|

This article is copyright 1990 by Antonio J. García and originally was published in the Music Educators National Conference MENC Journal, Vol. 77, No. 6, February 1991. It is used by permission of the author and, as needed, the publication. Some text variations may occur between the print version and that below. All international rights remain reserved; it is not for further reproduction without written consent. |

Fine-Tuning Your Ensemble's Jazz Style

by Antonio J. García

How can young musicians develop familiarity with the characteristic elements of jazz playing? Antonio García proposes some strategies for directors with limited rehearsal time.

As a frequent adjudicator at festivals who hears as many as fifty ensembles in a given semester, I am struck by the fact that the majority of jazz groups—bands, combos, and choirs—seem to prompt the same advice from adjudicators and clinicians as did the performers on stage before them. This does not necessarily reflect poorly on the state of jazz education; rather, it points out that we are all proceeding along the same path.

Although each ensemble is different, every group is essentially seeking a grasp of the elements of jazz style. Shaping these elements in a tenor fifteen-minute clinic is a challenge; but I have found that certain suggestions seem to bring about positive, dramatic, and permanent changes in an ensemble’s style.

Feel the Beat

It is important that each of your students develops a personal concept of the ensemble’s beat. A group should not depend on the rhythm section for the beat. Your body is a rhythm section: you walk “in two,” and your heart beats “in three.” In order to perform with your best sense of time, you must let some part of your body be physically involved in the beat. Why be stiff? Feeling the beat is one of the joys of music that should not be reserved for the audience.

An ensemble’s sense of time should be developed just as its intonation, phrasing, range, dynamics, and reading are—through practice. For example, pick a medium-swing tempo and have students snap their fingers on beats two and four, Set an electronic metronome on those beats only (that is, when the music is marked as quarter = 120, set the metronome at half-note = 60 on beats two and four). Have group members close their eyes and snap or tap along, imitating a drummer’s sock cymbal. With the metronome running, lower its volume completely for a few bars as the group continues to keep time; then quickly raise it to check the ensemble’s accuracy. Encourage students to move their hands silently on beats one and three to get more physically involved in the beat, and insist that they concentrate. Startling improvements occur, and the students discover how great a good unison ensemble beat feels. (This is often the first moment I see students smile during jazz festival workshops.) And they can practice this, alone or together, without wearing out their “chops.”

Students need not force movement. I do not advocate requiring foot-tapping on specific beats while students play; however, some independently chosen physical involvement is essential to good timekeeping, even if it is as imperceptible as the twitch of a calf muscle.

Softer Isn’t Slower

To develop this time-practice further, pick an ensemble passage that can be played or sung at a variety of tempos and dynamics without straining the students’ upper ranges. Have the ensemble perform the passage at three given tempos (medium, slow, and fast). Have them play or sing each tempo variation twice—first playing loudly, then softly. You must prove to the students that softer does not mean slower and that louder does not equal faster. You can use a metronome to check results. I strongly encourage you to have your group try “scatting” passages, non-pitched but observing the dynamics. When students cannot phrase together vocally, they will realize that the instruments are not the problem. Stress that the softer a passage is played or scatted, the more intensely the time must be felt.1

Unless you desire a special effect, short notes in swing style are “short but fat.” If notes are too short, they have no wind, no vowel, no sound, and no accent (which many short notes require). I use the scat syllable “dit” for short downbeats and “bop” for short upbeats to encourage students to put more body into the note. As the syllables imply, the ends of notes are as important as their beginnings. Give long notes full value, and make certain that the ensemble cuts these notes off together.

Some inexperienced musicians need special help with slow passages. As you slow down any swing passage, all notes become longer—even the short ones. With young bands, I use the metaphor of taking an impression of a comic strip with modeling clay. As you stretch the clay lengthwise, the hero’s face gets wider; so, too, must the notes get “fatter.” Another valuable metaphor is speech itself. Imagine any spoken words slowed down by a variable-speed tape recorder. Observe people who speak slowly: their syllables are longer than those of fast talkers. In the same way, note-lengths must expand at slower tempos or else sound unnaturally clipped and prone to rushing.

