given day, 500 of those in the Musicians’

Village area alone: we could put them all to work. And the Gulf Coast Habitat

affiliates could use another 1000 volunteers each day. So we

welcome all volunteers!”[59]

Why Care?

|

Wynton Marsalis leads

a "second line" for New Orleans returning school children at "Cooking

with Music."

Photo credit: Hiso Ayano

|

By this point in your reading, you have hopefully

found numerous reasons to act. A month after Katrina, Wynton Marsalis spoke

at the National Press Club Luncheon as to why the nation and the world should

care about the future of his hometown:

New Orleans is the most unique of American

cities because it is the only city in the world that created its own full

culture—architecture, music, and festive ceremonies. It’s of singular

importance to the United States of America because it was the original melting

pot with a mixture of Spanish, French, British, West African, and American

people living in the same city. The collision of these cultures created jazz,

and jazz is important because it’s the only art form that embodies the

fundamental principles of American democracy. That’s why it swept the

country and the world, representing the best of the United States....

The city needs to, and the state needs to,

extend its resources to bring the cultural components of New Orleans—the

neighborhood components—back. And also the high-art culture, because

in New Orleans, they both work together.... I played with a funk band; I played

with the Fairview Baptist Church marching band; and I played with the New

Orleans Symphony. That means I could play Beethoven’s music; and I could

play “Oh, It Ain’t My Fault”; and I could play “Tear

the Roof Off the Sucker.” Now that gives you a certain understanding.

And you see very different people in all of those venues; but you see the

same people there, too....

New Orleanians are blues people. We are resilient; so we are sure that

our city will come back. This tragedy, however, provides an opportunity for

the American people to demonstrate to ourselves and to the world that we are

one nation determined to overcome our legacies of injustices based on race

and class. At this time all New Orleanians need the nation to unite in a deafening

crescendo of affirmation to silence that desperate cry that is this disaster.

We’re only as civilized as our level of hospitality. Let’s demonstrate

to the world that what actually makes America the most powerful nation on

earth is not guns, pornography, and material wealth but transcendent and abiding

soul, something perhaps we have lost a grip on, and this catastrophe gives

us a great opportunity to handle up on.[60]

Branford Marsalis served as guest editor

for the September 2006 issue of DownBeat, a special edition largely

dedicated to an exploration of New Orleans roots. I urge you to find a copy

and read it. I spent over half my life in The Crescent City but still learned

a lot from this edition about why the city is so important to jazz—to

music—and why it should be restored.

The post-Katrina exodus of musicians from

New Orleans is surely the largest since Storyville closed in 1917. That exodus

of far fewer musicians some 90 years ago accelerated the spread of jazz nationwide,

and perhaps great musical gifts will come out of this tragedy as well. You

can bet that doctoral theses will still explore the topic a century from now.

But in the meantime, we should do all we can to employ the talents of these

artists, either where they have migrated or by creating opportunities for

them to return to their native home.

A critical process for any rebuilding of the U.S. Gulf Coast post-Katrina

is the full restoration of its arts and cultural sector. The region boasts

one of the richest cultural legacies anywhere, internationally recognized

for its music, literature, cuisine, and dynamic heritage. The rich history

of the Gulf is reflected in the arts and culture of its ethnically and linguistically

diverse population....[61]

The

National Jazz Center

Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco, New Orleans

Mayor C. Ray Nagin, and the Hyatt District Rebirth Advisory Board announced

on May 30, 2006 plans to create a 20-acre performance-arts park that is to

be anchored by a new National Jazz Center. The plans were created by Pritzker

Prize-winning architect Thom Mayne and also call for an outdoor auditorium,

new city government buildings, a new civil courts building, a major redevelopment

of the Hyatt Regency site, and an open-air Jazz Park. The National Jazz Center

will house the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra (NOJO) as well as performance space,

studios, classrooms, a library, and offices.

“The

new National Jazz Center can be a focal point for rebuilding our talent pool

of jazz musicians as well as other artists, cultural troupes, and entrepreneurs

that the Cultural Committee of the Mayor’s Bring New Orleans Back Commission

found to be a critical component of rebuilding the City,” says Wynton

Marsalis. “This project will complement and enhance New Orleans’

vibrant Jazz Culture.”

The Hyatt District Rebirth Advisory Board is composed of leaders in

architecture, urban planning, real estate, economics, business, and the arts

from New Orleans and worldwide and includes Marsalis and Irvin Mayfield, NOJO

Founder and Artistic Director.[62]

“When it comes to rebuilding, the infrastructure

of the National Jazz Center is another approach that works: investors,”

emphasizes Mayfield. “We have people who are invested—financially,

emotionally, civically—in seeing this thing built, regardless of the

demands of the marketplace. Because the bottom has dropped out of the marketplace.

New Orleans is at 50% of what it used to be. But 50% of New Orleans is better

than 100% of a lot of places.

“I’m optimistic about the Center;

but at the end of the day, it’s the economics that will make it happen.

The developers and city are behind it, but a lot of the money has to come

through the federal government and then the state government.”

|

The water-line on the

van demonstrates the intensity of the post-Katrina flood in New Orleans.

Photo credit: Jesuit

High School

|

A

Call to Action: Stay Engaged

“All this stuff is so connected: education,

jazz education, the state of jazz in New Orleans. Any folks who don’t

think they should be engaged in the political process need only take a look

at what’s going on right now,” says Mayfield. “I see millions

of dollars coming in at the state level; but I’m very concerned as to

whether we’re going to see this money come in locally for our needs—a

stated, big portion of which is for education and jazz education.

“People in New Orleans understand that

we’re at risk for losing jazz. The country needs to understand that

this is their music, America’s music. It would be as if Washington,

D.C. burned the original Constitution, saying, ‘We don’t need

this one; we have a lot of copies; we’ve got it in our heads.’

“This is not a small issue about a

bunch of jazz purists who love jazz; no, it’s a lot bigger than that.

Americans have to stay engaged with this challenge. Because believe me, a

lot of funding checks are coming this way—but we need to stay engaged

to ensure that this money is going where we all said it would go. I’m

looking at these federal dollars that are supposedly coming into the State