Solo/Ensemble Lines

Do your students play swing lines with a dated, “ricky-tick” feel? Swing phrasing uses full-valuedownbeats within eighth-note lines so that the many notes sound like smooth phrases. In contrast, “The Mickey Mouse Song” uses short-value downbeats within lines, hence the term “mickey bands” for a certain historical style of dance music. To emphasize this point to your ensembles, draw a “no mickey” sign on the board: the mouse’s head with the universal symbol of prohibition (a circle and a diagonal line) through it. Then, have students scat phrases to lower their inhibitions and to smooth out their lines—as in a vocal style. Although it is a common perception that swing eighths are like triplets, this is really most true at slower tempos. Listening to professional jazz players, you will notice that the eighth notes even out almost to “classically” straight eighths as tempos quicken; your group will have to do the same.

It is critical that your students have the opportunity to listen to excellent jazz recordings. Without these models, students will have no idea of how to phrase lines within this art form.

Make sure the students remember that the soloist calls the shots on rhythm section feel and dynamics during a solo; the whole ensemble needs to listen to him or her. If players cannot hear the soloist, they are playing too loud—because even if the audience has no difficulty hearing, the players are no longer able to interact. Awareness and communication are vital to jazz; otherwise, the audience might as well observe a soloist playing along with an unresponsive recording.

Staying in Tune

Though I understand the pressures of limited rehearsal or warm-up time. I wince each time I observe a director tuning a group by having each individual play a brief pitch as the director eyes a tuner’s meter and calls out “sharp” or “flat,” then goes on to the next person. First of all, how sharp or flat is the player? I have witnessed countless occasions in which a student’s once-sharp tone is flat on the next pass, sharp again on a third pass, and so on. Perhaps an automotive engine, once tuned by external devices, will stay in tune for a while; but an inexperienced musician will not. We must develop a sense of intonation in our students—or else settle for a future of assembly-line tuning in the ensemble.

Though several tuning methods are useful and worthy of respect, I recommend that ensembles tune a unison/octave A to a piano playing a mid-range A over a D-minor chord. The fifth of a minor chord invites a round tone resembling actual music (which should be the ensemble’s approach to tuning). If you prefer, you can tune the brass to a Bb over an Eb minor chord. I also suggest that you dictate a voicing of the chord that will be used all year to tune each instrumental section further. Either chord can include the ninth and/or the seventh for additional richness. For example, I tune the saxophones’ unison/octave note to the piano first. Once their note is in tune, I cue their chord, wait for it to settle in tune, and add trombone unison notes. Once the trombones are in tune, I add their chord to the saxes’ and add the trumpet unisons. A trumpet chord can then be added. In this way, each section is tuning by ear on the basis of a musical and ensemble sound—not to an unseen mechanical readout.

Finally, I suggest that you ask for a crescendo and decrescendo of the tones or chords to emphasize the need to hold a stable pitch throughout the ensemble’s dynamic range. Most important, if a student is out of tune, ask his or her opinion as to whether the pitch is sharp or flat and by how much. Each year, you will retain some ear-trained veterans, and the time you take to develop their evaluative ears now will save you hours of grief later.

Wind Power

Most young wind players (jazz and classical) use far too little wind in their playing Even soft notes need to “speak,” and this requires sufficient wind. (Wind, meaning moving air, is a preferable term to air, which is often static.) Yet the typical student’s learning process includes a potentially vicious circle. Students aspire each day to their best sound of the previous day and aim their wind and embouchures toward the goal of hearing and feeling the same as yesterday. How, then, are they supposed to arrive at a higher goal when they continue to use their previous approach?

The key to developing a new sound is a new approach for the students: appeal to their sense of sight. Have them blow an airstream at a sheet of paper, then through the mouthpiece at the sheet, then buzzing through the mouthpiece at the paper. Even though the standards for brass and woodwind mouthpiece-buzzing are different, each stage as described yields a visual result. Observe how much wind they move, and insist they do the same through their instruments: a radical improvement in their sound delivery and tone quality often will result. If students are not moving wind out, it is probably because they are not taking it in. See that they take open-mouthed, silent, “O-shaped,” yawning breaths—no hissing of air between clenched teeth. Chances are that they will feel the new sensation of wind movement if they approach it through their sense of sight.

When students first experience this sensation of maximum wind flow, they may think (as I did when I first felt this effect) that they are playing incorrectly: embouchure and lungs respond in an entirely new manner. Teach your students that “different” does not necessarily mean “wrong”: it makes sense that new sounds might require new sensations. Judge the end result by whether you like the sound that results from the new approach. Due in part to childhood asthma and allergies, I was more than twenty years old before I discovered how resonant my instruments were; yet I constantly observe healthy young students who have the same tone-production problems that I had. I have gone so far as to require that students keep a sheet of paper or a large plastic bag in their cases to use briefly each time they take the horn out of the case. This allows them to duplicate quickly and visually on their own the wind movement of the previous day. Achieving such proven results independently saves untold time.2

Vibrato on solo passages in a contemporary ballad style usually is reserved for the end of the longer notes; and even then, it should be minimal. Having students listen to soloists such as vocalists Ella Fitzgerald and Mel Tormé, trumpeter Miles Davis, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and trombonist Carl Fontana will show them that a long and wide vibrato is a lovely effect when reserved for certain special moments. I suggest that you give your ensemble a unison/octave pitch, cue it without vibrato, then with slow vibrato, fast vibrato, back to slow, and finally no vibrato again to expose them to the sensation. An added benefit of this exercise is the concentration it demands: your students’ sound and pitch control in passages without vibrato will also improve.

For Percussionists Only

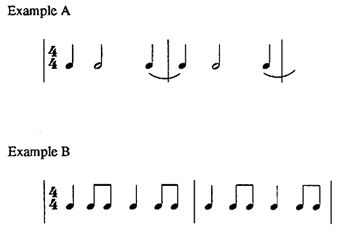

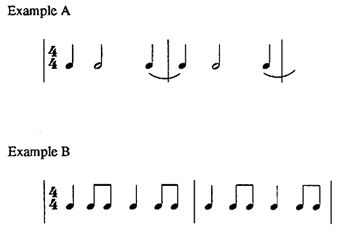

In jazz ensembles, many young drummers strain to play instead of letting the stick do the work it should for them. Have the drummer hold the stick with only the thumb and forefinger and then strike the ride cymbal. The student needs to lower or raise the two-fingered grip until he or she finds the spot that allows the stick to balance, rebounding easily. Help the student gently close the hand around the stick loosely enough to allow the rebounds to continue. At faster tempos, the rebound should provide most of the eighth notes, not the hand or arm! For example, actively playing Example A can yield, with rebounds, the rhythm in Example B:

|

Once you have demonstrated this, have the drummer be creative with the ride pattern. Instead of monotonously repeating the above figure, the drummer should choose where to insert eighth notes amid a steady beat of quarter notes. A player who has to choose a variety of rhythms will listen and concentrate more—and the choosing is part of the joy of drumming.

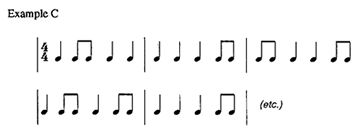

As an exercise, have your drummer play nothing but ride-cymbal quarter notes as the bass provides a “walking” swing line. Insist that the drummer and bassist line up their cymbal and string beats exactly. As eighth notes are added, the quarter notes should remain perfectly aligned. I suggest that you encourage all instrumental and vocal students to experience the feel of striking a cymbal along with a walking bass; it will assist them in their perception of timekeeping. The final ride cymbal feel should include more quarter notes than eighths (see Example C):

|

The foot-driven sock cymbal should generate a tight, crisp “chick” in any swing tune, even at soft volumes. Remember: the softer the dynamic, the more intensely the time must be felt.

Most drummers lacking jazz experience play time and solos with arms rising high into the air as compared to veteran jazz drummers. Have your percussionists watch videotapes of Art Blakey, Louie Bellson, Buddy Rich, Steve Gadd, Steve Houghton, and Ed Thigpen.3 These performers keep their sticks close to the set for a connected, legato, hornlike phrasing. Ask your drummer to play the melody of the chart on his or her set—just the melody; or pick a standard tune like Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing,” and examine the drummer’s stick technique. If you insist that the drummer imitate melodic phrasing, the student will often hold the sticks closer to the drum set without prompting: a new experience for many students. I sometimes compare a jazz drummer to a chef in a well-organized kitchen, whose wrists operate smoothly and deftly, moving and shaking ingredients while he or she remains in an essentially stationary position.

Every soloist (especially in a combo) should receive a different “color” from the drummer, who paints a backdrop for each solo. Have student drummers change occasionally to a different cymbal, a different drum, or drum rims or sock stand, or even lay out (tacet). Encourage flexibility to variations in the rhythmic “groove” or character of the music. This flexibility will allow variations in pace (that is, how frenetic or calm the music may be); but students must always maintain an intense concentration on the passage of the time: the tempo remains the same. In less busy, “spatial” grooves, I compare the flow of time to moving reader-boards such as those at the New York Stock Exchange: the beats go by endlessly regardless of whether they are articulated. One must make sure that each note one does play is a slice from the reader board, a slice that fits exactly into the endless passage of musical time.

If the drummer provides different environments for different soloists, each soloist (and the rest of the rhythm section) will respond differently as well—and your ensemble will not resemble a monotonous parade of soloists. Remember that if you wanted a static accompaniment, your soloists could perform with unresponsive, prefabricated recordings.

Finally, all instruments—but especially the drums—should consider the concert hall or room to be part of the instrument. More than anyone else, a drummer must alter attack and volume to “play the room”; otherwise, the ensemble’s overall balance may be destroyed.

Basics for Bassists

As mentioned, a string bassist’s “walking” beats must line up with the drummer’s ride cymbal—exactly. On an acoustic bass, where the player plucks the strings is crucial for the instrument’s resonance. Generally, near the bottom of the fingerboard seems best.

Be sure your bassist is generating a full sound by plucking the strings without an amplifier. Too many bassists allow the amp to serve as a crutch that makes a nondescript attack sound louder but not better. Once the student is playing firmly, add the amp as needed. Remember, the role of the bass is partly a percussive one.

The final amp setting does not have to make the bass very prominent despite the temptation to emulate recordings that have benefited from carefully controlled acoustics and electronic manipulation If the bass is too loud, the rest of the band will never quiet down enough; but if the bass is nearly acoustic, everyone will play more sensitively because everyone wants to hear that bass line. As an undergraduate, I once mentioned to a visiting-artist drummer that I could not hear the bass as I sat in the far comer of the trombone section. “Can you feel it?” was the response. I replied that I could, indeed, sense the bass pulsing away. “Well, then,” answered the late, great Mel Lewis, “what’s the problem?”

Finally, if you are using a keyboard bass, be sure your keyboardist knows that his or her goal is to emulate the attack, sustain, and feel of a stringed bass—and make sure the student has heard examples of great jazz bassists.

Piano/Vibraphone

Expose your keyboard and mallet players to the Count Basic style of “comping.” They should not feel as though they have to perform every written chord, voicing, or rhythm of the passages unless the groove or “kick” is essential to the piece. As with the drummer, creatively choosing where to play rhythms is part of the joy of accompanying. Less can mean more: make listeners wonder where the next entrance will be. If a pianist or vibist is too hurried to choose, suggest letting a bar or two go by so as to plan the next entrance. They should know that they are part percussion: every note played should line up with the “reader-board” of the time feel.

Naturally, piano and vibraphone players do not have to play simultaneously and constantly. Furthermore, suggest they “comp” in more than just one style: use staccato, legato, block chords, single-note guide-tone lines, pedal points, and more. Remember that these variations erase monotony and elevate the roles of the players and of the ensemble as a whole above that of a machine on autopilot.

Guitar

As student guitarists will discover, many swing tunes require mastery of a “Freddie Green” style. Named for the late veteran Basie guitarist, this style demands that the amp be off (or, if a solid-body guitar must be used, set very low) and the tone be full, rather than a tinny treble. Students need to stroke each quarter note briskly, with a left-hand release of each beat. Players of this style must accent beats two and four slightly and play primarily mid-range voicings low on the fingerboard, producing a husky sound. Not all strings need to be played at all times—less can mean more.

When a stylistic groove does not call for playing in the Freddie Green style, have students perform the written groove and observe the principles for independent placement of chords that you have taught your pianist and vibist.

And Now, Enjoy!

Audience and adjudicator alike can tell when an ensemble enjoys performing. In contrast, it is distressing to watch a group that never smiles. Make sure that you have offered your students a healthy perspective on what is important at a concert, whether it be at your school or at a festival. A wrong note here or there should not be a major concern. Experience the joy of music-making!

Adjudicators can help students maintain this joy. I try to stress the positive points of a performance before offering any constructive comments. I emphasize to the ensemble that, although I may offer a different approach or goal than their director did, neither of us is wrong. A suggestion might have a positive effect on one player but not the next; only by offering as many constructive viewpoints as possible can we increase the odds that something will “click” with a player. Finally, I point out to younger students that just by playing in a jazz group at their age, many of them are experiencing an opportunity I did not have until the latter part of high school. I salute the directors who make such opportunities possible for students in junior high as well as at high school and college levels. Let’s keep the experience an enjoyable one!

End Notes

1 For a discussion of use of scat techniques to improve vocal and instrumental swing phrasing, see Antonio García. “Pedagogical Scat,” Music Educators Journal, Vol. 77, No. 1 (September 1990). 28-34.

2 I am indebted to Arnold Jacobs, former tubist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and to Richard Erb, bass trombonist with the New Orleans Symphony, for their instruction in this regard.

3 Several examples, such as Louie Bellson: TheMusical Drummer, Steve Gadd: In Session, and Ed Thigpen: On Jazz Drumming, are available from DCI Music Video. Inc., 541 Avenue of the Americas, New York. NY 10011 (800-342-4500; in New York. call 2l2-691-l884). These and others may also be available through such distributors as Viewfinder, Inc., PO Box 1665, Evanston, IL 60201 (800-342-3342); in Illinois, call 708-869-0600) and The Jazz Store, 333 Beech Avenue, Garwood, NJ 07027 (20l-233-9529). A number of videodiscs are available from LaserLand, 1685 South Colorado Boulevard, Suite #L, Denver, CO 80222.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Antonio J. García is a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Jazz Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he directed the Jazz Orchestra I; instructed Applied Jazz Trombone, Small Jazz Ensemble, Jazz Pedagogy, Music Industry, and various jazz courses; founded a B.A. Music Business Emphasis (for which he initially served as Coordinator); and directed the Greater Richmond High School Jazz Band. An alumnus of the Eastman School of Music and of Loyola University of the South, he has received commissions for jazz, symphonic, chamber, film, and solo works—instrumental and vocal—including grants from Meet The Composer, The Commission Project, The Thelonious Monk Institute, and regional arts councils. His music has aired internationally and has been performed by such artists as Sheila Jordan, Arturo Sandoval, Jim Pugh, Denis DiBlasio, James Moody, and Nick Brignola. Composition/arrangement honors include IAJE (jazz band), ASCAP (orchestral), and Billboard Magazine (pop songwriting). His works have been published by Kjos Music, Hal Leonard, Kendor Music, Doug Beach Music, ejazzlines, Walrus, UNC Jazz Press, Three-Two Music Publications, Potenza Music, and his own garciamusic.com, with five recorded on CDs by Rob Parton’s JazzTech Big Band (Sea Breeze and ROPA JAZZ). His scores for independent films have screened across the U.S. and in Italy, Macedonia, Uganda, Australia, Colombia, India, Germany, Brazil, Hong Kong, Mexico, Israel, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. He has fundraised $5.5 million in external gift pledges for the VCU Jazz Program, with hundreds of thousands of dollars already in hand.

A Bach/Selmer trombone clinician, Mr. García serves as the jazz clinician for The Conn-Selmer Institute. He has freelanced as trombonist, bass trombonist, or pianist with over 70 nationally renowned artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, George Shearing, Mel Tormé, Doc Severinsen, Louie Bellson, Dave Brubeck, and Phil Collins—and has performed at the Montreux, Nice, North Sea, Pori (Finland), New Orleans, and Chicago Jazz Festivals. He has produced recordings or broadcasts of such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Jim Pugh, Dave Taylor, Susannah McCorkle, Sir Roland Hanna, and the JazzTech Big Band and is the bass trombonist on Phil Collins’ CD “A Hot Night in Paris” (Atlantic) and DVD “Phil Collins: Finally...The First Farewell Tour” (Warner Music). An avid scat-singer, he has performed vocally with jazz bands, jazz choirs, and computer-generated sounds. He is also a member of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (NARAS). A New Orleans native, he also performed there with such local artists as Pete Fountain, Ronnie Kole, Irma Thomas, and Al Hirt.

Mr. García is a Research Faculty member at The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Durban, South Africa) and the Associate Jazz Editor of the International Trombone Association Journal. He has served as a Network Expert (for Improvisation Materials), President’s Advisory Council member, and Editorial Advisory Board member for the Jazz Education Network . His newest book, Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading (Meredith Music), explores avenues for creating structures that correspond to course objectives. His book Cutting the Changes: Jazz Improvisation via Key Centers (Kjos Music) offers musicians of all ages the opportunity to improvise over standard tunes using just their major scales. He is Co-Editor and Contributing Author of Teaching Jazz: A Course of Study (published by NAfME), authored a chapter within Rehearsing The Jazz Band and The Jazzer’s Cookbook (published by Meredith Music), and contributed to Peter Erskine and Dave Black’s The Musician's Lifeline (Alfred). Within the International Association for Jazz Education he served as Editor of the Jazz Education Journal, President of IAJE-IL, International Co-Chair for Curriculum and for Vocal/Instrumental Integration, and Chicago Host Coordinator for the 1997 Conference. He served on the Illinois Coalition for Music Education coordinating committee, worked with the Illinois and Chicago Public Schools to develop standards for multi-cultural music education, and received a curricular grant from the Council for Basic Education. He has also served as Director of IMEA’s All-State Jazz Choir and Combo and of similar ensembles outside of Illinois. He is the only individual to have directed all three genres of Illinois All-State jazz ensembles—combo, vocal jazz choir, and big band—and is the recipient of the Illinois Music Educators Association’s 2001 Distinguished Service Award.

Regarding Jazz Improvisation: Practical Approaches to Grading, Darius Brubeck says, "How one grades turns out to be a contentious philosophical problem with a surprisingly wide spectrum of responses. García has produced a lucidly written, probing, analytical, and ultimately practical resource for professional jazz educators, replete with valuable ideas, advice, and copious references." Jamey Aebersold offers, "This book should be mandatory reading for all graduating music ed students." Janis Stockhouse states, "Groundbreaking. The comprehensive amount of material García has gathered from leaders in jazz education is impressive in itself. Plus, the veteran educator then presents his own synthesis of the material into a method of teaching and evaluating jazz improvisation that is fresh, practical, and inspiring!" And Dr. Ron McCurdy suggests, "This method will aid in the quality of teaching and learning of jazz improvisation worldwide."

About Cutting the Changes, saxophonist David Liebman states, “This book is perfect for the beginning to intermediate improviser who may be daunted by the multitude of chord changes found in most standard material. Here is a path through the technical chord-change jungle.” Says vocalist Sunny Wilkinson, “The concept is simple, the explanation detailed, the rewards immediate. It’s very singer-friendly.” Adds jazz-education legend Jamey Aebersold, “Tony’s wealth of jazz knowledge allows you to understand and apply his concepts without having to know a lot of theory and harmony. Cutting the Changes allows music educators to present jazz improvisation to many students who would normally be scared of trying.”

Of his jazz curricular work, Standard of Excellence states: “Antonio García has developed a series of Scope and Sequence of Instruction charts to provide a structure that will ensure academic integrity in jazz education.” Wynton Marsalis emphasizes: “Eight key categories meet the challenge of teaching what is historically an oral and aural tradition. All are important ingredients in the recipe.” The Chicago Tribune has highlighted García’s “splendid solos...virtuosity and musicianship...ingenious scoring...shrewd arrangements...exotic orchestral colors, witty riffs, and gloriously uninhibited splashes of dissonance...translucent textures and elegant voicing” and cited him as “a nationally noted jazz artist/educator...one of the most prominent young music educators in the country.” Down Beat has recognized his “knowing solo work on trombone” and “first-class writing of special interest.” The Jazz Report has written about the “talented trombonist,” and Cadence noted his “hauntingly lovely” composing as well as CD production “recommended without any qualifications whatsoever.” Phil Collins has said simply, “He can be in my band whenever he wants.” García is also the subject of an extensive interview within Bonanza: Insights and Wisdom from Professional Jazz Trombonists (Advance Music), profiled along with such artists as Bill Watrous, Mike Davis, Bill Reichenbach, Wayne Andre, John Fedchock, Conrad Herwig, Steve Turre, Jim Pugh, and Ed Neumeister.

The Secretary of the Board of The Midwest Clinic and a past Advisory Board member of the Brubeck Institute, Mr. García has adjudicated festivals and presented clinics in Canada, Europe, Australia, The Middle East, and South Africa, including creativity workshops for Motorola, Inc.’s international management executives. The partnership he created between VCU Jazz and the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal merited the 2013 VCU Community Engagement Award for Research. He has served as adjudicator for the International Trombone Association’s Frank Rosolino, Carl Fontana, and Rath Jazz Trombone Scholarship competitions and the Kai Winding Jazz Trombone Ensemble competition and has been asked to serve on Arts Midwest’s “Midwest Jazz Masters” panel and the Virginia Commission for the Arts “Artist Fellowship in Music Composition” panel. He was published within the inaugural edition of Jazz Education in Research and Practice and has been repeatedly published in Down Beat; JAZZed; Jazz Improv; Music, Inc.; The International Musician; The Instrumentalist; and the journals of NAfME, IAJE, ITA, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, Percussive Arts Society, Arts Midwest, Illinois Music Educators Association, and Illinois Association of School Boards. Previous to VCU, he served as Associate Professor and Coordinator of Combos at Northwestern University, where he taught jazz and integrated arts, was Jazz Coordinator for the National High School Music Institute, and for four years directed the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. Formerly the Coordinator of Jazz Studies at Northern Illinois University, he was selected by students and faculty there as the recipient of a 1992 “Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching” award and nominated as its candidate for 1992 CASE “U.S. Professor of the Year” (one of 434 nationwide). He is recipient of the VCU School of the Artsí 2015 Faculty Award of Excellence for his teaching, research, and service and in 2021 was inducted into the Conn-Selmer Institute Hall of Fame. Visit his web site at <www.garciamusic.com>.

If you entered this page via a

search engine and would like to visit more of this site,